This story originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

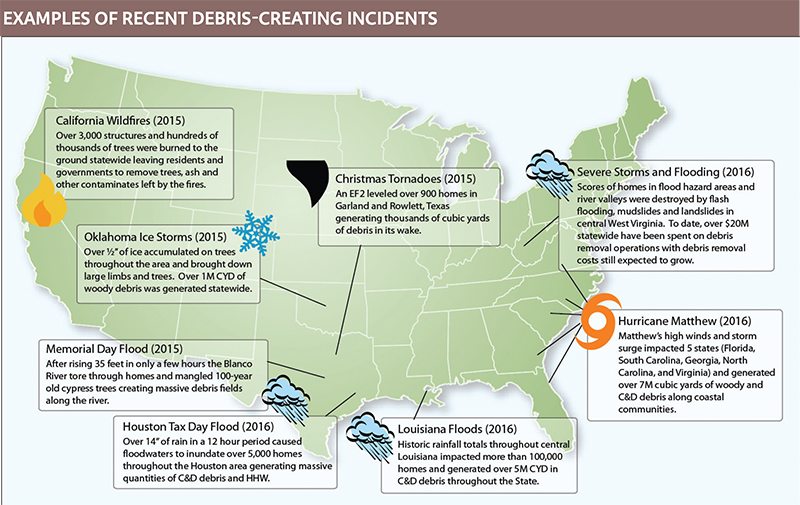

In 2015 and 2016, the United States experienced 86 weather-related major disasters caused by flooding, wildfires, ice storms, snowstorms, tornadoes, severe storms and hurricanes. Disasters of this magnitude are not unique to any one state or region – they can strike any community at any time.

In the aftermath of disasters, communities and local governments face the daunting task of conducting a large-scale debris removal operation. Disaster-generated debris includes trees, household items and even hazardous materials. Severe wind and swift floodwaters can scatter debris throughout the community, affecting public areas and private properties and blocking small streets and major thoroughfares.

For this reason, debris removal represents an enormous cost to impacted communities and the federal government. Between 2000 and 2010, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and local governments spent over $8 billion in disaster-generated debris removal costs.

Sources to help you plan

In an effort to understand and prepare for a debris-generating disaster, many communities have adopted a disaster debris management plan (DDMP). Those that don’t have such a plan in place would be wise to take action to draft one.

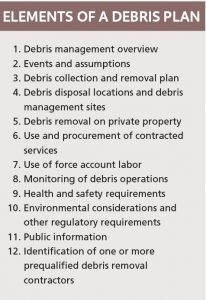

Several resources provide assistance to communities that are looking to develop a plan for disaster debris removal. The FEMA Planning Guide, for instance, describes the planning process, offers strategies to engage local stakeholders and provides guidance that communities need to develop a viable plan. FEMA’s Debris Management Plan Review Job Aid illustrates the critical components that the plan must include in order to be accepted by FEMA and describes the financial incentives for approved plans.

The planning team should begin by setting objectives and goals for the plan, identifying the development team, and describing the plan adoption and approval process. The planning process includes conducting debris estimates, mapping debris management and disposal locations, and developing a strategy and method for debris collection. The plan should also identify priority roads and critical infrastructure components that may be incapacitated in a disaster. It should also designate all roles and responsibilities. Coordination among all departments and agencies is crucial for successful debris operations.

Due to the sheer magnitude of disaster operations, affected communities are often not able to conduct all debris removal operations on their own. Therefore, communities rely on mutual aid from neighboring communities and contractors to conduct much of the work under the supervision of the local government. This involves a procurement process wherein contractors are acquired through competitive evaluations, as required by FEMA and in compliance with federal procurement requirements.

One of the critical services that may be solicited and contracted is debris hauling. Another is called debris monitoring, which consists of oversight and documentation of the entire removal process for FEMA compliance. Communities should identify contractors that are capable of performing debris work of varying size and complexity. The contractors’ qualifications must align with the approved debris management plan. Ideally, contractors should be identified and contracts should be in place on a standby basis long before a disaster is imminent.

Debris management can be a long and complex process due to the severe social and economic impact debris can have on a community. Preparing for debris management is an ongoing process that should be periodically revised and updated with new information.

Debris management can be a long and complex process due to the severe social and economic impact debris can have on a community. Preparing for debris management is an ongoing process that should be periodically revised and updated with new information.

