This story originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of Plastics Recycling Update. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The plastics recycling industry is under pressure to deliver more quality material to end users. As it turns out, key gains could be made just by cutting down on what’s inadvertently lost in the recycling process.

A discrepancy between PET bale yield data and real-world results recently led plastics recycling experts in California to explore how much clean, usable plastic is being improperly rejected alongside actual contaminants.

Quantifying the loss of clean material that’s rejected during the sorting process is the first step to bringing that material back into the reclamation stream. That’s going to be particularly important in the coming years: Brand owners have made major commitments to use more recycled plastic in the near future, creating significantly more demand for recycled PET. This projected demand spike has generated concern that bale supply will fall far short of meeting the need.

The California study, carried out by the Plastic Recycling Corporation of California (PRCC), offers insight into how much good, clean material already in the system is leaking out during PET processing. The work also led to conclusions about how to improve bale yield overall. And most of the insights are applicable to plastic recycling entities everywhere.

Reclaimer numbers don’t jibe with projections

PRCC, a nonprofit voluntary producer responsibility organization established more than 30 years ago, is focused on promoting the reclamation and recycling of PET beverage containers in California. The organization buys and sells recovered PET bottles, moving more than 200 million pounds per year. PRCC handles more than a third of the recovered PET bottles generated in California.

During a meeting between PRCC and the PET reclaimers in California in February 2019, a disconnect emerged between the reclaimers’ bale yield numbers and PRCC’s bale sort data, which the organization regularly generates using samples from materials recovery facilities (MRFs) and other bale suppliers.

Reclaimers said that when they got through processing a typical PET bale, the weight of clear PET successfully sorted was about 65% of the weight of the bale that had come in the door. This was far lower than what PRCC had found in its tests of loads from suppliers.

PRCC committed to researching this gap and, in the months following the meeting, the organization performed a study to better understand PET yield loss. The results underscored that there is more to quantifying bale yield than identifying PET and non-PET materials within a bale.

As a first step, PRCC staff performed PET bale sorts of Grade A bales (the cleanest bales, which include only PET containers covered by California’s container deposit system) and Grade B bales (those containing MRF-sorted PET materials).

PRCC staff used the Association of Plastic Recyclers’ Testing Protocol for Assessing PET Truckload Bale Grades, and workers went through 3,358 pounds of material from 23 suppliers at four reclamation facilities.

The study found that 10.4% of this stream of bales (both A and B grades) was not preferred clear PET bottles. The largest component was green bottles, making up 4.1% of the non-preferred stream. Food residue made up another 2.1%, waste was 1.2%, and smaller fractions came from thermoforms, other colored PET, barriers, aluminum and more.

This finding, suggesting nearly 90% of a PET bale in California is clear PET, was consistent with previous sorts by PRCC.

Why then were reclaimers in the state stating 65% as their typical yield? To answer that question, PRCC took a closer look at the reclaimers’ operations, examining where and how the loss was occurring.

Staff performed sorts on the reclaimers’ whole-bottle rejects, which make up about 15% of total yield loss at reclaimers. These rejects include material that’s cast aside due to contaminating features such as metal or barriers, or due to having little value (colored PET bottles often fall into this second category).

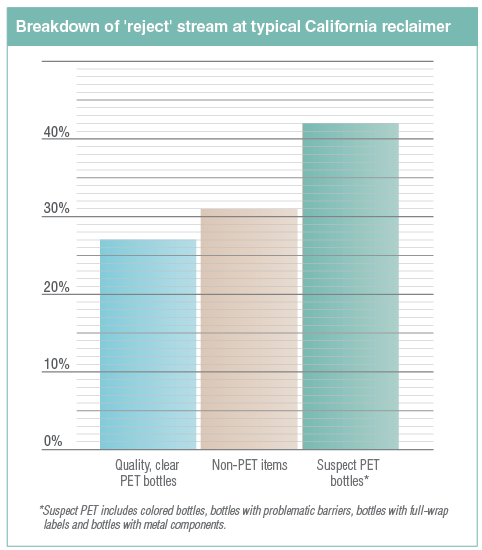

However, PRCC found the the typical reject line at a reclaimer also includes quality materials that are incorrectly rejected – in fact, quality PET made up a significant portion of the reject stream. The analysis found that almost a third (27%) of the bottles removed were good, clear PET bottles pulled with the other problem materials. For comparison, non-PET items made up 31% of the reject stream and suspect PET bottles accounted for 42%.

