This story originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

It is said that nothing is permanent except change, and this is certainly true of the recycling industry. Those of us who have been in the industry for longer than we’d like to admit have witnessed the change from predominantly drop-off recycling programs (if any) to curbside; from multi-material streams to single-stream; from the use of 18-gallon bins to 96-gallon carts. Materials in the waste stream have changed too, and they continue to change. This is now referred to as “the evolving ton.”

While these changes reflect progress, there is still much work to do. Most communities’ recycling rates are below 40 percent. And according to the U.S. EPA, the national average recycling rate is 34.3 percent, and we still dispose of an average of 2.89 pounds per person per day of municipal solid waste (MSW).

Strategies for transformation

The need to mitigate climate change and conserve natural resources requires us to collectively do more. Fundamental transformation that decouples economic health from environmental degradation is needed. Toward that end, two closely related conceptual approaches are being explored and pursued by states, industry organizations, the U.S. EPA and some local governments. These strategies are the circular economy and sustainable materials management. Both are referenced and explored in other features in this issue of Resource Recycling, a fact that highlights their growing importance in industry thinking.

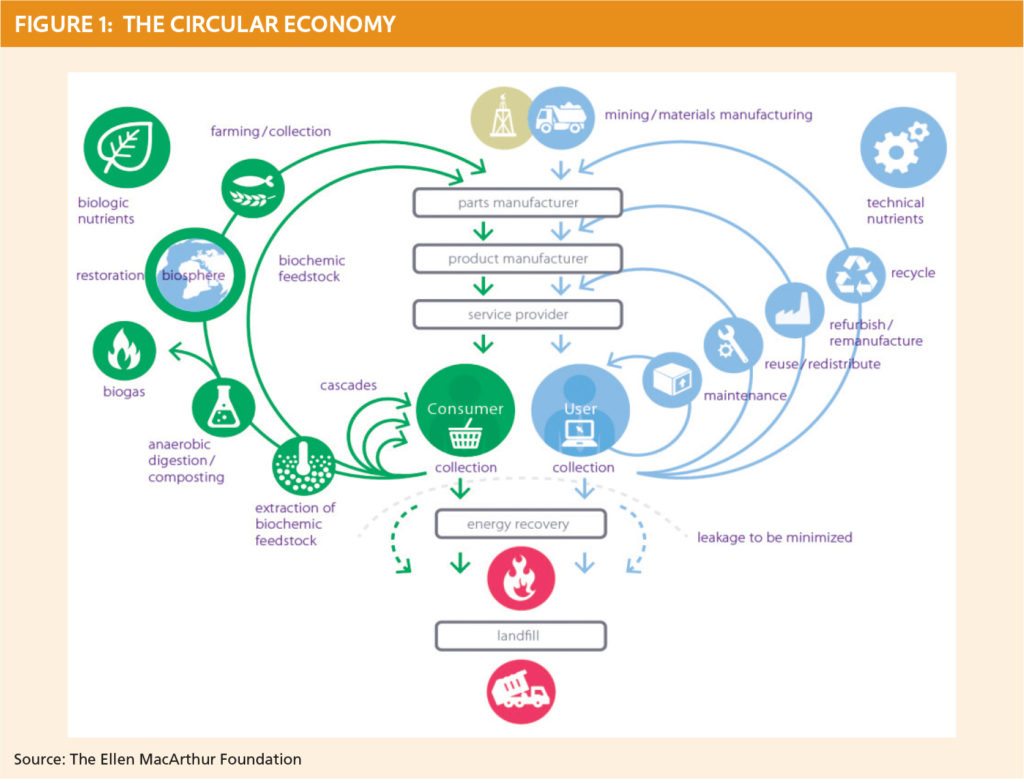

First is the circular economy, which is described by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation as a system that is “restorative and regenerative by design, and which aims to keep products and materials at their highest utility and value at all times.” A circular economy allows for both a sustainable economy and environment – a change from the historic pattern of economic growth resulting in environmental degradation.

