This article appeared in the March 2025 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The potential merger of U.S. Steel, one of the country’s largest users of recycled metal, with other major steel companies could change the industry’s global landscape. But when it comes to immediate impact on local scrappers and municipal collection programs, mergers and acquisitions generally take a back seat to cold fronts and seasonal thaws, several stakeholders said in recent interviews.

“We’ve had a winter that’s been rougher than we’ve had in the past few years,” said Brad Cook, general manager of the Premier Metals scrapping company in Rochester, New York. “That’s slowed the retail trade down in 2025. Come spring, we’re preparing ourselves to clean the corners and get things going.”

Beyond nature, the extent of any future industry change could depend on how well a given company goes green — and not the green usually associated with recycling.

“Does one company’s relative position put the combined company into a stronger position? Companies in this spot would look at long-term sustainability with a sound economic premise,” said Michael E. Hoffman, CEO of the National Waste & Recycling Association. “A combination of companies could make (incorporating recycled steel) go a little faster.”

What hasn’t been fast is U.S. Steel’s acquisition process, which was subject to federal approval of foreign investments and has therefore moved at a glacial pace, allowing other players to join the game.

Where the deal stands

The proposed $15 billion acquisition of U.S. Steel by Japanese company Nippon Steel has faced a lot of scrutiny since it was announced in December 2023. The deal has rare bipartisan opposition; then-President Joe Biden blocked the deal in January, citing national security risks of a foreign owner, while successor President Donald Trump has also continued to oppose the deal after taking office.

After meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, Trump said in early February that Nippon Steel will shift to investment rather than a takeover. But that plan could fall to the wayside if Cleveland-

Cliffs can buy U.S. Steel, which Cleveland-Cliffs CEO Lourenco Gonclaves told CNBC in January he wants to do in partnership with Nucor Corp.

The companies represent four of the top 25 steel producers in the world, according to numbers from the World Steel Association: Nippon Steel is fourth, Nucor 15th, Cleveland-Cliffs 22nd and U.S. Steel 24th.

Requests for comment from all four companies went unanswered, but industry experts say recycling is a key component of domestic production.

“Steel producers in the United States recycle significant amounts of steel scrap in their production processes,” said Kevin Dempsey, president and CEO of the American Iron and Steel Institute. “Large steel companies clearly have a significant impact on the consumption of steel scrap, and logically then they also have an impact on recycling efforts.”

Doing their part

The companies made an impact on the recycling industry long before any merger talks surfaced. Nippon Steel was one of 15 founding members of the Japan Used Can Treatment Association in 1973. The group was renamed the Japan Steel Can Recycling Association in 2001, advocates for greater steel recycling and hosts and holds educational events in schools.

U.S. Steel has, in the words of CEO David Burritt, woven sustainability into its way of conducting business. In 2021, U.S. Steel acquired Big River Steel in part to bolster its sustainability initiatives. The Osceola, Arkansas, facility earned the ResponsibleSteel Certified Steel designation in fall 2024 thanks in part to a recycled metals use rate of around 90%. Overall, the company in 2023 recycled more than 5.2 million tons of purchased and produced steel scrap while producing 22.4 million tons of raw steel, according to the U.S. Steel 2023 sustainability report.

Cleveland-Cliffs, meanwhile, recycled 6.6 million tons of steel scrap and recovered iron materials, according to its 2023 sustainability report. Nucor eclipses both, recycling 20 million tons of steel annually.

Each company has made individual recycling- and sustainability-related commitments. Those initiatives would presumably continue under combined corporate umbrellas, but what impact that has on steel prices or other aspects of the recycling system remains unclear.

An analysis of recent mergers fails to yield substantive answers, thanks in large part to their timing. Cleveland-Cliffs acquired AK Steel in 2020, right around the time the COVID-19 pandemic began; the pandemic caused iron and steel scrap prices to fall 17.4%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, to $354 per ton.

The Tata Steel/Thyssenkrupp Steel merger in Europe and ArcelorMittal/Essar Steel deal in India happened in 2021, when mid-pandemic supply shortages caused scrap prices to soar from $536.10 per ton in December 2020 to $739.12 months later.

