This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

In late 2017, an article of mine appeared in E-Scrap News describing the anticipated global impact of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

In the article, I predicted the GDPR, which went into effect last year, would have repercussions on companies and organizations far beyond Europe, since GDPR was written to have its protections extended to EU citizens regardless of where they lived or traveled. As I noted then, entities that run afoul of the regulation can lose access to the European market, as well as risk fines of up to 4 percent of their annual revenues.

I also explained that the GDPR would ripple through recycling and ITAD businesses. Because organizations around the world were going to be forced to comply with the new data protection requirements, the recycling and data-management firms on which they rely would be forced to comply as well.

However, it turns out my prediction was wrong. Not wrong on its face, but wrong in that it failed to forecast a far more dramatic impact of the data rules.

Where to many, the GDPR represented some faraway, obscure threat to which they may have to give lip service, it is now obvious that jurisdictions around the world are creating GDPR-like regulations all their own.

In the U.S., California has already passed more stringent requirements, New Jersey has had similar legislation introduced and more states have policies in the works. These regulations are going to be setting the stage for data security standards across the nation in the coming years, and a confluence of market factors is adding pressure for quick action by both governmental and corporate stakeholders.

With the regulatory landscape on the verge of major shifts, data security is primed to become an even bigger business opportunity for electronics recycling operations, if firms can properly position themselves.

Incidents follow action

To fully understand the recent GDPR fallout, it helps to know the European Union was ahead of the curve on privacy protection when in 1995 it passed an earlier policy, the European Data Protection Directive. Countries around the world used the directive as a model for their own data protection strategies.

Not surprisingly, when the GDPR was recently enacted, significantly increasing the requirements and penalties from what was laid out in that 1995 policy, the countries that used the original directive as their model were paying close attention.

Then, as if on cue, came the Cambridge Analytica data collection scandal, in which it was revealed a U.K. political consulting company that worked on the 2016 Donald Trump presidential campaign had discreetly obtained personal information on 87 million Facebook users. News about the company’s practice came out last March, and the ensuing outrage was intense.

More recently, mobile phone carriers and others have been called out for selling personal data without customers knowledge.

More recently, mobile phone carriers and others have been called out for selling personal data without customers knowledge.

In short, GDPR set a new bar for government action around data security, and then high-profile incidents brought privacy risks into the public consciousness in powerful new ways.

It’s also important to note legislative data protection updates across the U.S. were already on a tear as those other trends were unfolding. In the last year alone, 11 states have enhanced their breach notification and/or data protection laws.

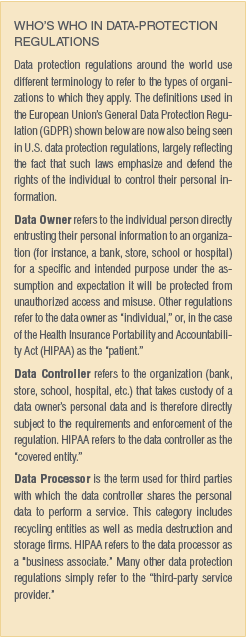

In general, however, those laws are not direct offshoots of the GDPR. They lack the primary tenet of the GDPR model, which gives full control of the personal information to the data owner (see sidebar for more on what we mean by “data owner” and other key terms). On the other hand, these laws do reflect the willingness of lawmakers to embrace data protection, and they helped set the stage for next generation of U.S. data regulations, which are exemplified by California’s Consumer Data Privacy Act (CCPA).

Like the GDPR, the CCPA gives individuals the right to request all personally identifiable information (PII) from any data controller. It also gives individuals the right to amend the information and the right to have any information permanently destroyed if it is no longer needed.

In addition, the CCPA requires data controllers to disclose to the data owner upon request all third-party contractors with which their PII is shared, the criteria used to select such contractors and the contracts in place limiting disclosure and use of PII. Under the CCPA, data controllers and data processors are obligated to protect PII and notify individuals and regulators of any breach.

Finally, perhaps the most significant attribute of the CCPA is the fact it opens the door to class action litigation against data controllers and data processors by removing the requirement for plaintiffs to demonstrate damages beyond the breach itself.

Other states set to follow suit

Despite CCPA’s onerous nature and the powerful opposition it generated, the act passed into law in a matter of months, signed into law last June with a compliance deadline of Jan. 1, 2020. Its swift advance is another sign of the growing appetite for strong consumer protections.

What’s more, California is known as a bellwether on such matters. It is worth remembering that the notion of data breach notification, which is now law in every state and most developed nations, started in California. There is every reason to believe politicians in other states will be looking to extend to their citizens the same protections that are laid out in the CCPA. In fact, the push for similar policies has already begun.

A bill circulating in New Jersey, Assembly Bill 4640, also contains GDPR-like provisions, not only strengthening the state’s breach notification requirements, but granting data owners the litany of rights granted in the CCPA. The New Jersey bill would also require a data controller to provide data owners with information regarding the data processors with which PII is shared – this is very similar to what is described in the CCPA.

