This article appeared in the June 2024 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Local recycling programs have always experienced some level of fluctuation in how much and what variety of material they accept, but operators said a recent trend of program contractions and closures will need policy

intervention to correct.

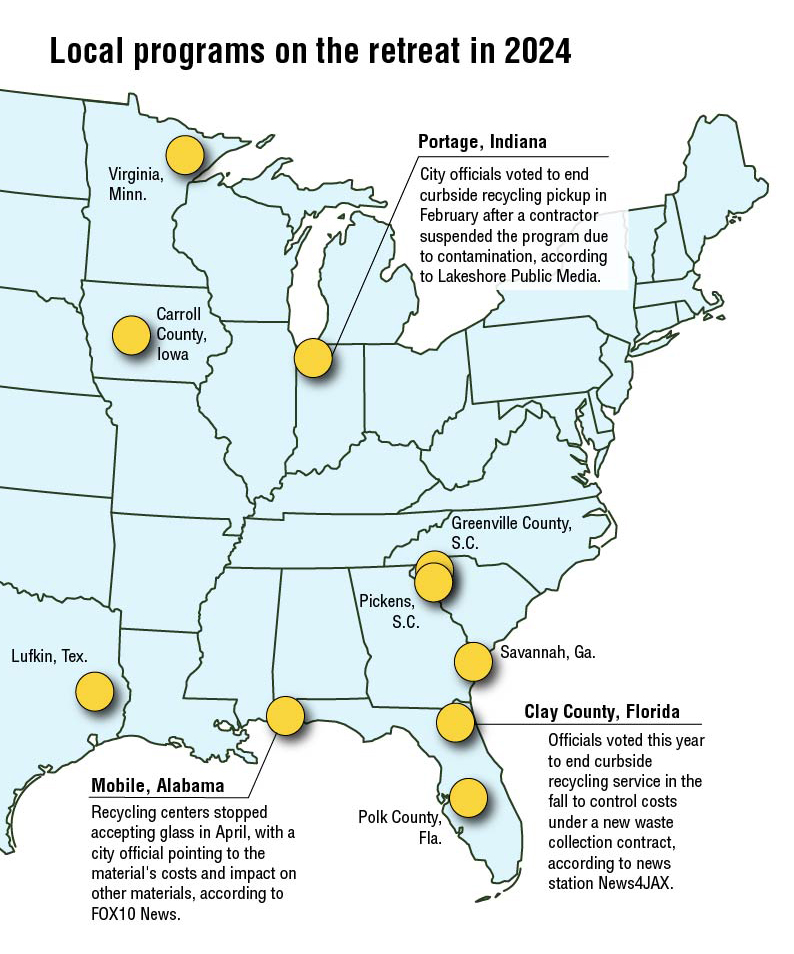

Every month in the print edition of Resource Recycling, the Programs in Action section is filled with program reductions or closures, most citing costs and contamination. April’s updates stretched from Greenville County, South Carolina, to Clay County, Florida; Idaho Falls, Idaho; and Portage, Indiana.

A press release from the Greater Greenville Sanitation District said that “it is imperative as a community service funded by tax dollars that Greater Greenville Sanitation manage the funding wisely and be good stewards of the monies received.”

As the cost of recycling is more than four times the cost of landfilling, Greater Greenville Sanitation made “the difficult decision to end recycling collection.”

April had bright spots, too: Chesapeake, Virginia is thinking about bringing its program back, and Columbia, Missouri, and Walla Walla, Washington, brought back programs curtailed in the past.

So are local programs dropping off, or is this just a natural ebb and flow? Operators on the ground said there’s definitely been a contraction of programs, and while there have been a few hopeful signs lately, it’s by no means a strong reversal trend.

Heather Trim, executive director of Zero Waste Washington, said the state is “a little bit in a holding pattern” because of all the work being done to pass an extended producer responsibility law for paper and packaging, and organizations there are in “‘wait-and-see mode.”

“I think what happened a lot of stuff went out and stayed out after National Sword,” she said, referring to China’s decision in 2018 to stop accepting most imports of materials meant for recycling, particularly plastics. “Things might come back, but at this point, I haven’t seen anything be added back.”

Experiences on the ground

Experiences on the ground

Trim said in two of Washington’s bigger cities, Tacoma and Olympia, glass was removed from curbside collection several years ago, and Olympia also stopped accepting cartons.

In King County, where Seattle is located, plastic bags and film were removed from the curbside program, along with shredded paper and aluminum foil. Some smaller towns, including Walla Walla, also stopped accepting plastic, Trim added.

However, organics collection programs are growing, she said, including curbside.

Dan Weston, a materials management and recycling policy coordinator at the Washington Department of Ecology, has been checking in on what about 300 programs across the state collect for several years, starting in 2020.

