This story originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of E-Scrap News.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Closed Loop Refining and Recovery was founded in 2010 with a straightforward business plan. The company would address the growing need for a domestic CRT glass recycling process by introducing a technological solution.

At the time, U.S. sales of new CRT TVs and monitors had dried up and the heavy, low-value devices were flooding the recycling and disposal stream. Closed Loop’s leaders wanted to design and build a furnace capable of processing around 72 million pounds of CRT glass a year, a feat that would easily make it one of the largest CRT glass recycling operations in the country.

Laying down roots in Phoenix in 2010 and Columbus, Ohio in 2012, Closed Loop quickly began accepting CRTs from a wide array of sources, including state electronics recycling programs funded by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), independent recycling companies and the federal government.

The goal, according to the company, was to amass enough material to properly feed its future furnace, even if it meant letting CRT inventories in Arizona and Ohio balloon, flouting federal management regulations in the process.

“The landlords were well aware, and so were the customers and the OEMs that allowed shipment to our site, of what we were doing,” Closed Loop’s Brent Benham said in an interview with E-Scrap News this spring.

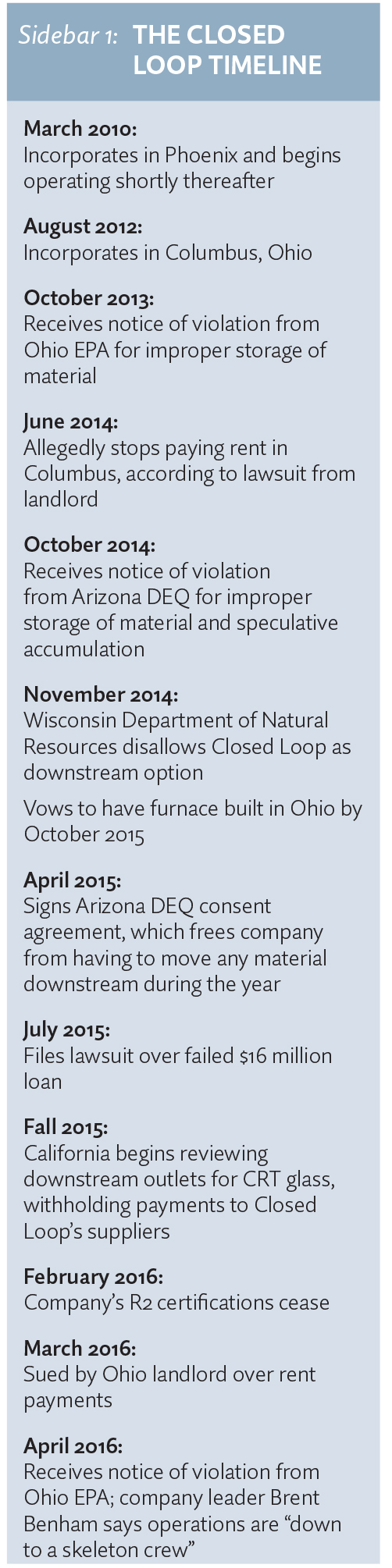

But after vowing for six years to construct a furnace and hitting a number of public snags (see Sidebar 1 below for a detailed timeline), Closed Loop’s technological breakthrough never materialized. The business is now hanging on by a thread, and millions of pounds of CRT glass sit at its sites.

Interviews with Benham as well as with government regulators, OEM representatives and other industry stakeholders shed light on the company’s struggles and the uncertain fate of the largest stockpile of CRT material this country has ever seen.

A company unravels

In April, Benham acknowledged in an interview with E-Scrap News that Closed Loop was “down to a skeleton crew.” The company had received a notice of violation from the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and was behind on its leases in both Arizona and Ohio. Benham would not say how many employees remained at the company, but blamed the current market climate, along with a handful of other factors, for the company’s descent.

Robert Cruz, Closed Loop’s longtime plant manager, had just stepped down from his position at the firm. Co-founder and part owner David Cauchi, who declined to be interviewed for this article, also left the company to join startup Arrow Technology Corporation. (The company has no affiliation with the larger industry company Arrow Electronics.) Beyond Benham, it is unclear if any employees now remain with closed loop.

Closed Loop’s website, which once prominently touted its furnace concept, is no longer active, and calls to its offices have not been returned for months.

