This article originally appeared in the July 2015 edition of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Recently, we’ve seen many reports of the ruination of recycling due to low oil prices. This is nothing new: A quick Internet search shows recycling’s death has been predicted whenever scrap prices fall.

Prices are now slowly recovering, yet the doom-and-gloom has not abated. Why? Quite simply, the material mix has changed and MRF design has not kept up with the change. MRFs are still predominantly built to separate two-dimensional paper items from three-dimensional bottle and container products.

This existing MRF design served the recycling industry well in the last 10 years. According to EPA data, we recycled 22 million more PET and HDPE bottles, aluminum cans and glass bottles in 2012 than we did in 2005 – that’s an increase of 30.5 percent, in units. Furthermore, we recycled 4,710 tons more cardboard in 2012 than we did in 2005, an increase of 21.3 percent.

Our generation of non-packaging paper dropped by 12,370 tons, or 19.4 percent, between 2005 and 2012, while the recovery rate for that type of material increased from 31 percent to 33.6 percent. It’s worth noting that the significant recycling growth across major material categories happened at a time when per capita waste generation dropped by 8 percent.

So why are we hearing about the demise of recycling? Put simply, a series of factors has driven up the cost to recycle, escalated material loss at MRFs and increased contamination of recyclables, lowering yields.

The heavy effects of lightweighting

Demand for sustainable products and packages ballooned in the last few years. Many brand owners have seen that one of the best ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is to create lighter products and packaging. Such aspirations often mean a switch to plastic or lightweighting existing products: Pouches as well as thinner bottles and containers are examples of this change in the marketplace.

Lightweighting, alongside the noted drop in newspaper readership and printing and writing paper use, sparked a situation where the percentage of paper in the recyclable material mix dropped significantly. MRF operators, of course, observed this change in packaging, and they initially saw profit opportunities. Plastic products have very high scrap values per ton – the second-highest of all traditionally recycled materials (behind only non-ferrous metals) – and markets and demand for most plastic materials have shown continued strength.

Thus, MRFs welcomed the expanded material mix. When scrap prices were high, we all were happy. But the recent downturn of prices for all commodities and the concurrent increase in demand for quality – due in part to China’s Operation Green Fence – revealed that high prices were covering a multitude of sins. To arrive at tonnage and value levels on par with previous years, MRFs must move significantly higher volumes of today’s lightweighted materials through their systems and that typically means significantly higher costs.

Now bring in the traditional 2-D/3-D MRF design noted earlier and you have an even more complex issue. With lightweighting and package changes, the line between 3-D rigid bottles and containers and 2-D paper is very blurry. Think about items like multi-laminate pouches and other modern plastic products. Clearly, multiple forces are wreaking havoc on bottom lines.

