This story originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

By now, most readers are likely well aware of the steps taken by British Columbia to shift its recycling strategy. In May 2014, the cost of end-of-life management of residential packaging and printed paper was handed to the businesses that produce these materials. In doing so, British Columbia became the first North American state or province to adopt a full extended producer responsibility (EPR) model for those materials.

A significant component in the province’s move to EPR has been an industry-led effort to update and reconfigure the processing infrastructure through which materials move after they are collected.

As other jurisdictions debate the merits of EPR, it can be helpful to dive into the specifics of how the British Columbia processing transformation has been implemented and the ways a more streamlined approach to post-collection concerns can affect recycling as a whole.

From multiplicity to unity

The province’s EPR move was codified in the Recycling Regulation of British Columbia’s Environmental Management Act (2004), which was amended in 2011 to shift responsibility for end-of-life management of packaging and printed paper (PPP) from governments and their taxpayers to materials producers. Multi-Material BC (MMBC), a nonprofit organization financed by the producers of PPP, was formed to help businesses meet their obligations under the regulation.

MMBC was charged with developing a stewardship strategy, and after more than two years of planning and consultation, MMBC’s Packaging and Printed Paper Stewardship Plan was approved by the British Columbia Ministry of Environment in April 2013. Just over a year later, the amendments to the Regulation came into effect and MMBC’s collection system began operating in communities throughout British Columbia.

MMBC set up the guidelines and expectations for the collection and processing of all residential PPP generated in the province. Collection is the responsibility of municipalities or MMBC directly. MMBC determined that the best opportunity to meet producers’ regulatory requirements for post-collection services was to put forward to the marketplace a competitive request for proposals (RFP).

The primary post-collection services noted in the RFP included the following:

- Pick-up of MMBC designated materials from the 185 depots around the province and transfer of the materials to a designated facility for processing.

- Receipt of all curbside (single-family) and multi-family collected materials at designated receiving facilities for processing or transfer to larger regional processing facilities.

- Processing of all materials into commodities for sale to end market.

- Marketing of all materials to pre-approved end markets.

- Daily reporting of all collection activities to the Canadian Stewardship Services Alliance (CSSA), a national organization that provides management services to MMBC.

- Monthly reporting all marketing activities to CSSA.

Typical of any provincial or state jurisdiction in North America, British Columbia previously had no consistency in regards to its program structure, materials managed or revenue-sharing arrangements. Therefore, the processing infrastructure in place in British Columbia at the time of the release of the RFP in October 2013 was fairly rudimentary and purpose-built to meet the needs of the processing contracts in place in different municipalities.

Under the new MMBC program, all municipalities would be collecting the same materials, which, for all intents and purposes, can be described as all PPP with the exception of multi-laminated packaging and a few other small-quantity materials found in the discarded materials stream, such as low-density polyethylene foam. A full list of materials managed by MMBC can be found at recyclinginbc.ca.

The RFP was structured such that the province of 4.6 million people was divided into 10 zones, providing the opportunity for large and small processors in the province to compete for the post-collection services in any one or combination of zones. Based on the recovery expectations outlined in the RFP, it was clear a major capital investment in new, state-of-the-art recycling equipment would be necessary.

To meet the needs outlined in the RFP, Cascades Recovery Inc., Emterra Environmental and Merlin Plastics decided to form a consortium called Green by Nature EPR (GBN). The three partnering companies together have more than 100 years of experience in recyclables management, and such industry understanding helped GBN quickly recognize that investing large amounts of capital across the numerous material recovery facilities (MRFs) in the province was not the best approach, as it would be too expensive. This economic analysis is based on the fact British Columbia sees relatively small volumes of recyclables annually – about 230,000 tons – and that material is generated across a vast geographic area of over 350,000 square miles (for comparison, Texas is just under 270,000 square miles in size).

GBN determined that the true opportunity lay in restructuring and repurposing the processing infrastructure for the entire province. Based on this proposal, GBN was awarded the province-wide contract, and a new approach to recyclables processing was born.