His department uses a list of 70 or so different materials to track what programs are collecting, how they are collecting it and how frequently. In addition, Weston said the department asks which MRF the programs use, which hauler, what bin colors they use and if they had made any changes to the program as a result of National Sword.

Of the 334 communities listed, 184 responded that they made changes as a direct result of China’s policy change, defined as between late 2017 and the end of 2020 in the survey. Another 74 said they didn’t, and the rest didn’t answer the question.

Of the 55% that made changes, 24 communities removed glass entirely, and a few others moved to glass drop-off only. Another 29 reported they chose to no longer accept plastics 3-7, and two stopped accepting all plastics. Five communities said they both stopped accepting glass and plastics 3-7.

Smaller reductions in what resin types or forms of plastics were reported by 45 communities, and 26 communities stopped accepting plastic bags or film. Three stopped accepting mixed paper, and nine reported charging higher fees or rates.

There were far fewer changes in 2021. Of the same 334 communities, 46 reported changes in 2021.

Bryan Ukena, CEO of Recycle Ann Arbor, a nonprofit MRF operating in Michigan, said the dynamics are a little different in the state because many MRFs are publicly owned. There is currently more capacity being built out around the state, he said, but there was definitely a loss of collection range in programs over the past few years.

“We had programs, like individual curbside recycling programs, that either picked up materials as recycling and then threw it away or just quit recycling because of the market downturn,” he said, and even when the markets returned, most programs didn’t.

“Once they stop, it’s really difficult for them to start back up again,” Ukena said, adding that a couple of large suburban communities around Detroit started programs back up. “I wouldn’t call it a trend, but I see it happening.”

Miriam Holsinger, co-president of Minnesota-based Eureka Recycling, said while recycling mandates in the state paired with state Select Committee for Recycling and the Environment funding has helped keep many smaller programs running, that hasn’t been foolproof.

The city of Virginia, Minnesota, discontinued curbside recycling on Feb. 6 of this year, opting for drop-off only due to rising costs of recycling, Holsinger said, but “in Minnesota they’re the only ones I know that have reduced services.”

Contamination, rising costs and volatile markets are the most commonly cited factors in reductions and closures.

Holsinger said the rising cost of insurance isn’t helping matters, especially paired with inflation.

“Recycling is such an interesting industry because it’s this combination of public and private and people making these individual decisions to recycle this product, combined with systems,” she said.

Solutions in the field

Weston said in an interview that extended producer responsibility is one very strong way that policy can be used to bolster recycling programs. If not EPR, then mandates for brands to use a certain amount of recycled content is another good option, he added.

Washington has such a mandate, passed in 2021, but as it’s been rolling out slowly, Weston said it’s hard to tell what kind of impact it’s had.

Local programs are less interested in projects that turn plastics into long-term durables, he said, such as a park bench, and more interested in a system that will allow plastics to be used six or seven times.

“Our material isn’t being recycled back into bottles … and that is what they would want to see,” he said.

More transparency would also help, Weston added, and a “variety of changes made to the system to beef it up more and make it more defensible before we start repeating the same process we had eight years ago.”

Ukena said Michigan has very low landfill tip fees and raising them would help local programs. The state passed a suite of bills that overhaul the recycling system and that will provide more recycling opportunities for rural areas through mandated county-level recycling targets.

Both Recycle Ann Arbor and Eureka are part of the Alliance for Mission Based Recyclers, which brings together nonprofit recyclers.

Ukena said interest in that model of business is also growing, which could help.

“The message is starting to resonate with some people, and that has allowed us to open things up,” he said. “Instead of being the alliance of, we’re the alliance for,” meaning they’ve started to work with other groups.

Trim noted that on a policy front, composting and recycling policies are starting to be combined, and it’s sometimes hard to tell how much proposed bills should overlap.

For example, in HB 2301, which was signed into law this year, Trim was there was a section that would make bin colors uniform across the state. That section was removed from the final bill this year, she said, but will come back next year: “The question is will it be in a composting bill or EPR bill? Which does it fit better in?”

Holsinger said that dedicated funding, such as the SCORE funding in Minnesota, provides a strong incentive and the kind of steady income that is often a challenge in the industry.

“A lot of people look at it as, oh there are tides of current economic stuff, but they’re not looking at the larger policy position,” she said.

For example, in the early 2000s there was a movement to classify glass that was used as alternative daily landfill cover as recycled, and “we really fought” against that, Holsinger said.

To help combat contamination, Minnesota has made it so recycling isn’t taxed while waste disposal is. Any MRF that has more than 15% residuals would start being taxed as a waste facility, Holsinger said, “so that’s another thing that really makes it so we want to keep our residuals down.”

“It’s nice that there is a state law we can just point to if haulers bring too contaminated loads,” she said. All in all, “the policy is really key.”