The developments in New Jersey also highlight some additional factors that are spurring action in jurisdictions the world over.

Let’s first talk economics. The GDPR restricts PII data-sharing with organizations in countries where similar protections do not exist. Thus, jurisdictions with lower regulatory standards are finding themselves at a competitive disadvantage, with a privacy-based trade barrier now existing between their economies and the economies of Europe. Each country that reacts with stronger policy only adds to the pressure on the others.

In the U.S., states have been forced to take things into their own hands in the absence of federal intervention. Among the reasons for these states to act soon is that doing so gives them an economic advantage over the states without GDPR-type provisions.

Another reason for movement at the state level is the push for influence in the evolving national conversation about data security. While there is no telling when a national data protection law will be adopted in the U.S., chances are good that such a policy will come into effect eventually. State laws passed in the meantime will likely serve as the basis for that federal policy, so state lawmakers realize they wield power on this issue.

Drafters of New Jersey’s 4640 were no doubt intending to establish meaningful consumer safeguards, but at the same time, they knew they were in a position to carve back provisions seen in other policies that some observers argue put an undue burden on data controllers and data processors. Should this legislation pass and should it become a model for federal action, New Jersey-based firms will have an economic leg up because they will already be in compliance and won’t have to make any sweeping changes later on.

The National Association for Information Destruction (NAID) has a 25-year history advocating for strong, balanced data protections in the U.S., and our group is often sought out for advice in the formative stages of such regulations. At present, we count six states where sponsors are preparing to introduce new regulations aligned with the GDPR. And, while economic development and jurisdictional parochialism are the primary drivers, there is an additional consideration on the minds of these policymakers that directly impact electronics recyclers.

Data while you drive … and do everything else

The Tesla Model 3 has a camera mounted above the rearview mirror. GM’s 2018 Cadillac CT6 with Super Cruise driver assistance has one mounted on the steering column. Subaru says it has plans to offer a similar system in its 2019 Forester.

In addition, many new cars now integrate with the mobile devices of drivers, allowing them to download contact lists, log texts, track locations and coordinate information in other ways. Much of this data is transmitted back to the automaker, and a considerable amount of the data stays with the car.

In a GDPR-governed setting, this information would belong to the individual and would require certain data security practices. The car owner (and its other occupants) would have the right to know what information is being uploaded to the cloud or on the machine, as well as the right to review it upon request. They would also have a right to know how it is used and shared, and how it is destroyed. To the extent the PII resides on the vehicle, auto dealerships who take custody of the automobile are either a data controller or a data processor; either way, they would have a legal obligation to protect the data from unauthorized access.

Of course, the world of smart machines collecting PII goes beyond automobiles.

Medical devices, even if they’re disposable, may well store a patient’s identity along with whatever reading is stored. DVRs (and the cable operator serving the content) store viewing habits. An electronic assistant is capable of capturing conversations. Refrigerators now grab images of the food they hold.

According to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, 81 percent of companies polled believe the internet of things (IoT) will be critical to their future success. I have no idea what PII my washing machine may want to know about me, but whatever it is, someday it will be collected.

The number of IoT devices collecting, uploading and storing data only increases the pressure on regulators to confront data protection and privacy.

It doesn’t take any special insight to see what’s coming. Cross-border trade issues, regulatory harmonization, consumer rights, and the IoT are aligning in a way that virtually guarantees a GDPR approach to data protection. Most countries and most, if not all, U.S. states are grappling with this reality or already have something in the pipeline.

Time for e-scrap operators to position themselves

For electronics recyclers navigating this emerging environment, the landscape will hold both opportunity and challenges.

A GDPR-driven regulatory ecosystem will increase pressure on organizations to properly retire all electronic devices. Information protection, an issue already on the radar of many C-suite executives, will become an even more prominent agenda item for corporate leaders. Medium- and small-sized companies and groups that casually ignored data protection in the past will pay keen attention to data protection and disposal.

The simple fact that media will be widely reporting a new round of more severe data protection laws will command the attention of decision-makers and drive demand for data-security services.

And the opportunities for data-management and asset-disposition expertise will extend beyond the existing customer base for these services. Automobile owners, for instance, will need assurances their personal information is not being passed on to the new owner. Whether this erasure is done by a built-in utility or not, the process will need verification.

On the other hand, customers historically willing to accept blind assurances from vendors about data protection will no longer be able to justify such risks. When an individual data owner has the right to request (and receive) information on how data controllers select and contract specific third-party service providers, qualifications take on a new significance. Pressure on data controllers to respond to such requests will lead to more compliance monitoring and service-provider reporting.

In short, e-scrap and ITAD operators and others offering data services will be held to higher standards. And those that prove themselves in the market will see increasing demand.

Like all change, the emerging regulatory shifts will benefit some service providers and cause trouble for others. For those companies ready to embrace the turbulence, they may well be rewarded with unparalleled periods of growth.

Bob Johnson is CEO at the National Association for Information Destruction (NAID), a division of i-SIGMA. He can be reached at [email protected].