This article appeared in the May 2021 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Collegiate recycling and waste reduction efforts have advanced greatly in recent decades. From a relatively narrow focus in the 1990s on recovering the basic commodity materials, programs have expanded in both scope and sophistication. Leading institutions are increasingly working toward upstream circular economy solutions, and even average campus programs now target food scraps and other harder-to-recover items.

However, like many sectors of society, higher education has been hit hard by COVID-19. A recent survey of campus recycling and sustainability managers reveals both the near-term setbacks caused by the pandemic and the potential long-term opportunities that could advance waste reduction goals.

Small cities with unique characteristics

Colleges have certain aspects that set their waste reduction programs apart from those of municipalities.

While programs aimed at residential and other sectors largely depend on voluntary action, college campuses operate with a centralized authority that can be leveraged to directly control waste generation and disposal practices through policies like recycled-content purchasing or bans on single-use plastics. Similar to the corporate sector, many schools have sustainability professionals dedicated to implementing climate action or waste reduction plans that guide operational policy.

And of course, colleges have students. Students are both a challenge, requiring a Sisyphean effort to educate each incoming class, and the recycling manager’s ace-up-the-sleeve. As every manager knows, student populations are a source of enthusiasm, high-energy interns and allies who can advocate change outside of the institutional chain of command.

A 2017/18 survey of over 300 sustainability managers conducted by the College and University Recycling Coalition (CURC) offered a pre-pandemic snapshot of campus programs. Asked how they felt about the progress of their school’s waste reduction efforts, 27% of respondents cited “strong momentum” while 24% indicated a more downcast “one step back for every two forward.” Of the 92 schools reporting a diversion rate, a fifth were at 60% or higher, while nearly half (47%) were at 40% or less.

The survey also revealed a disparity. While a growing number of colleges and universities are aggressively pursuing zero waste goals, there’s an equal or greater number that struggle to maintain basic recycling programs in the face of limited resources, change-resistant campus cultures and weak support from campus leadership. Ironically, for some there is a perception the growth of sustainability programs, with a focus on energy, transportation and other issues, has weakened some campus recycling programs by diverting attention and resources.

The survey also revealed a disparity. While a growing number of colleges and universities are aggressively pursuing zero waste goals, there’s an equal or greater number that struggle to maintain basic recycling programs in the face of limited resources, change-resistant campus cultures and weak support from campus leadership. Ironically, for some there is a perception the growth of sustainability programs, with a focus on energy, transportation and other issues, has weakened some campus recycling programs by diverting attention and resources.

A chaotic scramble amid pandemic

Last fall, CURC partnered with Busch Systems, the US Composting Council, the National Recycling Coalition’s (NRC) Campus Council, and the Zero Waste Campus Council on a new survey to gauge how COVID-19 was impacting campus waste reduction programs. The responses from a diverse range of 146 two- and four-year institutions in the U.S. and Canada provide a window to current conditions.

Not surprisingly, they show that the shift to predominantly online instruction has reduced overall waste generation. At the same time, COVID-19 has prompted a spike in the volume of waste produced by those who remain, caused by an increase in single-use food packaging. Campuses have also seen recycling contaminated with improperly managed PPE.

The weak financial position of many schools is reflected in the finding that 57% of recycling program leaders who responded to the survey said they were facing operational cuts and 29% were forced to eliminate recycling staff positions. The result has been a chaotic scramble for facilities managers trying to adjust collection arrangements with fewer resources and less predictability of where waste material is accumulating.

Corey Berman from the University of Vermont spoke for many, noting, “Over the years, we created a pretty well-tuned route schedule that avoided unnecessary stops, but the pandemic has thrown that out the window.”

The experience of managers at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill was typical of what many campus recycling program leaders encountered. The school was forced to scramble in March 2020 when the total campus population dropped overnight by 86%, from 40,500 to 5,500. The staff was forced to recalibrate the entire waste collection system on seven occasions over six months, affecting more than 750 service points.

These changes resulted in cutting back trash dumpster service at UNC-Chapel Hill from six to three days a week and cardboard collections from four to just a single day a week. Indoor recycling collections required a similar effort, often based on guessing which buildings were even occupied and in need of service. The repeated efforts to optimize collection services paid off, however, saving $350,000 in reduced services and seeing an approximately 47% reduction in monthly contract expenses.

