This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Ohio’s southeastern Appalachia region is breathtaking. The region is carpeted with picturesque rolling hills as well as steeper terrain and pockets of dense forests.

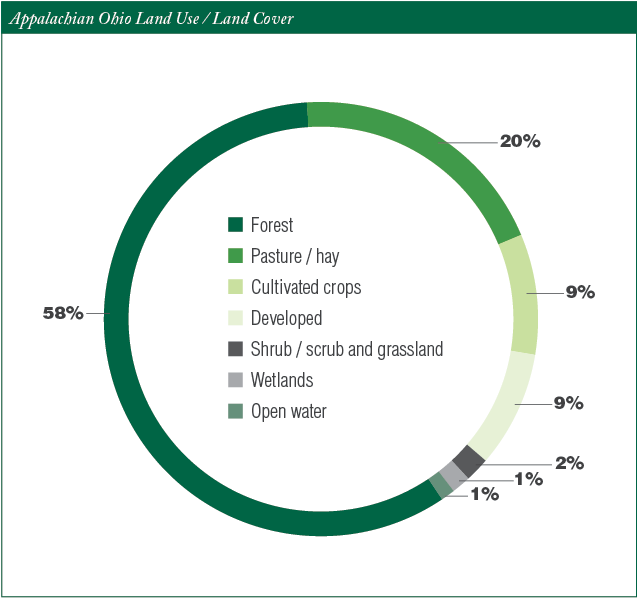

The landscape also finds villages and cities dotting the Ohio River. Less than 10% of the land use in the region is developed; the remaining 90% is forest, pasture, crops, shrub, wetlands and water. The area is also home to Wayne National Forest, 20 state parks and a number of state forests.

Not surprisingly, in this region, integrated waste management is not a one-size-fits-all solution. In fact, many districts have creatively developed their own systems and programs for diversion. These efforts can teach the wider industry some helpful lessons about pushing recycling forward in rural areas.

Economic complications

A good place to start exploring recycling in Appalachian Ohio are the counties of Jefferson and Belmont.

The counties share a regional solid waste authority, which recently became known as the JB Green Team. The authority utilizes a mix of waste management approaches to provide diversion options to a spread-out population – no single community in the jurisdiction has more than 20,000 people.

Similar to most of Appalachian Ohio, at one time the coal mining, iron and steel industries were major employers in the area (the eastern border of both counties is the Ohio River, which forms Ohio’s boundary with West Virginia). The decline in those trade jobs has left higher poverty levels and residents weighing financial options and obligations.

In Jefferson and Belmont Counties, the private sector has a history of providing trash collection but not curbside recycling. Communities and residents looking for curbside recycling options have encountered a situation where the cost of recycling collection is higher than trash collection. In addition, the closest single-stream materials recovery facility (MRF) is 40 miles from one county and 70 miles from the other.

Low population density, winding roads and long distances to the MRF are contributing factors to challenging recycling economics in the area. In order to have drop-off recycling opportunities, and due to the lack of private sector service, the authority needed to establish in-house operations.

Finding a solution

Finding a solution

In the early 2000s, the authority was without a coordinator or director dedicated to overseeing and administering planning and direction.

After taking the steps to fill that position in 2005, the authority next turned to updating its solid waste management plan. The core of this effort was identifying challenges, gaps and assets for each of the six key areas of best management practice in recycling program development: collection, processing, end markets, policy, education and financing partnerships.

One of the results was a plan to restructure and rebrand, and the authority rebranded to become the JB Green Team in 2008. Previously, the two counties utilized separate program names, and the change provided a unified and consistent message to residents. The shift was accompanied by a new logo, squirrel mascots, and opportunities to connect with residents through education and outreach efforts.

At the same time, a feasibility study identified options to streamline operations, maximize available resources, and wisely invest and expand. A system restructure commenced that included streamlining drop-off operations with a transition from barns and trailers to 6-cubic-yard front-load containers throughout both counties. The JB Green Team brand was reinforced with a unified message on containers, including visual labels identifying the proper materials to recycle.

Transitioning to front-load containers also required a capital investment for front-loader trucks and the development of consolidation areas, which helped to streamline transport. Instead of longer hauls, the front-load trucks began tipping recyclables in a designated area in each county, allowing materials to be consolidated before hauling to the processor.

On the end market side of things, the authority made sure to capitalize on an existing partnership with a paper processor in Jefferson County that provides profit shares. The authority has for over 20 years collected materials in a dual-stream program to ensure clean fiber. When the authority transitioned to front-load drop-off containers, service was expanded to add fiber-only collection sites to better service the community and deliver quality product to the end user.

Seeking to model a similar relationship with a glass end market, the authority conducted market research and identified a glass user willing to develop a public-private partnership. With additional capital investments of glass-only toters, the authority implemented a glass-only recycling program targeted at high-volume generators, such as restaurants and pubs. This step helped to remove a large quantity of glass from the commingled stream.

Collected glass in the counties is now recycled into new materials and commingled processing costs have been minimized because less glass is in that stream. Since inception, this program has grown in volume and participation. Today it is operating at full capacity.

The glass transition underscores the value of a city or county having control over collection. When the commingled processor communicated processing costs would become higher due to glass and lack of end markets, the authority could explore other options.

Financing

Financing

A major part of the plan to revamp the counties’ program was a restructuring of revenue streams. To be able to prepare for short and long-term investments, the plan called for diversifying revenue streams.

