Researchers at the University of Glasgow have developed a printed circuit board (PCB) designed to do something most electronics never do: break down safely after doing its job.

The PCBs are not aimed at the phones, laptops and other long-life devices people may picture when they think about electronic waste. Instead, the technology targets a fast-growing category of devices built to be used briefly and discarded, often without any realistic path to recycling.

“People sometimes ask why you would want a biodegradable phone,” said Jonathon Harwell, lead author of a study. “The answer is that you do not. For high-end devices, extending the lifetime and recycling components is far better. This is about the things that are never reused or realistically recycled in the first place.”

Those products include disposable test kits, smart packaging and short-term sensors, Harwell said. He pointed to digital pregnancy tests as a clear example. The electronics inside can be simple, but the product is used once and thrown away, and is ill-suited for recycling systems.

“It’s things where recycling is not practical,” he said of potential applications for the technology.

Conventional PCBs are typically built on fiberglass-resin materials known as FR4, with copper used as the main conductor. The researchers’ paper notes that circuit board assemblies are hard to recycle because they combine many different metallic and nonmetallic materials and because the substrate itself makes up much of the weight while being difficult to process.

The research team’s approach replaces both major elements of a traditional board. The substrate can be made from biodegradable materials including paper, cellulose-based films or biodegradable plastics. The conductor is zinc rather than copper, chosen because it can provide high performance while offering a more biocompatible profile than many other metals.

Harwell said the team initially considered carbon-based materials often used in PCBs, but their conductivity was far below what would be needed to compete with conventional circuit boards. Zinc, he said, was one of the few options that could plausibly deliver the kind of electrical performance modern electronics require.

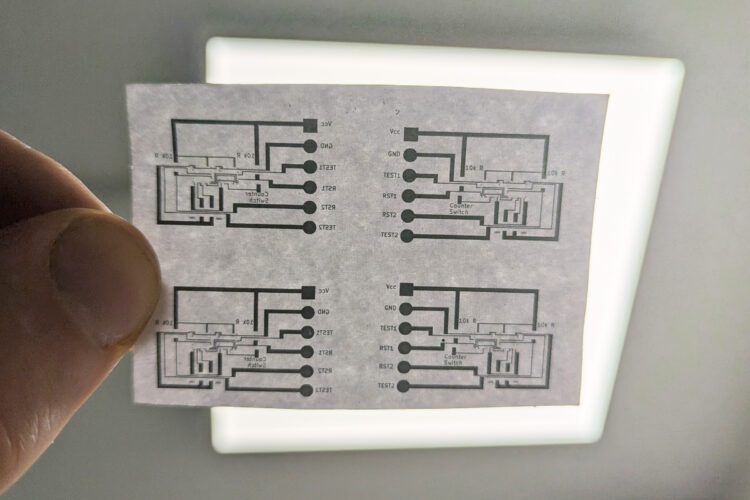

The key challenge was manufacturing. Many biodegradable materials are fragile and typical circuit fabrication processes can be harsh. The Glasgow method starts by electroplating zinc onto a temporary aluminum carrier, patterning it into a circuit layout, then transferring it into a biodegradable substrate while the substrate is processed as a liquid film. The result is metal circuitry embedded in the finished material.

The paper reports the technique can achieve conductive tracks as narrow as 5 micrometers (0.005 millimeters) and a shelf life of more than one year under normal storage conditions. The researchers demonstrated the circuits in several working devices including tactile sensors, LED counters and temperature sensors, and the study describes performance that approaches conventional circuit boards.

The boards are meant to last while they are kept dry, Harwell said, and degrade once exposed to conditions that encourage breakdown.

“If you keep them dry, as far as we can tell, they last for as long as you want,” he said. “But the more you protect them from water, the less biodegradable you make it. That tradeoff is why we’re only aiming for disposable-type products.”

The paper frames the work against the scale of electronic waste, citing global e-waste generation of more than 68.3 million tons in 2024 and noting the difficulty of keeping recycling systems ahead of growing volumes. It also cites European Union estimates that less than 17% of end-of-life printed circuit board assemblies are recycled.

A life cycle assessment included in the paper compared a zinc-based board made with the new method to a conventional fiberglass-copper board of the same size and track layout. The researchers reported a 79% reduction in global warming potential for the zinc-based option, driven by differences in materials and manufacturing as well as end-of-life treatment assumptions.

Harwell noted that biodegradability should not be mistaken for a universal answer to e-waste. For devices meant to last, he said the priority should remain repair, reuse and conventional recycling.

But for items that are effectively destined for the trash, he said, making the circuit board itself safely degradable could reduce the harm caused by disposal, while still keeping performance within what manufacturers expect.