Seeing plastic as paper

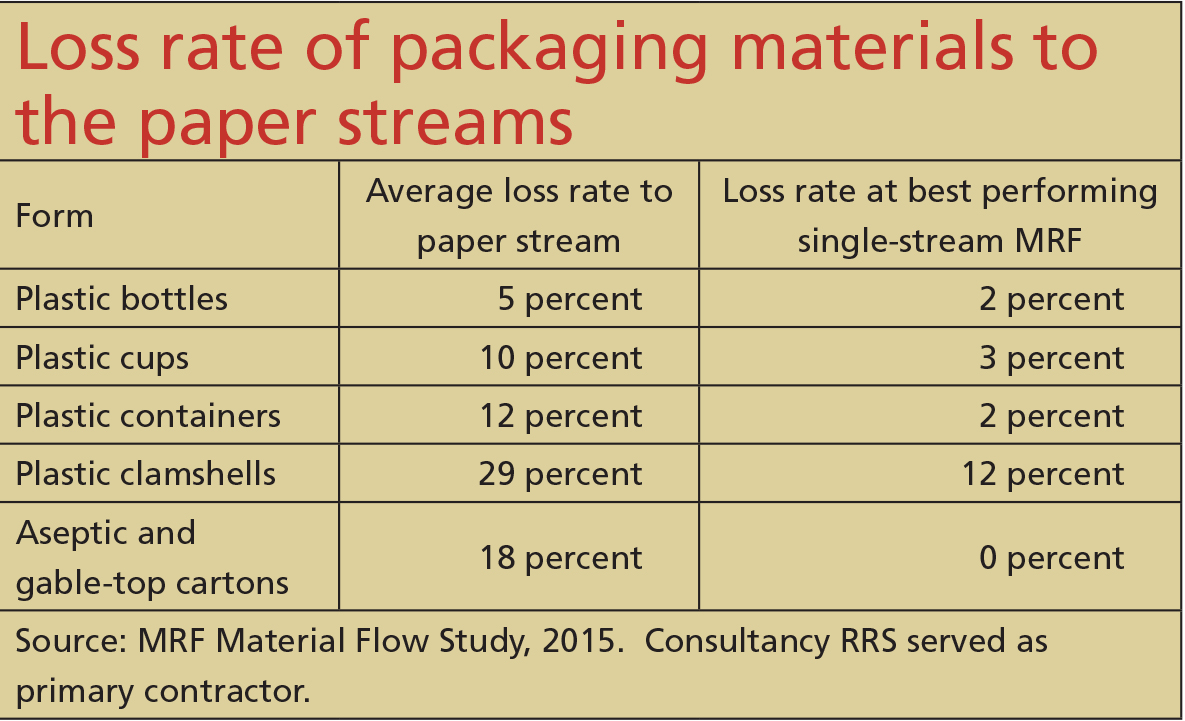

An industry research effort called the MRF Material Flow Study was recently commissioned by the Carton Council, American Chemistry An industry expert explains how commodity prices and material shifts have created a major pinch for MRFs – and details the straightforward path back to profitability. BY PATTY MOORE In My Opinion Reprinted from 26 RR | July 2015 RR | July 2015 27 Council, Association of Postconsumer Plastic Recyclers and the Foodservice Packaging Institute. The study documents that overall loss rates of 3-D containers into the 2-D paper commodities varied from 2 percent to 12 percent, and total material loss – into residue and other commodities – was even greater.

The study notes that “materials that held their shape had a higher tendency to flow to the container line [and be recovered] than those that flattened. Lightweight water bottles had a loss rate of 15 percent.” In short, a number of 3-D products and packages are being treated as 2-D paper in the processing stage. This phenomenon results in two problems: loss of recyclables and increased contamination. Bale quality has dropped, and that’s led scrap reclaimers to push back because they cannot operate profitably with low yields. The industry’s outdated separation technology can no longer be relied upon.

In fact, I believe the most pressing issue in recycling today is the lack of MRF separation technology that reflects the change in our material stream. It’s clear we need significant research and development and capital investment into post-consumer material separation infrastructure that reflects the sustainability-driven product and packaging mix of today and tomorrow.

And as we are developing the technology, we have to address the hard questions around how to structure the costs and benefits of recycling. In other words, who should pay for our materials recovery systems and innovations and who should benefit? What materials make sense to collect curbside? And are there alternatives to curbside collection that are more appropriate for some materials?

Our industry will thrive again

Recycling is expanding: Every year we are collecting and recycling more material types and more volume. Billions of dollars are invested in the capacity to collect, separate, reclaim and use recycled materials in place of virgin products. And the U.S. recycling industry employs millions of people.

Scrap prices will always fluctuate, and the industry can certainly withstand the modern climate. Recycling will thrive again once we upgrade our collection and separation systems with technology that focuses on the changing material mix. No natural system evolves without the re-utilization of resources. There is no waste in nature, and it’s time for our own industry and society to take a page from that ecological playbook.

Patty Moore is president of Moore Recycling Associates Inc., a consulting and business management firm established in 1989. Moore began working in the recycling industry in 1983. She is a fierce advocate of recycling and can be contacted at [email protected].