Overall, scrap supply has remained relatively consistent historically, according to Brian Raff, vice president for sustainability and government relations at the American Institute of Steel Construction. The only potential impact could come if something drastic like the shutdown of a company or major mill were to happen.

“A fabricator really doesn’t care” what’s happening at the major companies, he said. “They’re buying steel to meet project requirements. If there’s more capacity (resulting from a merger), if there’s more steel, that’s great.”

Recycling rates likewise show no major movement based on mergers. Data from the American Iron and Steel Institute shows the North American steel recycling rate to be about 69%; it has remained above 60% since 1970.

That consistency comes with the industry’s maturity. The recycling infrastructure in the United States is more sophisticated than that of steel-producing nations like India and China, Dempsey said. Many of the nation’s nearly 18,000 scrap and recycling facilities have been in business for decades, and the National Materials Council estimates there are more than 24,000 municipal recycling programs operating in the U.S.

How steel recycling works

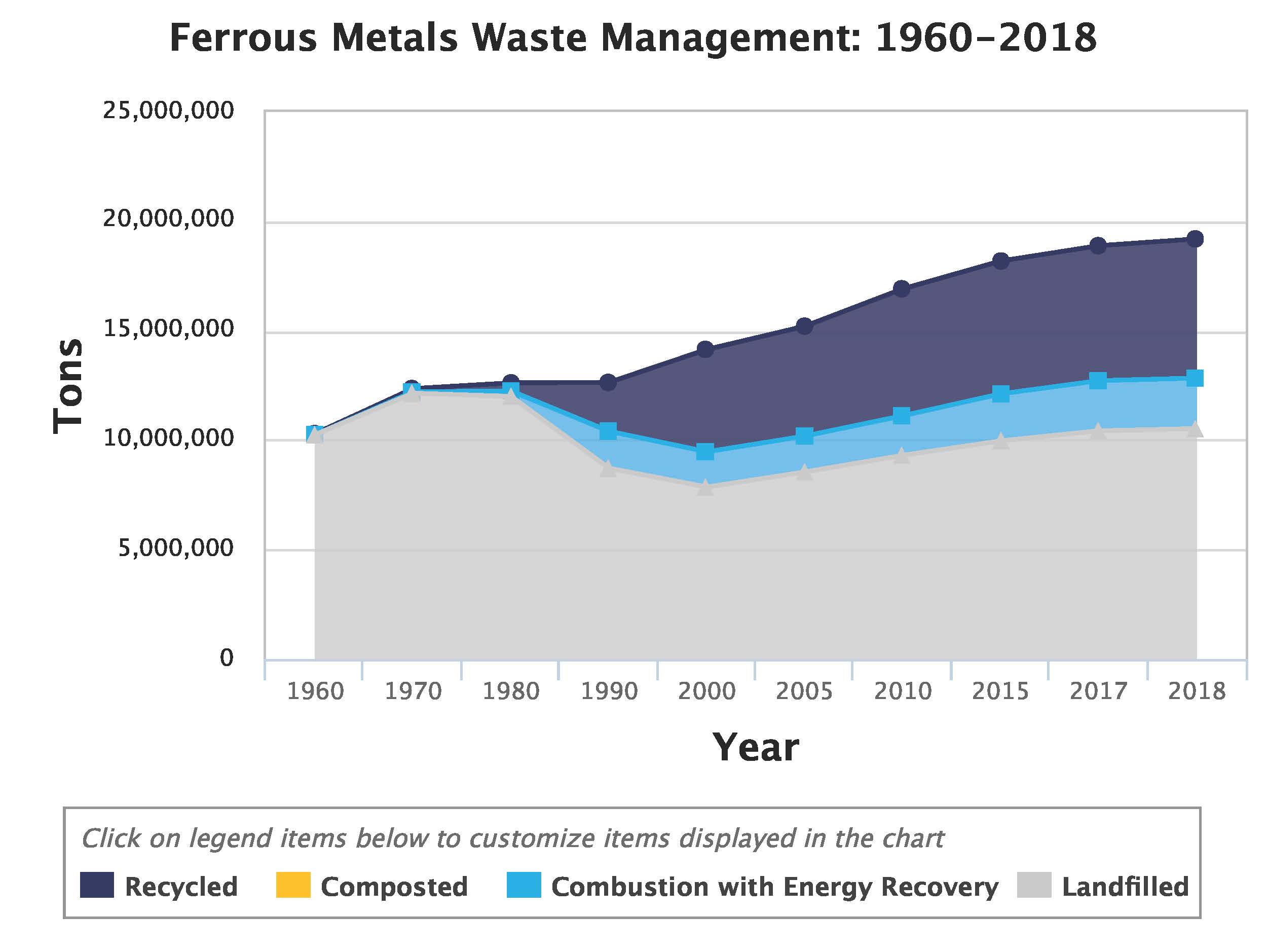

Municipal recycling programs collected 6.36 million tons of steel and other ferrous metals in 2018, according to the U.S. EPA. Cans collected at the curb, for example, are sent to scrap processors, who crush and bundle them before selling to steel-producing companies, Dempsey said.

But curbside activity makes up less than 1% of the steel scrap used by U.S. steel producers, Dempsey said.

Most of the recycled material steel producers use comes from two places.

Recycling processors buy old cars, construction leftovers, broken appliances and other scrap steel, then cut or bale the metal to sell to steel mills.

Prompt scrap — metal that never reached the marketplace, such as leftovers from automobile component manufacturing — is collected by steel companies for reuse.

Mills melt the scrap down at nearly 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Impurities rise to the surface and are skimmed off. The molten metal is shaped and solidified before it’s transported to factories. A recycled item can take its new form in as little as two months.

The cycle never has to end due to steel’s inherent reusability without degradation; the production process allows impurities to be removed. Even those impurities, collectively known as steel slag, are recycled into asphalt and other materials. The Can Corporation of America estimates about 75% of all steel ever produced is still in use in some fashion.

