This story originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of E-Scrap News.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

There’s no denying that developments in electronic products have brought immeasurable benefits to consumers. The same cannot be said for electronics recyclers, however. Readers know well it has become increasingly challenging to make money from the material value in scrap electronics.

These developments have had a particularly large impact on the recycling of precious metal-bearing equipment, such as IT and consumer equipment. Because precious metals refiners rely in part on the electronics recycling stream for material, the companies in this segment have kept close watch on the market trends shaping profitability in e-scrap. This refiner perspective is one that leaders in the wider e-scrap industry would be wise to understand.

Refiners, of course, act as key partners for e-scrap processing firms and play an integral role in the e-scrap revenue equation. By understanding the specific needs of refiners and the issues they face day-to-day, e-scrap companies can effectively forge long-term relationships that will help both sides forecast finances, improve efficiency and thrive in the long term.

Recapping market challenges

As the average weight of laptops and other individual product categories has generally declined, so has the material value. This market phenomenon has been fueled by technological improvements at the component level, namely the shrinking of metal structural components and their substitution by plastics.

In addition, miniaturization allows more and more digital tasks to be accomplished on new types of products that are much smaller, and thus less material-intensive, such as tablets and smartwatches. This also leads to device convergence, where, for example, a smartphone is now widely used to replace a digital camera, MP3 player, GPS and other devices, allowing the consumer to theoretically own fewer devices. Small devices are also much easier to dispose of in household waste or to store in a drawer. And the more valuable these products are, the more likely they are to enter reuse rather than recycling streams.

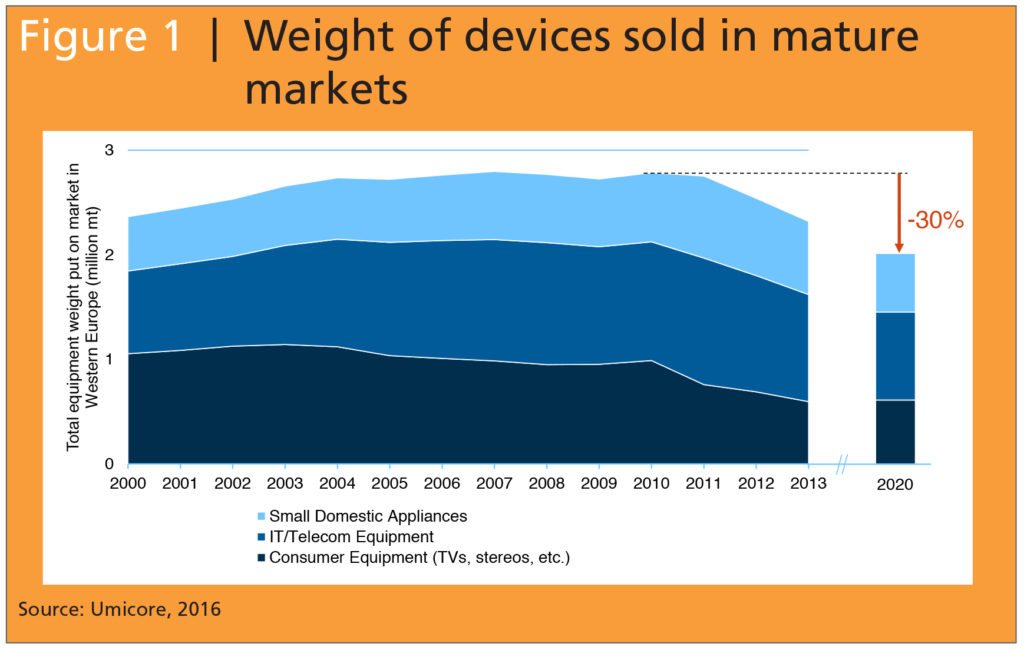

The combined impact of these trends is the reduction in the overall weight of electronic devices sold in mature markets such as the U.S. and Europe (see figure above). According to Umicore’s research, Western Europe will see a roughly 30 percent decline in the overall sales weight of small domestic appliances, IT/telecom equipment and consumer equipment from 2010 to 2020, resulting in less material available for recycling. Western Europe in this instance includes the following nations: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the U.K.

The combined impact of these trends is the reduction in the overall weight of electronic devices sold in mature markets such as the U.S. and Europe (see figure above). According to Umicore’s research, Western Europe will see a roughly 30 percent decline in the overall sales weight of small domestic appliances, IT/telecom equipment and consumer equipment from 2010 to 2020, resulting in less material available for recycling. Western Europe in this instance includes the following nations: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the U.K.