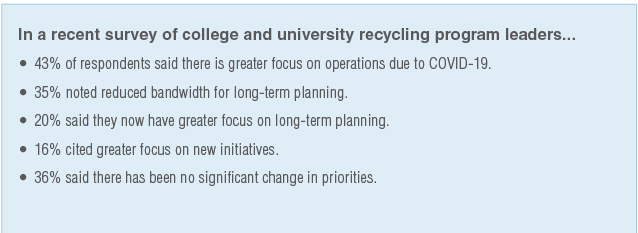

The turmoil of budget cuts and service adjustments, not to mention the scramble to keep front line collection workers safe, has predictably impacted the ability of many program managers to focus on the bigger picture. Asked how COVID-19 had influenced their priorities for the fall term, 43% of survey respondents said they were preoccupied with ongoing operational changes, and 35% said cutbacks were preventing them from focusing on long-term planning.

“Planning and thinking long term is harder now,” said Kimberly Hodge, director of sustainability at Washington and Lee University in Virginia. “It feels more like we’re working in a sort of emergency room, where we only have time/energy to adjust to what is in front of us at the moment.”

On a deeper level, programs that were hamstrung by lack of leadership support before the pandemic have found themselves even lower on the list of administration priorities. The assistant sustainability director for a private college in the Northeast shared the following: “Our facilities department had very limited interest in or creativity around waste management pre-COVID. COVID-related complications, budget cuts, and furloughs have deepened those sentiments. Conversations related to waste have been met with weariness.”

At the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, the pandemic caused the on-campus population to decrease by 86%.

With the pain comes opportunity

However, the survey reveals that despite all the hardship it’s caused, the pandemic is creating opportunities for campus programs in a position to respond.

In recent years, a growing number of schools have begun changing how they collect waste and recyclables from indoor locations. Often referred to as a “centralized” system, the strategy moves away from the traditional network of small waste baskets in favor of having individuals carry their waste items to a small number of centralized bins. In addition to freeing custodial personnel to focus on other tasks, the model can significantly improve recycling rates and contamination.

The survey shows the depth of this trend. Prior to the COVID outbreak, 26% of schools had removed waste baskets from classrooms, and 24% had a hybrid model in place (baskets in classrooms for some parts of campus but not others). Meanwhile, 22% of schools had eliminated deskside service for office locations.

As one example of a COVID-19 silver lining, a significant 21% of the schools that had traditional custodial service at the outset of the pandemic said they had or were actively considering converting as a way to free up custodial labor to focus on cleaning surfaces. In a pandemic, personalized waste service becomes a non-essential luxury.

The pandemic is also creating an opening for upstream waste prevention. A number of respondents said the explosion of disposable food packaging had provided an opening to push dining managers toward implementing reusable to-go container systems. In addition, the years-long effort to wean people from paper files has dramatically accelerated with home-bound staff and faculty cut off from the department printer and inner campus mail system – and there’s a broad expectation that at least some remote learning and office work will remain permanent.

But even for those returning, the experience has changed habits and expectations. As Marty Pool, assistant director of Fort Lewis College’s Environmental Center, commented, “Offices within our college that historically resisted shifting away from paper-only systems had no choice but to rapidly shift to accommodating electronic paperwork. Now that people have gotten used to the new electronic processes, we expect they will remain in place and significantly reduce our reliance on printing.”

Finding a path forward

Finding a path forward

Echoes of the disparity between those programs with strong support and those without could be found in a survey question about program priorities.

Even as many managers cited cutbacks as a barrier to long-term planning, 20% said they were, in fact, focused on long-term operational updates and another 16% were prioritizing new waste reduction / recovery initiatives. With fewer people on campus, this group of respondents noted, time has been freed up to think big.

“COVID has given us space to evaluate our collection system [and] implement efficiencies and allowed us to pursue new diversion opportunities and materials,” said Heather Cashwell, North Carolina State’s waste reduction manager.

Ayodeji Oluwalana, recycling program coordinator at Iowa State University, went further, saying COVID-19 has helped “drive home the need for the university to reduce waste generation.”

Paddy Watson, assistant director for sustainability at Towson University, pointed to a new level of flexibility that could benefit all colleges and universities: “The turmoil of the last year has reset expectations of what’s possible. Especially where they can solve larger problems, there is a new openness to waste reduction ideas that didn’t exist before.”

If the survey reveals a larger message relevant to all recycling managers, it is that wherever there is change there is also opportunity.

Alec Cooley is senior advisor at Busch Systems and can be contacted at [email protected]. Eric Halvarson is program coordinator for the College & University Recycling Coalition (CURC) and can be contacted at [email protected]. BJ Tipton is manager of the Office of Waste Reduction and Recycling at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and can be contacted at [email protected].

Finding a path forward

Finding a path forward