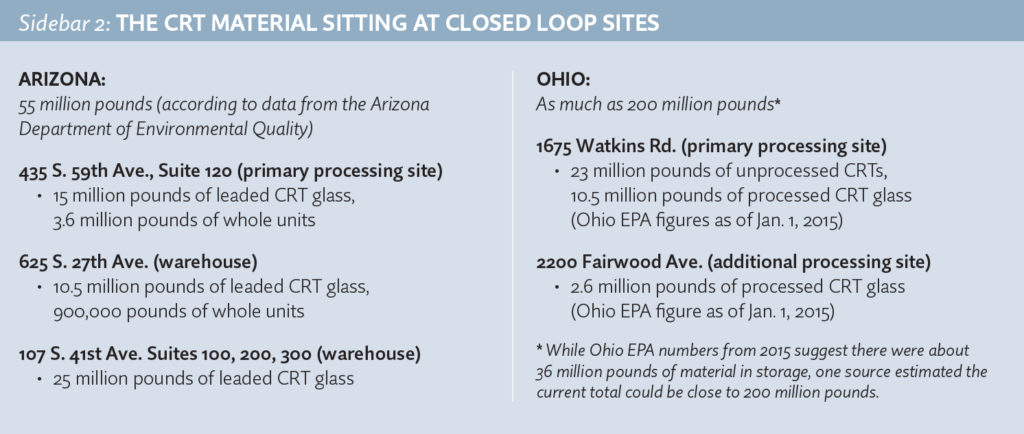

While Benham would not provide updated estimates to E-Scrap News of how much CRT material has been stockpiled by Closed Loop, data from Arizona and Ohio suggest hundreds of millions of pounds of CRT material could be on the ground (see Sidebar 2 below).

In Arizona, an estimated 50.5 million pounds of leaded CRT glass sits in Closed Loop storage sites and another 4.5 million pounds of intact CRTs have yet to be dismantled, according to records compiled by the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ).

Meanwhile, in Ohio, the magnitude of Closed Loop’s stockpiling is less certain. The most recent official numbers come from the beginning of 2015, when Closed Loop self-reported to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency that it was storing 23 million pounds of unprocessed CRTs and about 13.1 million pounds of processed CRT glass at sites in the state.

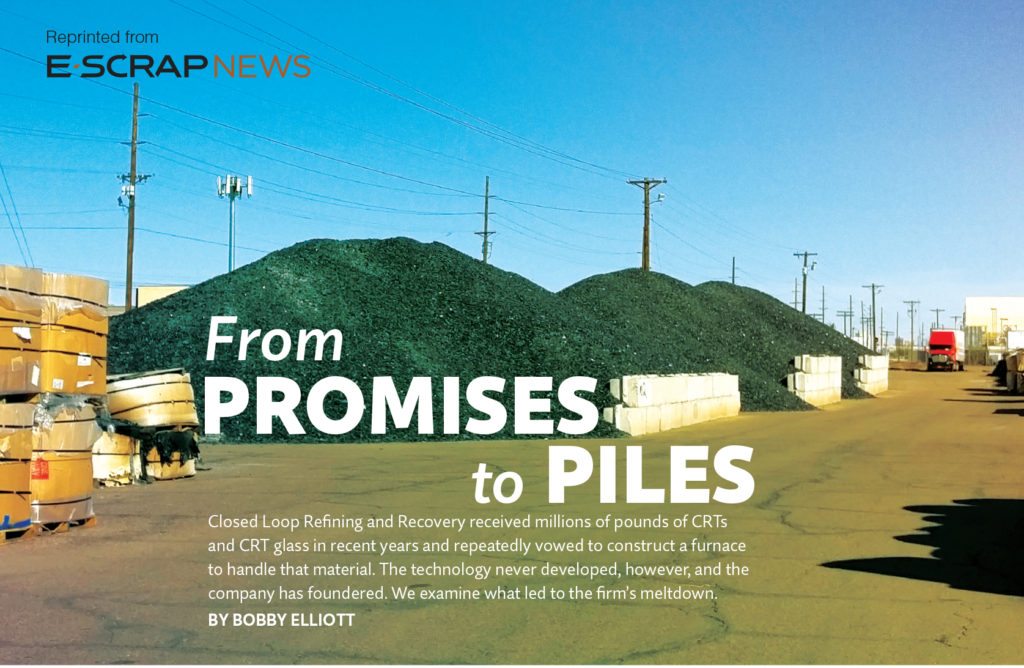

CRT glass sitting outside Closed Loop’s primary processing site in Phoenix.