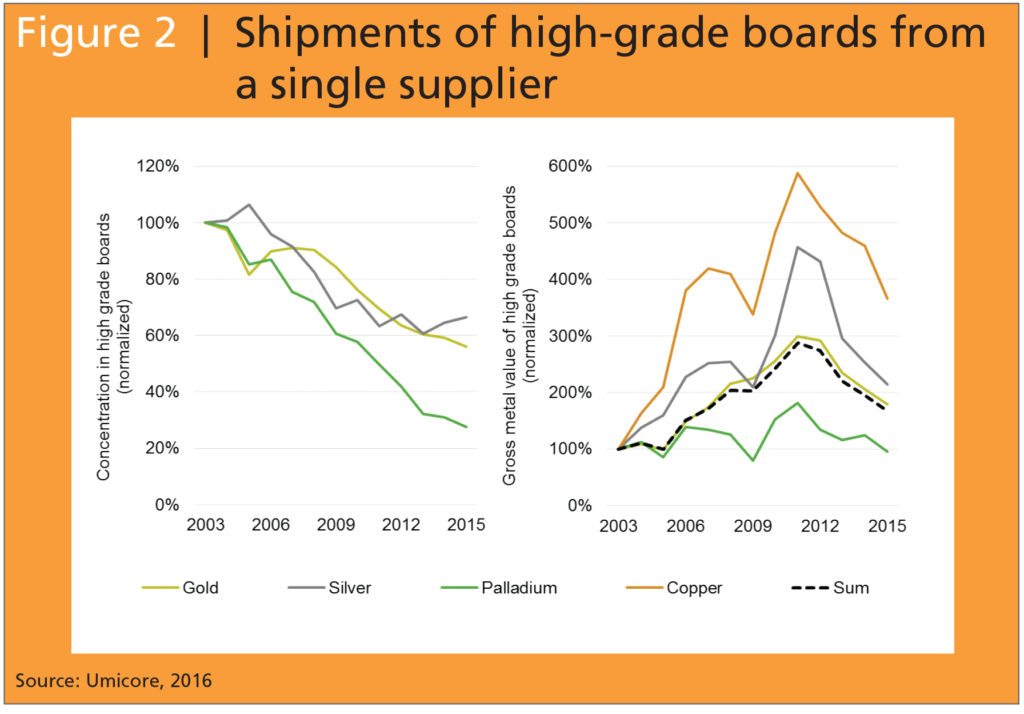

The decline in device weight is compounded by a decline in precious metals in these products. Miniaturization has enabled circuit board weights to decline even faster than device weights. A tablet, for example, weighs 75 percent less than a laptop, but its circuit board weighs 90 percent less than its laptop counterpart. In addition, the precious metal content of circuit boards is declining as manufacturers develop ways to substitute and thrift on precious metals to reduce costs. The impact has been profound. Over the past 12 years, we have seen a 40 percent decline in gold and silver content and a 70 percent decline in palladium content, if we take as an example the shipments of high grade boards from a single supplier (see figure below).

For a while, the impacts of this decline in precious metals content was not really felt in the industry as the rise in precious metal and copper prices more than offset the decline in metal content. The decline in prices since 2011, however, has exposed this painful trend and driven down recycling revenues.

Will higher targets save the day?

Another point to touch on is government policy and the expectation that it could increase e-scrap volumes. The European WEEE Directive, for example, has been an important contributor to the boom in electronics recycling on that continent.

However, while the 2012 recast of the directive adds important measures to drive better recycling performance and improve collection of small devices, it appears unlikely that its higher collection targets will significantly increase overall recycling activity in Western Europe. Recent studies by the United Nations University and others have shown that a parallel, unreported collection system roughly equal in size to the official collection system is operating, mainly through metal scrapyards. While the unreported collection is also recycled, it is unclear if this is done in accordance with high quality standards. Still, the actual collection rate in many Western European countries is estimated at 60 to 70 percent, with the remainder of material mostly going to reuse, export or the waste bin.

However, while the 2012 recast of the directive adds important measures to drive better recycling performance and improve collection of small devices, it appears unlikely that its higher collection targets will significantly increase overall recycling activity in Western Europe. Recent studies by the United Nations University and others have shown that a parallel, unreported collection system roughly equal in size to the official collection system is operating, mainly through metal scrapyards. While the unreported collection is also recycled, it is unclear if this is done in accordance with high quality standards. Still, the actual collection rate in many Western European countries is estimated at 60 to 70 percent, with the remainder of material mostly going to reuse, export or the waste bin.

To meet the new collection targets, it is expected that most efforts will focus on integrating this parallel system into the official system, rather than capturing previously uncollected material.

