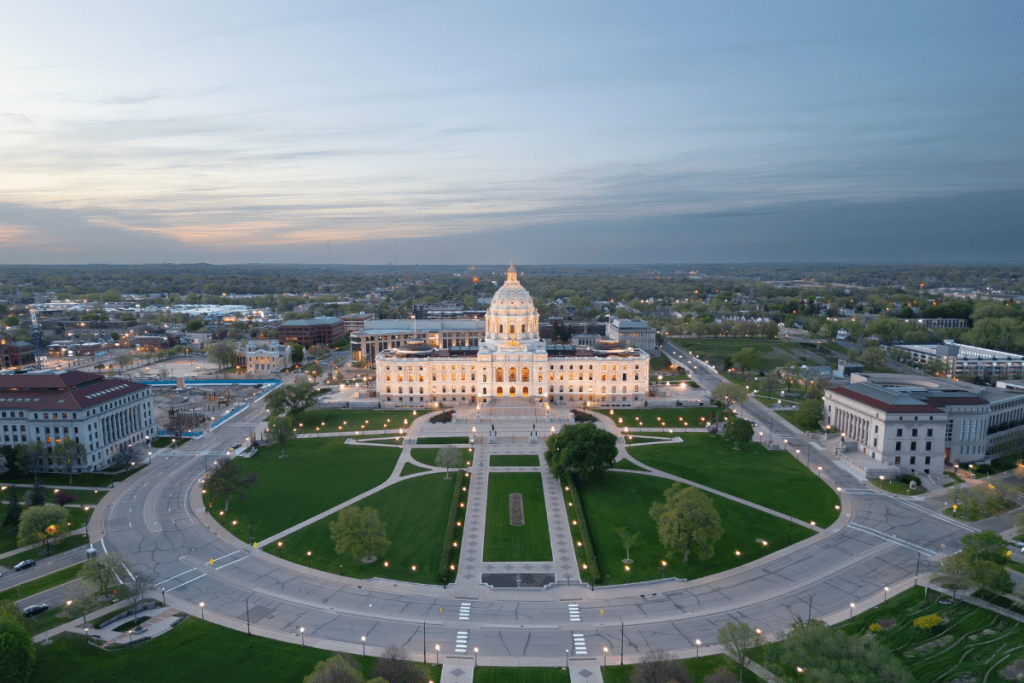

Minnesota lawmakers approved an EPR bill during the 2024 legislative session, and the governor signed it into law in May. | Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

Stakeholders behind Minnesota’s successful extended producer responsibility push said it was clear that radical change was needed in the state’s recycling system, during a recent webinar.

“For us, we saw that we needed improvements and change. That was a big motivator,” Mallory Anderson, representing the Partnership on Waste and Energy, said during the Aug. 7 webinar hosted by the Product Stewardship Institute.

“EPR was the clear solution,” she added. “We’re excited for an infusion of attention and education around recycling.”

Lucy Mullany, director of policy at Minnesota-based nonprofit MRF operator Eureka Recycling, said EPR is just part of the “radical change” the state needs.

“We are going to need other policies, but I am looking forward to the work ahead,” she said.

The process of building EPR legislation started in 2021 with support from PSI and took lots of collaboration and feedback from stakeholders, Anderson said. Minnesota became the fifth U.S. state to pass EPR for packaging after adding the program language into the 2024 Environment and Natural Resources Budget bill, which the governor signed on May 21.

Kirk Koudelka, assistant commissioner of land policy at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, said some of that collaboration was interstate: Minnesota borrowed Washington’s definition of a producer, and it was the “first time we’ve ever had a definition be a page long.”

However, the state also made some distinct choices. The producer responsibility organization must be chosen by Jan. 1, 2025. The stewardship plan implementation date is February 2029, followed by cost reimbursement starting in April 2029. Koudelka said that’s a longer timeline than many other states, but it was an intentional move.

“It may take a little bit more time. but we believe it will have a better end result,” he said.

Anderson said one challenging area was chemical recycling, which is a “complex and difficult issue.”

Exemptions were also a challenge, with “people coming out of the woodwork to claim their product was unique and needed exemptions,” she said. In the end, there were very few exemptions codified in law, and instead the lawmakers set up a process for future applications for exemptions.

The exemptions that were made in law were to ensure passage, Anderson added, such as an exemption for paper mills due to pushback from the paper industry.

Several groups wanted things included in the law that did not make it in, Anderson said, like target rates, and the Can Manufacter’s Institute wanted to package a deposit return system for beverage containers with the EPR law.

“We really struggled with that issue here,” she said. “We understand the value and benefits of those programs but just thought that keeping EPR and DRS separate was important,” largely because “we did not think we would get the same level of support” if they were packaged together.

Mullany said Eureka at one point stopped supporting the Senate version of the bill, in part due to changes in how reimbursements were distributed, but those concerns were resolved. She said that while haulers are often cast as a roadblock to EPR legislation, they have legitimate concerns, especially around competition and conflicts of interest.

“It’s important to have haulers at the table,” she said. “I think that they did offer some improvements to the bill that were helpful. I think in a lot of states they are being cut out of the process, which is not the best approach to take.”

Mullany noted that while she thinks many pieces of Minnesota’s law are stronger than in other states, there are still question marks about rates and dates. Koudelka cautioned not to let “perfect get in the way of good enough.”

“We needed to make a change,” he said. “If something wasn’t solved in this bill, the process is built out to continue to have those conversations. This isn’t done.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated on Jan. 8, 2025 to correct a quote.