Putting plans into action

In the first few days following a debris-generating disaster, local officials and debris management personnel carry out a number of tasks to begin the removal process with as little delay as possible. Surveys need to be conducted to assess the damage and estimate the amount of debris that has been generated, and critical roads must be cleared to restore mobility. Using ground, aerial and computer modeling, a damage assessment can be conducted to give insight to the estimated volume of trucks needed as well as the duration of pick-up operations. Data collected should be reported to the state for a determination regarding whether federal aid will be available.

Communities will also begin to plan for the second phase of the disaster – the long-term debris mission. It will be important to assess the financial burden of a debris operation, operational requirements, recycling options, and any environmental and historical considerations that may exist.

Throughout this entire process, data must be collected and meticulous records must be kept. Accurate debris documentation is critical for reimbursement, and communities must implement consistent systems to record all financial and time keeping information throughout debris collection.

As debris operations begin, temporary debris management sites (DMS) will be prepared, and truck assignments will begin in order to start the debris removal process. Local officials will meet frequently with their teams, including legal, administrative, and environmental professionals. Meetings also typically take place with federal officials and any debris contractors to discuss strategies, timelines and issues that arise.

Debris that is a result of a disaster may be placed along a public right-of-way, or curbside, for collection. Debris is divided among four categories: vegetative debris (tree limbs, branches or other leafy material); construction and demolition debris (damaged components of buildings); household hazardous waste (paints, stains, solvents); and white goods (refrigerators, air conditioners and other appliances).

Public education is key for operations to run smoothly, and local officials must provide instructions regarding how and where to set out debris for pick-up. Household trash will usually not be collected at this time, and field personnel will not remove debris left on private property unless a special program is implemented.

Legislation addressing cost structure

In January 2013, the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act was signed into law. The Sandy Act implemented legislative changes to FEMA by reducing the cost of federal government assistance and increasing the administrative flexibility of the Public Assistance (PA) Program. These changes also expedite the process of providing and expending assistance and create incentives for applicants to complete projects in a timely and cost-effective manner.

The Sandy Act specifically addresses debris removal assistance and allows for the use of a sliding scale to determine cost share. This means that the federal cost share is increased for debris disposal completed within a specified time frame. For example, debris collected within the first 30 days after the incident will result in an 85 percent federal cost share; debris collected between 31 and 90 days after results in an 80 percent federal cost share; and debris collected between 91 and 180 days after results in a 75 percent cost share. However, there is no federal cost share for debris removal after 180 days.

As communities develop plans for handling materials generated during a disaster, they should identify contractors and partners that will be able to handle projects of varying size and complexity.

The Sandy Act also allows for the use of program income for recycled debris. Prior to this pilot program, if a community decided to recycle its debris and there was some income gained from it in some way, FEMA would deduct this amount from the community’s ultimate reimbursement. This did little to offer incentivizes to communities to explore the recycling or end-use options for disaster debris. Given an overall understanding that it is beneficial to divert disaster debris from landfills when possible, Congress set out to ensure that the Sandy Act would reflect these priorities. While it cannot be claimed as a direct project cost, communities may retain revenue received by recycling eligible disaster-generated debris. Any revenue must be utilized either to pay the local cost share or to fund improvements for future debris-removal operations or planning.

Tangible step toward community recovery

Disaster debris can be among the most costly items for a community to handle after a disaster because it is typically an uninsured loss. In addition, disaster debris has a very visible effect on the community, and clearing debris in a timely manner can have a positive impact on the overall emotional and economic recovery of the region.

A well-designed system of debris management will have pre-established debris management sites and trucking assignments for movement of material.

This is why it is so imperative for local leaders to consider debris management before it is necessary. Having a DDMP in place and having relationships with contractors who can participate in recovery can help ensure compliance with FEMA’s PA Program and ultimately protect a community’s reimbursement for debris management and removal expenses.

John Buri and Anne Cabrera are debris subject matter experts working for project management consultancy Tetra Tech. They have been deployed nationwide on major post-disaster efforts over the past 12 years. In addition to their work on debris removal projects and post-disaster recovery operations, they have both helped numerous clients during implementation of the FEMA Public Assistance program. They can be contacted at [email protected] and [email protected].