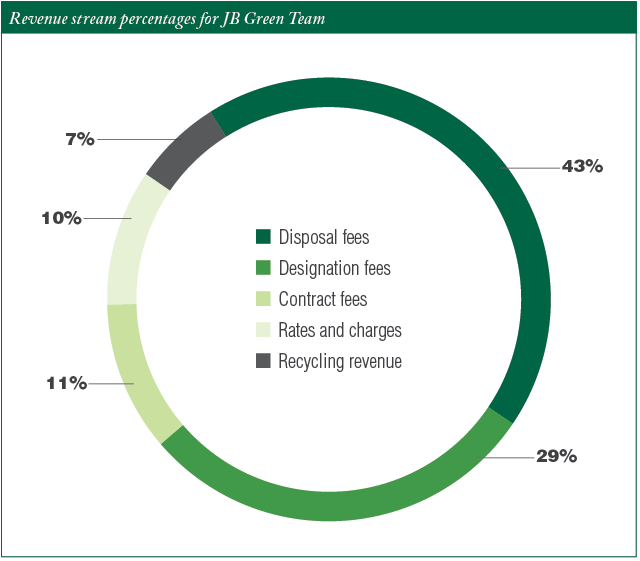

Prior to the restructure, the authority received 68% of revenues from disposal fees, 30% from contract fees, and 2% from recycling revenue. This revenue structure provided funding needed to operate system programs but was unbalanced in that it heavily depended on waste disposal generated from outside the authority to generate the revenue. When this outside waste coming into the privately owned landfill fell by over 25%, it resulted in a significant drop in yearly revenue.

To balance the yearly fluctuations of a waste management system funded by waste disposal revenue, the authority added other revenue streams. Now the system is supported by five different revenue streams: rates and charges, recycling revenue, contract fees, designation fees, and fees on the disposal of waste in the in-county landfill (see breakdown in chart to left). Restructuring allowed the authority to keep and expand recycling despite income and geography challenges. The key was developing a system where financial program costs are more equally shared and distributed.

Of course, rising processing costs for recycling create a constant challenge for program leaders everywhere. Authority officials constantly watch and research options to keep costs at a reasonable and economically viable level.

Action in other jurisdictions

Action in other jurisdictions

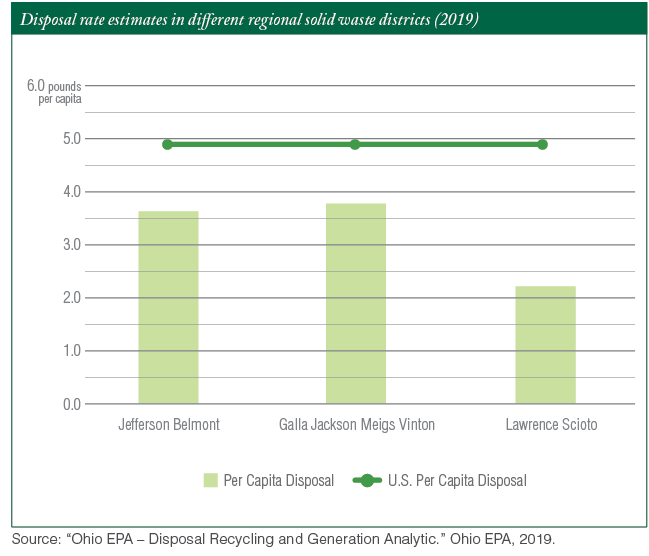

Elsewhere in Appalachian Ohio is a regional solid waste district called Gallia Jackson Meigs Vinton (the four words in the district name are the four counties in the jurisdiction). In this region, no single community has a population over 7,000. Low landfill tip fees have brought an economic challenge to growing recycling.

At one point, the district was a direct service provider, offering collection of recyclables to over 25 drop-off programs. District staffers hauled all materials to the district’s Recycling Center where they were processed and marketed. The district also processed materials from four residential curbside recycling programs, with those four communities hauling their material to the Recycling Center.

This system worked very well until contract changes impacted revenue streams. Program revenues were predominantly received from disposal fees, plus a contract fee. Similar to the system in place under JB Green Team, the revenue structure was dependent on waste generated outside the district and disposed of in the privately owned landfill located in the district. At the same time this waste disposal began to decline, challenging economic times halted the contract fee, leaving the district realizing the financial burdens of system operations. With decreased revenues, as well as aging equipment at the Recycling Center, it was time for the district to reevaluate its system.

Regional leaders considered different operation scenarios, and after several stakeholder meetings, the district chose to embark on a different path, functioning as a program administrator. In this framework, a private-sector service provider would begin collecting and processing material from the network of drop-off locations. The Recycling Center was dismantled and recyclables were hauled to a private-sector recyclable transfer facility (located in a neighboring county) where material is consolidated before sent to the materials recovery processing facility.

Meanwhile, Lawrence Scioto, another Appalachian Ohio regional district, has a network of drop-off recycling sites managed by a private-sector operator. Due in part to a low per capita disposal rate, the district is seeing decreases in annual diversion.

The district is in the process of updating its solid waste management plan, and officials are taking time to look at the system as a whole. Their first steps are defining program assets and exploring long-term planning that will better suit diversion realities for these rural Appalachia counties.

Rural possibilities

The Appalachia region provides unique obstacles for recycling, including complex topography, distance to processors and end markets, less-dense populations, and lower- income communities. But obstacles can be overcome with efforts to seek out solutions through research, assessment, partnering and communications.

Jamie Zawila is senior consultant at RRS and can be contacted at [email protected].

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Finding a solution

Finding a solution Financing

Financing Action in other jurisdictions

Action in other jurisdictions