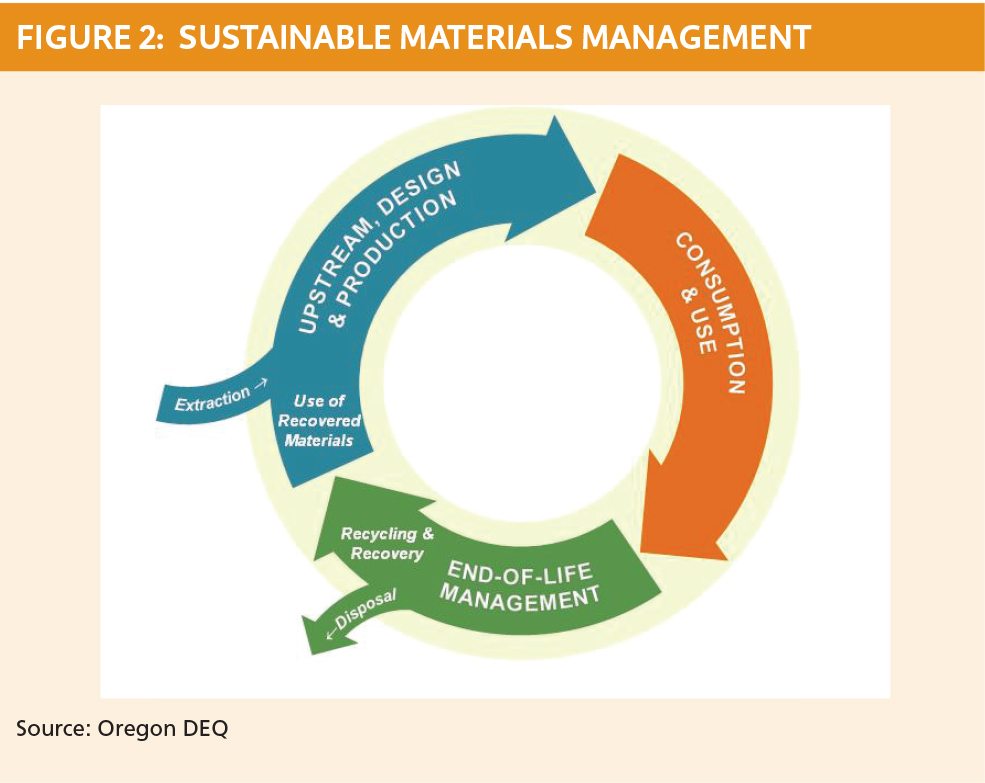

The circular economy is related to sustainable materials management (SMM), a strategy that aims to maximize resource value along the life cycle of materials and differs from current solid waste management strategies that simply seek to minimize waste at the end of life. Under the SMM approach, all stakeholders involved in the life cycle of a product – not just the consumer – have some responsibility in its end-of-life management.

As Figure 1 on page 24 shows, in a circular economy, materials are recovered and directed toward their highest use. There are two cycles – biological and technical – to account for the different types of activities and benefits from these processes. A circular economy preserves and enhances “natural capital,” the world’s supply of renewable and non-renewable natural resources, including plants, animals, air, water, soils and minerals.

Material benefits are restored through maintaining, reusing, remanufacturing and recycling in the technical cycle, which pertains to finite materials. This cycle involves use, not consumption, as most resource value is retained. In the biological cycle, consumption occurs, but resources are mostly restored through natural biochemical processes, such as anaerobic digestion, composting and farming. Resource yields are optimized by circulating products, components and materials at the highest utility at all times in both technical and biological cycles.

What distinguishes SMM from circular economy initiatives is that SMM is typically focused on transitioning from conventional waste management to minimal resource use and maximum resource utility. SMM also considers all environmental impacts at all product stages, including design, material selection, extraction, transport, use and end-of-life management.

Circular economy initiatives, on the other hand, focus on restructuring the economy itself by enhancing resource utilization practices of participating businesses and the systems that support this approach. In order for a circular economy to develop, SMM systems must first be established.

Pushing ahead in the U.S.

Pushing ahead in the U.S.

In an effort to help move toward a circular economy, the National Recycling Coalition (NRC) has acknowledged the importance of SMM and supports its advancement, recognizing that healthy, well-functioning recycling programs are a critical component of SMM and essential to a circular economy.

NRC held an SMM Summit in May 2015 to help recycling industry professionals develop a deeper understanding of their roles in SMM and action steps to implement SMM. NRC is expanding its mission to support “recycling plus,” which includes waste prevention, reuse, anaerobic digestion and composting in addition to recycling.

RSE USA (the U.S. division of consultancy Reclay StewardEdge), on behalf of U.S. EPA Region 4, is developing a vision for SMM and is working with Region 4 states to develop a framework for action to achieve SMM in the region. Those states include Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, South Carolina and Tennessee.

Other initiatives in the U.S. are at early stages, but have some positive momentum.