The suspect PET stream included a variety of different bottle types: colored bottles (30%), juice and other barrier bottles (28%), bottles with full-wrap labels (14%) and bottles with metal (14%). The suspect portion also included PETG, green bottles, dirty bottles and thermoforms.

The study included a few additional tests, including sorting bottles into lightweight and heavy categories, weighing each, removing caps and labels, and washing the bottles.

From these tests, PRCC learned that caps and labels are responsible for 9% of yield loss and bottle residue (dirt and contents) for another 4%. (The study also found that lightweight bottles had a significantly higher percentage of loss from residue and caps and labels, but PRCC does not have enough data to categorize the change.)

Source: PRCC study, 2019

Findings lead to wider analysis and action

To take some action based on the data, PRCC worked with two independent PET recycling engineers, Chuck Jones and Curt Cozart, to first develop a California-specific yield loss analysis by processing stage within a reclamation facility.

The study applied the aforementioned PRCC findings to determine how much PET is lost at each yield loss area. What the study showed was surprising: When good, clear PET is removed alongside unwanted material, bale yield drops as much as 12%.

As a result, the PRCC board of directors has approved several actions, aiming to improve bale yield by reducing this loss.

The organization will collaborate with APR’s “problem container” effort, which allows individuals to report recyclability issues with specific products. “Upon receiving this information, APR works with the container manufacturer to suggest changes to ensure compatibility with the most current recycling technology,” according to the trade association.

PRCC has created new bale grades for Clear-Only and/or CRV-Only PET bales. During the bale analysis, project leaders saw colored PET was one of the areas where a lot of clear PET loss was occurring. That’s because colored PET makes up a high percentage of what’s removed from the bales, so more clear PET escapes with colored PET than with other contaminants.

PRCC asked reclaimers whether adding a clear-only bale would improve their yields, and they felt it would.

There are, however, potential trade-offs associated with segregating clear and colored PET into separate bales. For example, will the improved yield increase the value of the segregated bales enough to support the cost of that increased sortation? And will a colored PET bale be feasible to market, without the more valuable clear PET mixed in to raise its price? PRCC has created the bale grade, and now it’s a matter of talking with bale suppliers to determine whether there’s interest in trying this out.

PRCC also plans to work on legislation for a “disrupter fee” for bottles that are not compliant with the APR design guide. In such a structure, a fee would be charged to manufacturers of generally recyclable products that include recyclability barriers (for instance, a PET bottle with a non-recyclable sleeve). PRCC is still examining what this would look like but is considering an effort to try to get the fee proposal included in recycling legislation that’s on the agenda for the coming legislative session in California.

Informing wider industry solutions

This study was conducted within California to help improve PET bale yields at California reclaimer sites. But in discussions with plastics recycling companies in other states, PRCC learned the numbers from the California test were applicable to operations elsewhere.

The solutions, too, can be expanded on a larger scale. There are three key methods of improving bale yield: legislative, educational, and equipment. It’s going to take a combination of all three to have effective yield increases.

Stakeholders need to challenge equipment manufacturers to look at these numbers and say, “How can we pull out the bad stuff without getting the good, clear PET too?” But these issues must also be tackled from a product design-for-recyclability standpoint, and that incorporates education and legislative efforts.

Patty Moore is the executive director of Plastic Recycling Corporation of California and can be contacted at [email protected].

Colin Staub is the staff writer for Plastics Recycling Update and can be contacted at [email protected].