“Most steel scrap can be recycled into virtually any new steel product, so a steel can or deconstructed steel beam can become a new steel beam, or a car door, refrigerator or steel container,” Dempsey said.

Finding scrap steel came more into focus as mills shifted to electric arc furnace technology in the 1970s and 1980s — around the time steel recycling rates began a decades-long climb from around 150,000 tons in 1970 to more than 2 million in 1990, according to U.S. EPA data. These furnaces use electricity to heat material and are fed recycled steel. Traditional blast furnaces need iron ore and coal-based fuel to operate.

Eliminating the need for mined materials, combined with the decreased emissions resulting from production, makes EAF production more sustainable, Hoffman said. Nearly 71% of U.S. steel production happens via EAF.

“The decision to go to electric arc furnace was economic,” he said. “If we were going to produce steel domestically, we had to move to a production method that was more economical.”

All new steel could be made from recycled steel, but scrap scarcity prevents that on a global level, according to the World Steel Association. The average lifespan for a steel product is 40 years, which the organization said prevents a continuous flow of enough product to meet demand.

Dempsey noted the U.S. produces enough ferrous scrap to export about nearly 18 million tons of scrap per year. Hoffman said the country’s long-standing automotive industry has created a generational scrap flow that helps give domestic recycling a leg up on the rest of the world.

Where is the industry going?

There may not be enough scrap to meet producers’ demand, but Cook said the supply domestically always seems to be there — “I’ve been in the business for more than 25 years, and I’ve never seen it stop.”

So any movement by U.S. Steel or other parties may not mean much in the grand recycling scheme. Rather, Dempsey said, companies that can sort scrap more accurately by contaminant level have the advantage, because “the recycling of incoming scrap steel can best be matched to the new steel product’s end use.”

Imports could also have an impact. Whoever owns the major domestic steel companies, they could see an uptick for demand if proposed tariffs on foreign products take effect. That could drive up scrap prices, but since U.S. mills run at about 75% capacity, there’s room to meet a potential demand surge, Raff said.

Dollars are the most important factor, Hoffman said: The bottom line will trump any short-term political motivations when it comes to recycling.

“I would make the case, if you look out 10 years, more metals will be made with recycling, with a green emphasis,” he said. “If you want true, long-term environmentally sound outcomes, they have to stand on the back of a sound economic model.”