One industry source with knowledge of the operation, however, estimated that there now could be as much as 200 million pounds of CRT material currently in storage between multiple sites in Columbus.

Ohio EPA spokesperson Heather Laurer said the agency is working with the landlord of the company’s primary processing site in Columbus to get an accurate assessment of the amount of material on-site.

“We just don’t have updated numbers,” Laurer said.

Delays and financial struggles

Since its founding in 2010, Closed Loop repeatedly promised to build multi-million dollar furnaces in Ohio and Arizona to recycle CRT glass and produce two marketable commodity streams – glass and lead.

After establishing its Arizona site, the company said in October 2010 it would complete “phase 2” of its construction by early 2011 and have a furnace built in Arizona.

The company then pivoted its attention to Ohio, where it opened a facility in 2012 that was also slated to have a furnace.

In March of 2014, the company prepared a press release stating it would build a furnace in Ohio and have it operational by 2015. It also reasserted its claim that an Arizona furnace was coming. At the 2014 E-Scrap Conference, David Cauchi told attendees the same thing.

Later, in November 2014, Cauchi told E-Scrap News that “worst-case scenario, we’re looking at October 2015” for a furnace in Ohio to be built and operational.

Today, the company’s Linkedin page continues to state that “the new technology assures the North American e-waste recycling network that CRT glass can be managed economically and safely in North America.”

In interviews, Benham insisted the company put all of its funds into existing operations and research and development for the furnace build-out, despite the fact that no furnace construction has ever commenced.

Some of the company’s contracts were significant. According to government contractor tracking website GovTribe, between August 2011 and January 2015 the federal prison system paid Closed Loop nearly $2.5 million for CRT recycling services.

The company’s Arizona location also benefited from its proximity to California. State records show that California recycling companies began shipping loads of bare CRT tubes to Closed Loop’s Phoenix site in April of 2010. And, until recently, those loads, averaging about 40,000 pounds a piece, kept coming on a monthly, and sometimes daily, basis.

Between April 2010 and April 2016, just under 120 million pounds of tubes were shipped to Closed Loop by California companies operating under the Golden State’s electronics recycling program

Closed Loop also received material from a wide range of manufacturer-funded state programs.

“They were getting material from other state programs and other recyclers who were using them as a downstream vendor,” said Jason Linnell, the executive director of the National Center for Electronics Recycling (NCER). “I don’t think there’s a question that they were significant.”

In virtually all of those arrangements, Closed Loop was getting paid to take on glass. But the company nevertheless insisted it needed outside funding to push forward its furnace plans. And toward the end of 2014 a potentially major funding source came – and then fell through.

According to court documents filed by Closed Loop, the company believed it secured a $16 million loan from New Jersey-based Velma Marketing in December of 2014. The money was to be used “for construction of its proprietary glass furnace and other equipment at its Arizona and Ohio locations,” a legal complaint states.

But Velma never followed up on the intention, and Closed Loop sued the company and its owner in June of 2015 for failing to provide the funding or return a $100,000 refundable deposit put down by Closed Loop.

Closed Loop won the case, court records show, but Benham this spring said the two sides still have not been able to resolve the issue.

The OEM equation

In interviews, Benham was quick to point the finger at OEMs themselves for Closed Loop’s inability to build a furnace. Brand owners are responsible for financing electronics recycling programs in more than 20 states nationwide, and Benham said those companies failed to cover the increased costs for “properly recycling” material coming into the e-scrap stream.

“It’s really dependent on market conditions and the support of OEMs, and I don’t know if OEMs want to support a domestic solution at this point,” Benham said. “There isn’t a company in the marketplace that isn’t severely hurting.”

While Closed Loop did not hold direct contracts with individual OEMs, the company received material from OEM-contracted recyclers needing an outlet for CRTs and CRT glass.

Doug Smith, the director of corporate environment, safety and health for Sony Electronics, confirmed that partners of the company did ship material to Closed Loop. Smith said a test convinced him the furnace technology could work – and work well.

