As recycling companies seek to improve workplace safety amid an industry-wide increase in on-the-job fatalities, experts at a recent industry summit advised managers to focus their attention on — and for top executives, even to attend — the regular pre-shift safety meetings.

That was one takeaway from the Waste Advantage Safety Summit, held in March, which was convened after a troubling rise in solid waste and recycling industry fatalities. The Bureau of Labor Statistics late last year reported an increase in MRF worker deaths in 2023, finding that solid waste collection rose from seventh to fourth on its list of most dangerous jobs.

That’s the highest it’s been in the government’s 20-year span of reporting such numbers, said David Biderman, a consultant and past leader of the Solid Waste Association of North America, SWANA, and he called it “very disconcerting.”

“There’s no single reason for the 70% increase in collection worker fatalities or the record number of MRF worker fatalities in 2023,” he said during the summit. Additionally, he suggested it may be an undercount, as temporary workers are not counted in those BLS figures.

There are societal-wide factors at play. Collection workers are constantly in contact with drivers on the road, and “post-COVID, driving habits changed,” Biderman said. “There are more distracted drivers than ever.” The locations people are driving have also changed, with work from home producing more traffic in suburbs rather than in office-heavy urban areas.

Worker turnover has also increased post-COVID-19, with wages rising in other driving careers like Amazon or FedEx delivery, Biderman noted. With turnover comes challenges in instilling the importance of safety.

Causes aside, the summit brought together stakeholders highlighting various areas of safety concern and how to reduce dangers on the job. Those range from very specific on-the-job behavior change to employer-level culture shifts. For example, “while some employers tell their frontline workers that safety is really important, they also impose productivity requirements that are higher and higher,” Biderman said.

Company culture from the top down is key, he said.

“It means showing up at that safety meeting that starts at 4:30 in the morning before the drivers roll out,” Biderman said, noting he has conducted early-morning safety meetings both with and without company executives present. “When do the drivers and helpers pay more attention? When the owner of the company is in the room. So the owner of companies needs to be at these safety meetings; it sends a signal to the front line that safety matters.”

Updated, relevant safety materials are key

Biderman advised safety managers to make it personal when they talk about safety with workers. Highlight how safe behaviors directly connect with going home to one’s family after a shift, for example, or use specific visual examples of poor safety behavior to capture worker attention during safety meetings.

For the latter, Biderman provided photos of a New York City municipal collection truck that flipped onto a highway near the Lincoln Tunnel on a Friday afternoon, and of a collection worker riding in a truck’s hopper on a Long Island highway.

Nathan Brainard, division president at Insurance Office of America, added it can be helpful to change up the format of information being shared: Use photographs once, an in-person presenter the next time and a video clip the next.

“If you change up the medium in which the data is being presented, you have a much higher likelihood that people are going to be receptive to it and remember it,” he said.

And it’s vital to update safety materials frequently, added Paul Zambrotta, director of safety at New York-based Boro-Wide.

“The best are the ones you make yourself,” he said. “We used to use safety video and training that you bought the CD, you popped it in and, you know, you put people to sleep.”

Using safety materials with relevant, current hazards collection workers face — like cell phones, e-bikes and scooters — is far more engaging, he said, and all it takes is hanging around the truck gas pump in the morning to hear the latest war stories of what drivers are facing.

It’s up to company or agency leadership to make sure those meetings are yielding that type of engagement, added Dave Bennett, public works solid waste director for the city of Scottsdale, Arizona.

“You, as leaders in your industry, should be down there every once in a while monitoring and seeing what they’re presenting,” he said. “You’ve got to keep on top of that, that they’re just not reading something off, that they’re giving visual examples of, ‘Hey, Bob just had an incident last week, here’s how we can learn from it.'”

Tackling fire danger has multiple prongs

No recycling industry safety discussion would be complete without mention of the ever-increasing occurrence of fires in facilities and trucks alike.

While the hazards — primarily lithium-ion batteries but other improperly recycled flammable items as well — are different from those posed by distracted drivers or workers cutting corners, a similarity is that safety training is also part of a proactive approach to fire dangers. It’s especially important to remember that when training new hires, said Chris Ball, vice president of environmental health and safety at WM.

“Drivers in particular really need to know their equipment, what fire suppression is available to them, their routes, what are the right protocols to handle, is there a safe location for that driver to dump a load if that’s ultimately what’s needed to deal with that,” Ball said. “Really look at that training aspect out there as you move forward.”

Once a fire is started, it’s important to have a plan in place for how a facility will fight it, to determine who is on the front line for fire control, said Ryan Fogelman, a partner at fire suppression system supplier Fire Rover.

“The reality is that your front line can be your fire department at 2 in the morning, or your front line can be a Fire Rover system that actually fires and shoots and does everything that we need to do, and really the fire department is backup to that,” he said.

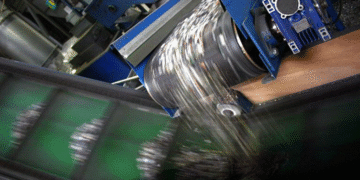

In the space between worker training and full-blown fire suppression, emerging equipment is making advances at identifying batteries as they enter recycling facilities, before they have a chance to go into thermal runaway, the industry term for heating up and potentially sparking a fire.

One example is Visia, an equipment supplier that provides X-ray and camera systems targeted for MRFs and e-scrap facilities and designed to be placed at presort conveyors, inbound lines, tip floors, anywhere material comes into the facility, said Raghav Mecheri, company CEO. The vision systems look for battery-containing devices and other flammables or general hazards, using a laser to indicate the object’s position on the moving sort line and allow a manual sorter to pull the object off.

“The goal is to identify it and alert people on-site to actually get that out of the material stream,” he said.

As one example, Mecheri said MRF operator Rumpke uses Visia on presort lines at a MRF, where it detects and assists with removing 20-40 batteries a day. Altogether, the system is installed in about 25 sites, including MRFs and e-scrap companies.