This article appeared in the March 2019 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

We have all heard plenty about China’s Green Fence and National Sword. The policies have led to tight quality standards, limited import licenses, strict inspections – and major market disruptions.

The shake-up is causing such concern in the North America recycling market because, over many years, we all got comfortable with strong demand for mixed paper and plastics and high tolerance for contamination across the board. Collection programs expanded and converted to carted single-stream systems, and the private sector developed materials recovery facilities (MRFs) in line with those trends. To win recycling service contracts, some companies chose not to bid the actual expense of collection and processing, anticipating that their portion of the revenue share would be sufficient to cover costs.

Now, as materials like mixed paper are at historic price lows, the two sides in recycling public-private partnerships (PPPs) – private MRF operators/haulers and the communities they serve – are encountering problems as they attempt to adjust. Simply put, our recycling PPPs are out of sync and need a reset.

If history can be our guide, markets will go up … and markets will go down. And this phenomenon will play out again and again and again. How do we stay the course regardless of the challenges encountered along the trail?

Material values collide with recycling policy

To put this question in context, let’s consider the concepts of “value-driven” and “policy-driven” recycling. Recycling was originally sparked by the intrinsic value of materials – for example, scrap metals and cardboard – that could economically be recovered from large-volume generators. Value-driven recycling shapes much of the structure, supply, demand, price dynamics and recovery rates of “traditional” recycling.

Since the 1970s, however, recycling in the U.S. and worldwide has grown in response to environmental and resource-management factors. We refer to this as policy-driven recycling, where the materials recovery programs undertaken by municipalities and businesses are driven primarily by goals, mandates, bans and other mechanisms in addition to avoided disposal costs. Supply does not readily ramp up or dwindle down in response to changing markets. Looking forward, we can only imagine where and how policy will evolve. Examples might include more packaging bans, zero waste goals, material innovations, material scarcities and producer responsibility.

How do we reconcile the realities of policy-driven and value-driven recycling? We recommend keeping four points in mind:

- Recovered materials are commodities, meaning their values fluctuate.

- Recycling has costs, particularly in the areas of collection, processing, transport and marketing.

- Each recycling program (and the material mix it takes in) is unique.

- All MRFs are not created equal, with variations seen in age, type, equipment and operations.

Much of the challenge recycling PPPs face boils down to these four factors and how the risks, rewards and responsibilities are allocated between the public and private players. In the following sections, we’ll highlight key issues associated with each point.

Recovered materials are commodities

Markets for recyclables are well-established and respond to the laws of supply and demand (think other commodities such as grains and oil).

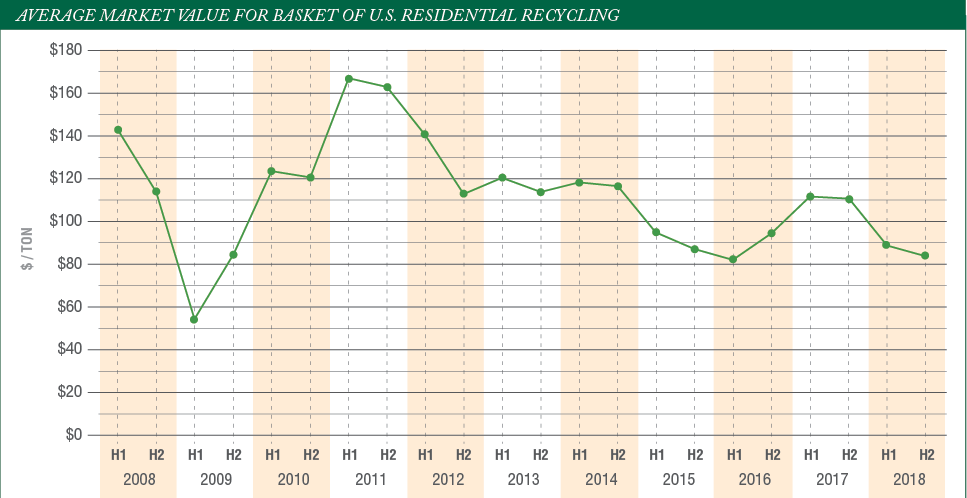

Market highs and lows in recycling have been relatively short-lived, and over time average prices have stayed within relatively narrow ranges for each commodity. The graph below shows the average market value (AMV) for a typical basket of residential recyclables over the past 10 years. The graph shows periods of fluctuations but also demonstrates that, in general, the AMV has remained between $80 to $120 per ton.

Most every recycling PPP is trying to navigate major changes in its financial terms for processing fees and revenue sharing. Unfortunately, right now there isn’t full transparency regarding recycling cost and revenue drivers, which has resulted in a disconnect between the public and private sectors. Some private MRFs, for example, are proposing terms that make recycling financially unsustainable for communities as the MRFs seek to minimize risk and lock in favorable terms in a “down” market.

Developing recycling PPPs that understand true processing costs and are responsive to both “down” markets and “up” markets will help to mitigate the unequal allocation of risks and rewards over time.

Recycling has costs

As PPPs attempt to find their footing today, stakeholders on each side must consider the entire cost for recycling – from collection to processing to marketing. Recycling should not be viewed as only a source of revenue because all services, including processing, have a cost. Revenue from selling recyclables may or may not offset all of the processing cost.

Municipal programs need to be prepared to pay for processing of recyclable materials and consider that the revenue from commodity sales may or may not offset that cost depending on material values.

