Every year municipal crews in Los Angeles collect 1.5 million tons of material.

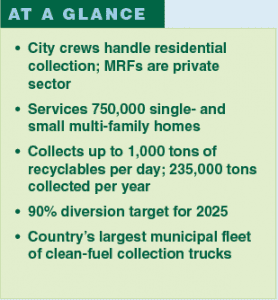

The second-largest city in the country also has a very ambitious waste diversion goal: 90% by 2025. That means Los Angeles must stay creative to continue managing the massive volume of recyclables its residents generate.

“We have a vast amount of bins all throughout the city,” said Robert Potter, city of Los Angeles division manager for the Bureau of Sanitation. “There are roughly 3 million containers that are out there on any given week.”

The city’s residential recycling program relies on city crews to service 750,000 single- and multi-family homes.

Every day, the city collects 3,600 tons of garbage, 1,600 tons of organics and about 1,000 tons of recyclables. That equals out to 1.5 million tons of overall material per year, Potter said, and about 235,000 tons of recyclables in a year.

And like most municipalities, particularly those in California, Los Angeles has faced challenges stemming from the wider recycling market slump that has occured in the wake of China’s National Sword policy.

“Our recycling program has seen a shift … in being a revenue stream to a little bit of a cost center,” Potter explained.

Shifts in MRF contracts

California has aggressive diversion goals that municipalities must meet. And as a major metropolis, Los Angeles (population: 4 million) can’t exactly discontinue service or temporarily scale back collection of certain materials as nimbly as a smaller municipality.

To respond to the challenges and ensure the recycling program is sustainable amid the new market realities, the city and its private-sector MRF contractors that receive residential recyclables have changed some of their contractual terms.

“When we had conversations with our MRFs, we said, ‘You know what, this minimum floor price, this set dollar amount for a five-year period, it just can’t work anymore,’” Potter said. In short, the city understood it could no longer reasonably expect to receive at least $10 per ton for the duration of a contract.

During the recent contract negotiations, the city and MRFs came to an agreement on a shifting floor system. Under the new contract, the markets for three key commodities are evaluated every three months, with a pricing formula determining whether the municipality pays or receives revenue for that time period.

During the recent contract negotiations, the city and MRFs came to an agreement on a shifting floor system. Under the new contract, the markets for three key commodities are evaluated every three months, with a pricing formula determining whether the municipality pays or receives revenue for that time period.

The underlying idea is that when markets are strong and commodities are way up, both parties benefit, but when the market tanks, both parties absorb the hit.

“It’s not perfect,” Potter acknowledged, noting that the markets became even more volatile as the city’s contract negotiations were underway and that there is room for further improvement. But in the bigger picture, the arrangement means MRFs can stay in business without getting hit with huge revenue declines.

During the negotiation process, the city addressed several key questions: What are the values for commodities, which are the primary commodities, and is it possible to set a minimum floor value based on the markets?

“That’s a true reflection of what’s going to happen to the MRF and what’s going to affect us financially,” Potter said.

Exploring alternatives

Potter acknowledged that reaching the city’s 90% diversion goal within six years will be “challenging in the current environment.”

In April, the Los Angeles City Council voted to direct the Sanitation Bureau to develop a report exploring the wider impact China’s import restrictions have had on recycling efforts in the city.

“The city’s … program was designed to effectively manage solid resources collection and allow the city to achieve zero waste goals,” the Council directive stated. “The program’s recycling objectives were tied to the purchase of recyclable materials by Chinese firms.”

The recycling crisis, the City Council document continued, presents an opportunity for Los Angeles to rethink its waste system. First and foremost, the city could shift toward a waste reduction approach by considering bans of not-currently-recycled products.

The Council referenced a recent product ban proposal in Berkeley, Calif., which would prohibit all single-use disposable foodware inside restaurants and charge a 25-cent fee per beverage or meal that is served in packaging. The Berkeley ordinance would also require that the “disposable” packaging be recyclable or compostable.

The report the Sanitation Bureau has been asked to prepare will explore alternative approaches the city can take to push toward its waste management goals. This includes “setting ambitious and achievable source reduction goals for single-use food and beverage packaging” and other “highly-littered and non-essential” plastic products. The report will also look into local and regional market development as well as tactics to support reuse projects.

Other areas of focus

Los Angeles has also been active in optimizing its truck fleet and finding ways to move the needle outside the residential sphere.

The city has six different “wastesheds,” each of which has 150 collection trucks.

Los Angeles operates the largest clean-fuel fleet of collection trucks of any municipality in the country, Potter said. And the city is currently working to move toward electric collection vehicle use.

Meanwhile, the city is planning for the future through a Solid Waste Integration Resource Plan (SWIRP), which Potter said “targets all the elements of municipal waste, ensuring we can divert the highest percentage possible.”

It was the SWIRP that set the 90% diversion goal. And through the plan, the city also formed a public-private partnership called recycLA, which was launched in 2017 and made changes to commercial and multi-family collection services. Among other components, the program introduced commercial franchise zones.

Think your local program should be featured in this space? Send a note to [email protected].

This article originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.