Various factors influence the fees producers must pay in different EPR programs. | meandering images/Shutterstock

The issue of money is never far away from the discussion on producer responsibility policies. For many, their understanding of the policy starts and ends with the annual invoice they receive. It is simple to characterize these costs as a government tax and not pay it more heed than that; however, as discussed in our previous article, not all producer responsibility models are the same. The manner in which policies are established impacts costs and how they are assigned.

What determines costs

The costs related to producer responsibility are generally determined by the following factors:

- Whether the policy is a shared responsibility or a full producer model (as discussed in our last article). In the shared responsibility model, generally producers have no control over the operational decisions (e.g., collection, processing) that generate costs. Instead they pay a percentage of the cost incurred by local governments. In a full producer responsibility model, producers have the direct ability to influence operational decisions – more so if that producer responsibility model allows for competition.

- What and who is obligated. Costs are also impacted by what products and/or packaging is designated and what exemptions may be provided. Many producer responsibility regulations exempt businesses under a certain size or that supply under a certain weight of material into the market. This often makes sense as it helps to reduce administrative costs; however, the obligated producers potentially have to pay more for the management of these stranded materials. The issues of stranded materials can also occur if the obligated products are not inclusive. In many Canadian provinces, packaging is included (e.g., aluminum plates sold with a store-bought pie) but products are not (e.g., aluminum plates bought as a product). Both contribute to curbside recycling programs but only one set of producers is required to ensure they are properly managed. Similar issues can also be created when indiscriminate lines are drawn when only residential materials are captured (i.e., how does one know whether a pop can was consumed in a residential setting or not?).

- How strict collection and management targets are. The stringency of collection and management (e.g., reuse, recycling, recovery) targets and the liability associated with meeting them directly correlates to efforts and resources necessary to achieve them.

- The degree of prescriptiveness of the outcomes established by the government. How outcomes are established in the policy has a direct impact on system costs. Some producer responsibility policies have more specific requirements about how results should be achieved (e.g., collection, R&D, litter management, education). These requirements will be discussed further in the next article.

- The structure of oversight and enforcement. Some regulatory systems, such as British Columbia’s, use taxpayer funds to provide oversight. Others, such as Ontario and Quebec, allocate a fee on producers. More details on enforcement will be explored in the last article of the series.

How costs are allocated

Whatever the structure of the policy, producers generally tend to organize themselves in one or multiple producer responsibility organizations (PRO). The PRO or PROs then must find a way to meet the requirements established by the policy and allocate systems costs to their members.

From collection to material sale, recovery involves many different activities. The cost varies from one material or type of product/packaging to another because:

- Volumes differ. For example, there is much more cardboard boxes than PET trays in terms of weight;

- Equipment is designed for specific materials and the capital cost can be assigned specifically to those materials (e.g., eddy current for aluminum);

- Product characteristics could be more or less detrimental or costly (e.g., for the same weight, plastic bales require more space than paper bales);

- Revenues are different (a ton of paper is worth less than a ton of PET).