“Whereas other companies had tried to treat the glass and remove the lead, nobody did it as well as they did on their pilot test,” Smith said. “I was impressed with their technology. They had a plan, but the market dynamics continually changed and it just wasn’t compelling enough for investors.”

Smith indicated that it was not Sony’s responsibility to ensure Closed Loop’s finances added up. According to Smith, Sony contracts with recycling companies certified to either the R2 or e-Stewards standards, and he said those firms are responsible for conducting their own due diligence on downstream vendors, including Closed Loop. “If it’s a certified company, they have to perform due diligence on their second- and third-tier vendors,” Smith said.

Walter Alcorn, the vice president of environmental affairs at the Consumer Technology Association, noted downstream due diligence is “not fool-proof and different companies have different risk tolerance levels.”

Tricia Conroy, the executive director at MRM, which that manages state program obligations for a wide range of electronics manufacturers, including Panasonic, Sharp and Toshiba, said her group actively reviews and approves downstream outlets for material managed by MRM’s recycling vendors.

She said MRM held meetings with Closed Loop but never “committed to working with them because they had to have a furnace and they never did.” “We are always interested in the development of domestic glass processing capabilities. Like everybody, we’d like to see more processing capacity,” Conroy said.

Who’s responsible for potential cleanup?

With Closed Loop on the verge of shutting down and huge quantities of glass sitting at company locations, regulators, landlords and others are beginning to sort out the details around moving the material to final disposition – a proposition that will likely carry a significant price tag.

Arizona landlord Jim Harrison of Harrison Properties told E-Scrap News, “The company has no money – they can’t even pay rent – so the last guy standing is me.”

In Columbus, meanwhile, Garrison Southfield Park has sued Closed Loop for nearly $4 million in back and future rent at the company’s primary Ohio processing site and is attempting to also gain millions of dollars to help clean out the location. The lawsuit is ongoing and court documents indicate that Garrison is now in possession of the space.

The status of Closed Loop’s additional site in Columbus and two additional warehouses in Arizona is unclear.

Benham said it would primarily be the responsibility of landlords to clean out the facilities if Closed Loop loses control of them. “At the end of the day, everything’s inside, everything’s OK and it will all get cleaned up,” Benham said. He added that Closed Loop would be “helpful” in assisting with any cleanup necessary.

It may not just be landlords and Closed Loop that are deemed responsible for the cleanup, however.

Jeff Hunts, who manages California’s consumer-funded electronics recycling program, said there is “absolutely” a possibility that California suppliers of Closed Loop could be required by California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) to retrieve and dispose of the material that is in storage.

“In California, an electronic waste recycler that generates a waste CRT and then ships that waste CRT to an intermediate facility is obligated to be able to demonstrate that the material ultimately moves on to a compliant ultimate disposition,” Hunts explained. “In the case of Closed Loop … DTSC emergency rules, in theory, could be used to obligate a California recycler to redirect material.”

A similar scenario has actually played out once before. In 2013, Dow Management left behind more than 9 million pounds of CRT material in Yuma, Arizona. With the owners of Dow nowhere to be found, California authorities required Dow’s suppliers to retrieve and dispose of the material that was in storage.

In 2014, Closed Loop’s Phoenix site received a violation for improper storage.

California’s Hunts noted the Arizona DEQ is working with Closed Loop to arrive at a more agreeable solution. “Given the reported troubles that Closed Loop is facing, we all have questions about how any accumulations or inventories will be managed,” he said.

According to Caroline Oppleman, a spokesperson for the Arizona DEQ, Arizona companies that worked with Closed Loop could also be required to fetch CRT material sent to the facility.

“We potentially could require facilities located in Arizona to remove stored CRT material that they supplied to Closed Loop in Arizona and have them send it further downstream for recycling and final disposition,” Oppleman said.

She added, “We don’t have jurisdiction over facilities that are located in other states that supplied material to Closed Loop in Arizona.”

Laurer, the spokesperson from Ohio EPA, declined to say whether Ohio companies would be asked to retrieve material from Closed Loop’s sites.

Linnell from NCER said he thinks other states with electronics recycling programs could follow California and Arizona’s lead but might “be challenged to find the authority to do it.” “Some are going to investigate it for sure,” Linnell stated.