Repurposing facilities for efficiency

GBN manages all post-collection services, including the movement, processing and marketing of all products collected across the entire province. GBN does not own any of the infrastructure used in managing the materials under the contract – instead, through its process design, the consortium reconfigured most of the existing infrastructure in the province, repurposing it to improve overall processing system efficiency.

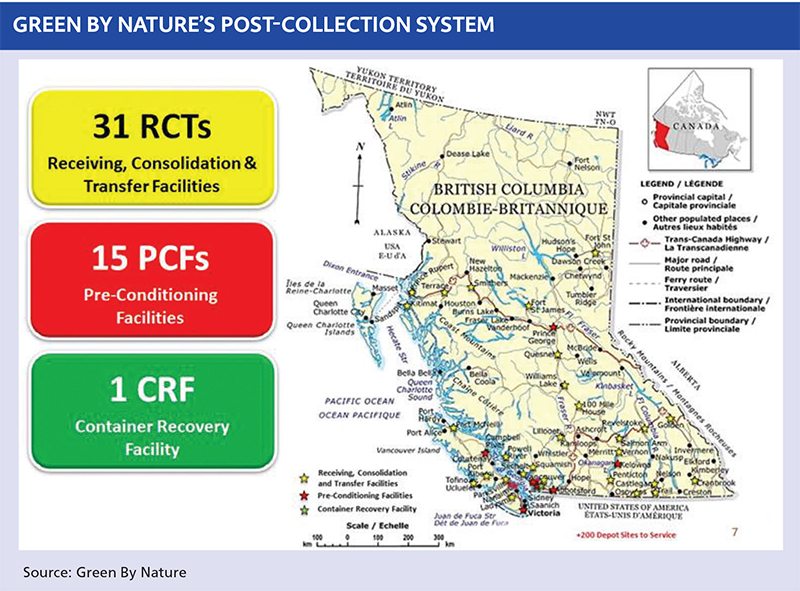

After collection, materials are delivered directly or transferred into a network of facilities owned and operated by numerous recycling companies and municipalities from across the province. Sites known as receiving, consolidation and transfer facilities (RCTs) were added as collection drop-off nodes for bulking. Material is then shipped to pre-conditioning facilities (PCFs) for processing. The PCFs also receive materials directly from the collection source and some manage only specific material types. The MRFs chosen for processing were converted to PCFs. Only one new facility was built – this was the container recovery facility, which will be outlined later in this article.

The collection of materials is all managed through GBN’s logistics department. Materials are collected at depots primarily in megabags (supersacks), although the depots handling higher volumes use balers, rolloffs or compactor boxes for materials.

To ensure the materials collected from depots move as required, a mobile order management system is used. Each unit of material is tagged with a barcode. The collector scans each tag and enters the source and material type. The materials are shipped to RCTs or PCFs where they are received by scanning in the tags and confirming material type. Each unit is weighed and entered into the scanning device. This process allows GBN to precisely monitor the details and movement of each of the 12 different material types tracked in the system. This real-time data on generation and movement allows GBN to maintain an efficient collection network and schedule deliveries of materials for processing in a timely manner.

There are 31 receiving, consolidation and transfer facilities in the province. RCTs receive material from depots and/or the curbside collections serving single-family and multi-family dwellings and aggregate large volumes of PPP material for transport to pre-conditioning facilities and the container recovery facility. It’s important to note the RCTs do no sorting of any materials.

Moving further down the chain, there are 15 pre-conditioning facilities, most of which are repurposed MRFs that receive material directly from depots, curbside systems and RCTs. The PCFs remove all fibers, glass, steel and residues and prepare these materials for shipment to end markets. The remaining stream is what GBN calls PCF mixed containers. These mixed containers, including all plastics, aseptics, polycoated cartons and aluminum cans, are baled and shipped to the container facility for processing.

That container recovery facility is owned by Merlin Plastics, located in the city of New Westminster, just southeast of Vancouver. All containers from RCTs and PCFs are transferred to the CRF for processing. The CRF also receives materials delivered directly from a number of curbside and multi-family programs within 30 minutes of the plant.