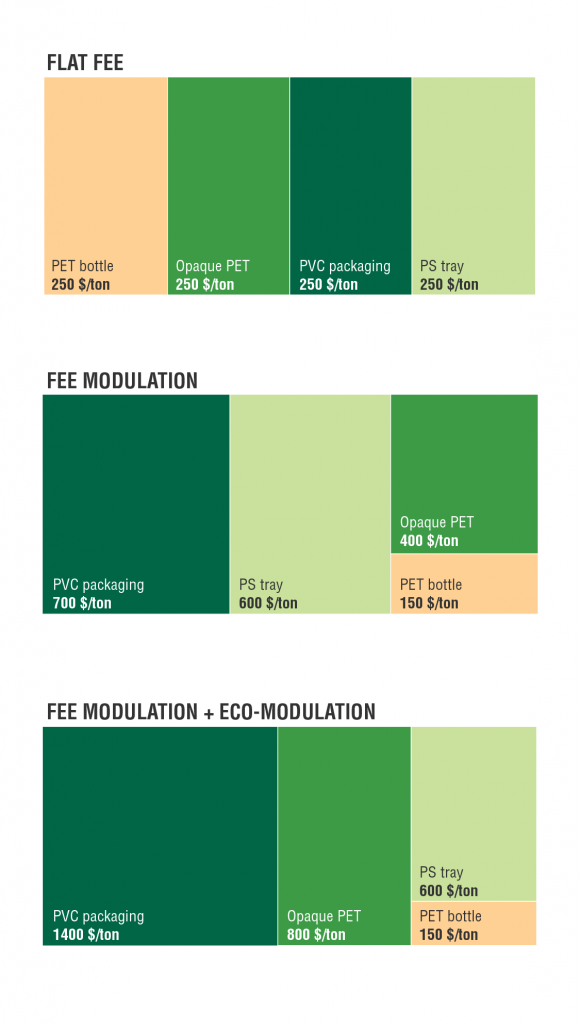

A PRO or PROs generally allocate costs based on three main methodologies. The below figure gives a fictional example of how each methodology impacts contributions by material.

A flat fee structure is where fees are applied broadly and are not differentiated in any substantive manner based on the actual cost to manage various product or packaging formats. An example could be to treat all plastic packaging under the same fee structure, despite certain plastics being easier to collect and sort and having a higher commodity value.

Fee modulation is where fee determination is more granular in nature, with different categories for different formats and materials. In Canada, most extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs modulate fees based on activity-based costing (ABC) evaluation to determine the financial impact of each material on the system, although other financial methods are being explored now. ABC consists of breaking down every activity and assigning a general cost based on capital and operational expenditures.

Fee modulation is representative of the costs associated with the targets that are set. If targets are low and are broad based (e.g., one target for all plastic packaging), efforts do not need to be undertaken to address more difficult-to-recycle materials. This is currently the case for all packaging producer responsibility policies in Canada. PROs charge slightly higher fees for these materials but they are essentially allowed to hide – less attention is paid to collect them and to find solutions to ensure they are properly recycled, as for polystyrene products or multi-laminated packaging.

If the targets were more specific and set higher, producers would need to improve collection and drive markets for these materials, and fees would better represent real costs. As Usman Valiante noted in a recent paper for the Recycling Council of Alberta, in programs where targets are low and lack specificity, these fees basically become a marginal packaging tax.

Eco-modulation is where fees are adjusted to further incentivize design changes, such as those to improve recyclability, promote recycled content or encourage reuse. Eco-modulation is based on a reward and/or penalty approach.

Eco-modulated fees are increasingly popular, because they try to directly enhance the sustainability of packaging with financial measures. Usually, eco-modulated fees are calculated on top of the modulated fees.

France has probably the most ambitious system that includes benefits for efforts related to recyclability labeling on packaging (similar to the How2Recycle label), material reduction and use of recycled content.

The policies also can include penalties associated with the use of problematic components or additives that are detrimental to product recycling. For example, in order to discourage the usage of opaque PET and PVC packaging, the penalty is a 100% increase in fees.

Implementation of eco-modulated fees requires a high level of understanding of the current recovery and recycling value chain, and also a great control of how materials are collected, sorted and recycled. Factors such as the following must be taken into consideration:

- Is the magnitude of modulation high enough to influence producer or consumer decisions (e.g., relative scale based on the cost of the product)?

- Is the magnitude of the fee so high that it discourages innovation or system changes that could address the issue (e.g., artificial intelligence and automation)?

- If there are competing PROs, how can a consistent eco-modulation be applied?

Some critics argue, however, that eco-modulation is unnecessary if high specific targets were appropriately set and companies were liable to meet them. There can also be concerns about competition/fairness issues based on how fees are eco-modulated.

It is an interesting question as to whether advocacy against high targets and full producer responsibility may be directly leading to higher costs for producers by requiring them to pay for costs they have little ability to influence in shared responsibility models and by forcing governments to intervene in other ways to drive outcomes. Additionally, they may be forced to pay higher costs because of other added requirements (e.g., promotion and education, research and development, collection requirements) and because of the establishment of eco-modulated fees and parallel recovery programs, such as deposit systems.

Once again, the manner in which policies are established impacts costs and how they are assigned. However, the overall target of those policies should remain to ensure products and packaging are properly collected and managed. How targets are established and evaluated will be the subject of the next article.

Pierre Benabidès is from Lichens Recyclability, Sara-Emmanuelle Dubois is from NovAxia Inc. and Peter Hargreave is from Policy Integrity Inc.