In addition, the recent “circular economy” trend in Europe and policy proposals coordinated with it are mainly seen by the industry as drivers for more reuse, refurbishment and repair of electronics, rather than immediate recycling. Of course, recycling will always be an integral part of the circular economy, as not everything can be repaired and all reuse products will eventually reach end-of-life and become available for material recovery. However, more reuse, refurbishment and repair will mean longer product lives and, therefore, less material available for recycling per year. In addition, because many of the large reuse markets are outside of Europe and other mature markets, much of the reuse material will be scattered around the world, where collection and recycling infrastructure is not necessarily well developed.

Solidifying links in e-scrap chain

Considering these challenging conditions, it is now more important than ever to critically assess each processing step and create efficient links between the different actors in the recycling chain. In our view, there is still potential for pre-processors of e-scrap to link more efficiently with end processors of copper and precious metal scrap fractions. A greater understanding of the capabilities of modern end processors can help in this regard.

Most of the formal end-processing of copper and precious metal scrap fractions is done by integrated smelter-refiners, such as Umicore. These operations employ best available technologies at significant economies of scale and treat a mixed feed of materials, which enables them to adapt to the changing availability of e-scrap. They must also be able to adapt to the trends discussed above: declining circuit board weight, declining precious metal content and volatile metal prices. At Umicore, end-processing means high precious metal recovery rates, recovery of 17 metals in total, high environmental performance and responsible solutions for all contained elements, including those that are harmful.

E-scrap materials with a wide range of composition and physical aspects can be treated by end processors. These materials may come out of both dismantling and shredding processes and include but are not limited to:

- Whole and shredded printed circuit boards

- Other electronic components (pins, connectors, chips, relays, etc.)

- Mobile/smartphones and other small IT devices with large batteries removed

- Mixed shredded/sorted materials containing circuit boards, plastics, metals and other materials.

In general, the preparation of materials for end-processing should be limited. This approach avoids precious metal losses, which can be significant in intensive separation processes such as shredding, especially when these processes are not fine-tuned for the specific material being treated. Intensive processes still play an important role in the recycling chain, however, and can provide a better return in some cases, depending on equipment type, quantity, quality, metal prices, recovery efficiency and labor cost. Materials that typically require additional processing before they can be accepted by end

processors include printed circuit boards with large metallic pieces, power cords and cables, hard disk drives, and laptops and other devices with large screens.

While additional processing for removal of large iron or aluminum pieces may be required, additional removal of plastics is typically not required, as they are used as an energy source in smelting and therefore reduce the use of fossil fuels.

Working together with a refiner

There are several important points to consider when evaluating working directly with an end processor and maintaining strong relationships in this realm. As most end processors work at large economies of scale – with more than 10,000 metric tons of e-scrap materials treated annually – they typically have a minimum quantity of material required to initiate business.

For companies that are able to supply this amount of material, it is normally advantageous to work directly, rather than through a trader. In order to provide a quote, an end processor will normally need to know the type of material and get a rough idea of the composition – photographs can be helpful here – as well as the quantity available.

It’s also critical to understand that end processors work on assay-based financial settlement, meaning they will analyze the material once it arrives to determine metal content. This metal value, or physical metal, is then paid back to the supplier, minus refining charges and deductions. Getting paid based on the actual measured value of the material may be slower, but the process is more reliable and typically provides a better return than what is garnered through telquel, or fixed-price, buyers because fixed-price operators need to ensure a high safety margin and must themselves contract with end processors.

In addition, receiving the full analysis of your material can help you assess the performance of your process over time and spot trends in the composition of the e-scrap stream you are receiving.

When working with assay-based settlement, it is important to choose an experienced and trustworthy partner. The assay result is both critical to the financial settlement and challenging to get right for highly heterogeneous materials such as e-scrap. Small errors or manipulations in precious metal contents can have large financial impacts. Therefore, look for a partner with reliable systems to:

- Conduct advanced sampling methods for heterogeneous materials

- Collect any dusts that are created in the sampling procedure and add them to the final result

- Conduct double-blind laboratory analyses

- Reduce the risk of human error through automation

- Prevent cross-contamination between materials

- Prevent the mix-up or loss of samples.

Benefits of a level playing field

Fortunately, the selection of a good end-processing partner is now easier thanks to the EERA/Eurometaux general standard on WEEE end-processing, to which companies have had the opportunity to be certified since 2014. This standard complements other electronics recycling standards covering different parts of the chain aiming to increase overall recycling performance and create a more level playing field.

Umicore firmly believes that by leveling the global playing field and building more efficient links between actors in the chain, the industry will adapt and overcome the challenging trends seen today.

Thierry Van Kerckhoven is the global sales manager of refining services recyclables at Belgium-based Umicore Precious Metals Refining NV, where he has worked since 1999. He leads an 11-person team responsible for the global sourcing of e-scrap, spent automotive catalysts and other recyclable materials. He can be reached at [email protected].