The CRF, using state-of-the-art recycling equipment, sorts containers into eight different categories, and once the processing is complete, the materials are sold to end markets. The CRF boasts more than $20 million in new equipment. The facility is capable of managing more than 33,000 tons of mixed containers per year.

Digging into the material mix

Typical of any North American recycling program, the majority of the incoming material handled by the British Columbia system is mixed fiber. However, newspapers are continually shrinking as a percentage of the inbound fiber stream and are expected to all but disappear within 10 years. As such, GBN determined that it made little sense to invest millions of dollars into sorting to capture a newspaper stream.

Meanwhile, for material coming out of single-stream programs where the repurposed pre-conditioning facilities still have a screen for cardboard, the cardboard is recovered when market prices make sense. Otherwise, all fibers recovered in the province are sold as mixed paper. For material coming from dual-stream collection programs, the fibers are not sorted but are instead received and sent straight to baling, saving sorting time and significant cost.

GBN only sells to approved end markets. Chinese markets for mixed plastics, for example, are not approved. The problem of finding an end market for a wide range of plastics was solved by having Merlin Plastics as part of the consortium and by building the container recovery facility. In addition, by focusing on plastics product quality, the approach has ensured guaranteed end market prices for collected material.

Overall, GBN recovers more than 95 percent of all recyclables that enter into the collection network. Through the container facility and its unique design, approximately 97 percent of all rigid plastics that the facility receives are recovered, which is much higher than a typical MRF. Furthermore, the throughput of the entire network is higher because sorting requirements have been reduced. The facilities now focus on making sure high-quality materials leave each plant and that the container facility only has to manage mixed containers, an arrangement that also helps increase throughput.

GBN also works closely with MMBC to find new solutions for new materials. Together, the two entities run pilot projects on specific materials. One of the many benefits of having one organization managing the program and one service provider consolidating the processing side is that system administrators can more effectively and efficiently look at options for the management of the ever-changing stream of PPP. Instead of having to meet with multiple municipalities and multiple service providers, MMBC and its stewards can talk to one body, GBN, to investigate recovery opportunities and then implement strategies quickly and efficiently.

A roadmap toward zero waste

It has been said that the cost of the MMBC program is too high. However, to truly assess the economics and effectiveness of the system, the following should be considered:

- MMBC has 185 depots spread across an area of over 350,000 square miles, including islands in the Pacific Ocean – GBN collects from far-flung locales and moves material to a facility for processing.

- MMBC collects a suite of materials that is much more comprehensive than almost any other program in North America.

- GBN has to move some materials across two mountain ranges, where the roads can be impassible in the winter.

- British Columbia has a deposit-return program for beverage containers, which means there is reduced opportunity to offset costs with revenue from high-

value used beverage containers.

When those factors are taken into account, many people would be surprised at the overall cost-effectiveness of the program in the province. Is this system more efficient than those in jurisdictions that do not use EPR? That question requires an extensive analysis and one which can be challenging to do in a true apples-to-apples fashion. What is clear is that efficiencies in processing currently seen in British Columbia – between reduced sorting requirements, beneficial long-term contracts and economies of scale – are not found in many other programs, regardless of location.

And in many ways, the framework put in place by MMBC and GBN can be seen as initial roadmap toward zero waste.

MMBC designed a consistent and harmonized recycling program. GBN built the processing system accordingly to reflect the consistency of the program across the province. The system is flexible and can readily adapt to any changes that are made to the program. Each facility in the network functions based on its available resources to create an overall system that maximizes recovery rates and the quality of products that are sent to end markets.

In the end, the partners in British Columbia determined how to generate a solution greater in value than the sum of the original parts. GBN provides a low-cost, sensible solution that works, providing a strong recovery environment that is motivated to find positive end-of-life solutions for all PPP.

Daniel Lantz is chief operating officer at Green By Nature EPR and can be contacted at [email protected]. Allen Langdon is managing director at Multi-Material BC and can be contacted at [email protected].