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), for instance, has developed an SMM Vision and a Framework for Action to achieve that vision. The DEQ has begun rulemaking to support SMM activities and has supported life-cycle analysis research.

In 2012, meanwhile, the City of Phoenix developed a Reimagine Phoenix plan, which includes a vision for turning trash into valuable resources and increasing diversion from the landfill with a goal of 40 percent diversion by 2020. This vision has led to the creation of a project-based collaboration with Arizona State University’s Resource Innovation and Solutions Network (RISN).

RISN has a global network of public and private partners that use collaboration, research, innovation and technology to create economic value to create a sustainable circular economy. RISN is establishing an incubator site to house new processing and manufacturing technologies to support a circular economy. Anticipated outcomes include business creation, job growth, and increased waste aversion, diversion and conversion, along with social and environmental benefits.

Shifts at the local level

Shifts at the local level

In order for today’s current recycling systems to become an effective part of a circular economy, decision-making will increasingly be based on life-cycle assessments. Because all environmental systems and media are considered, materials management professionals will increasingly broaden their focus environmentally and consider a broad array of activities that optimize resource use. In doing so, local government SMM professionals will likely undertake the following types of activities:

- Department restructuring: Traditional “solid waste management programs” will ideally be integrated with departments protecting water and air, as well as other resources, and will likely include “sustainability” in their titles.

Industry collaboration: In supporting the development of a circular economy and SMM, governments have the opportunity to work with processors, manufacturers, researchers, economic agencies and others to advance progress. - Market development: In their role as recycling program managers, local governments can work to enhance recovered materials quality, supporting each material’s highest and best use. State and local governments can implement programs and policies to provide support and incentives (tax exemptions, for example) to businesses seeking to create new or expanded capacity to use recovered materials. Over time, businesses will likely seek to play a greater role in materials recovery, and local governments may be expected to relinquish some management control.

- Policies and programs: State and local governments can collaborate with industry to identify and implement policies that support SMM and the circular economy. Such policies are likely to include those that encourage greater waste diversion and recycling, support optimization of collection and processing infrastructure, harmonize programs, and generate funding to cover costs in areas now under-funded, such as promotion and education.

- Promotion and education: Transitioning to a circular economy requires a paradigm shift that may be initially confusing to system users. Local governments can help educate generators and encourage them to make desired changes in their consumption and use patterns as well as their waste management.

- Research and technical assistance: Measuring life-cycle impacts, a critical component of SMM, is more complex than estimating recycling rates. Local governments will be in a position to encourage and participate in collaborating with state agencies and colleges and universities to obtain and disseminate information regarding life-cycle impacts to facilitate more informed decision-making. Other opportunities for technical assistance might include developing pilot projects for anaerobic digestion or composting and providing guidance to facility operators to enhance operational efficiencies.

- Revised goals and priorities: The traditional metrics of diversion and recycling rates focus on only a small part of the entire product life cycle: end-of-life management. While recycling is an important part of the circular economy, maximizing recycling of all materials is not necessarily the ultimate goal. Instead, recycling is to be maximized only to the extent that the recycling option does not result in other greater environmental impacts (for more information on this paradigm shift, see the May 2016 Resource Recycling article, “Recycling is Just a Piece of the Puzzle,” available at tinyurl.com/RR-Puzzle).

SMM professionals will need to draw from more sophisticated tools to identify ways to capture additional resource value and further reduce negative environmental impacts. This will naturally shift the focus upstream.

Metrics might include those that reflect program efficiency and effectiveness at moving materials to high-value uses. Examples include measuring the portion of recyclables collected sold into market, the percent of households with access to recycling (or other) programs, and participation rates.

The SMM approach provides an exciting opportunity for sustainability professionals to expedite change in many arenas, working holistically and collaboratively with other entities.

Opportunity amid evolution

There is no one universal approach to transitioning to a circular economy. While businesses play a leading role in this evolution, local governments also play a critical role. Local governments have historically held most of the responsibility for providing municipal recycling programs. With the evolving circular economy, they will have the opportunity to collaborate with a broader array of stakeholders than ever before to catalyze innovation, identify sustainable funding, and optimize these systems that are so vital to circular economy success.

It’s true change is the only thing that is constant, but it’s also true that change brings opportunity.

Susan Bush is a senior consultant with RSE USA, a sustainable packaging and product solutions consulting firm serving U.S. clients. Betsy Dorn is director of RSE USA. For more information on RSE USA, go to rse-usa.com.

Pushing ahead in the U.S.

Pushing ahead in the U.S. Shifts at the local level

Shifts at the local level