Further, for recycling PPPs to be sustainable, they need to be based on transparency, collaboration and a common understanding of economics across the recovery chain. MRFs are certainly due full compensation for the cost to develop, operate and upgrade their sites, provided that those investments are truly made to keep up with state-of-the-art technologies and market standards. At the same time, communities are certainly due compensation for the raw materials they deliver to MRFs independent of the cost to convert them to commodities. As shown in the graph above, the blend of residential recyclables has always had value, and it still does.

Recycling PPPs need to acknowledge not just the financial terms of services, but also the cost and revenue factors that are outside local control (commodity markets, composition and technological innovation). Partnerships will benefit both sides when they are built on a foundation of economic transparency, and when they integrate mechanisms for managing and adjusting across the course of a contract.

Every program is unique

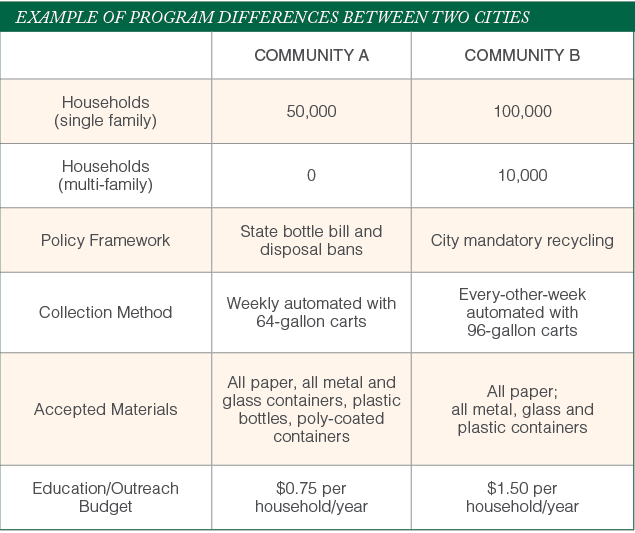

When it comes to sizing up recycling programs in different areas, an apples-to-apples comparison rarely exists, so cookie-cutter approaches to recycling PPPs don’t work very well. In short, all solid waste is local.

The table above shows recycling specifics of two hypothetical communities, illustrating some of the ways that local programs can differ.

Why do such differences exist, even among communities in the same region? To start, recycling programs individually define what materials are accepted. And from there, the quality and frequency of education and outreach has a significant effect on participation, compliance and composition. In addition, local recycling mandates and/or disposal bans affect recovery and composition. For example, communities in bottle-bill states can have less glass and aluminum in their curbside recyclables.

At the same time, different processors do not always accept the same materials, and that fact will impact what nearby community programs look like. Local and regional markets for commodities, or the lack thereof, may drive a processor’s business model for certain commodities. For instance, in a community where there is not a regional market for glass cullet, processors might not want to include glass as an accepted material because it costs more to process and transport than the value of the recovered commodity.

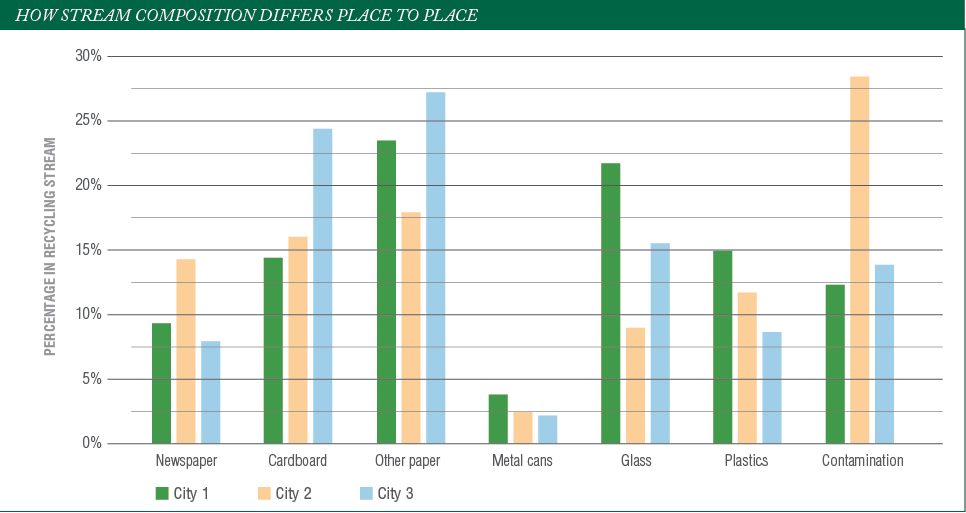

Finally, the composition of the recycling mix in different communities is rarely the same. Composition is affected by policy (bottle bills, mandates and bans, for example) and program design (designated materials, collection method, and education and outreach campaigns). Other factors, such as community demographics and regional consumption patterns, also affect composition.

The graph below shows the dramatic differences in recycling composition of three actual neighboring cities (the market value of recyclables is based on January 2019 commodity indices and contamination at $0 per ton value). On cardboard, for example, City 3 (in blue) sees 71 percent more in the stream than City 1 (green). City 1, meanwhile, has a stream that contains 142 percent more glass than the stream in City 2.

Meanwhile, composition across the board will continue to change over time, a fact driven by a number of trends, including: conversion from print to digital media, the growth of online shopping and home delivery, lightweighting of packaging, and conversions to multi-layered flexible packaging.

Not all MRFs are created equal

The final principle that must be understood to develop sound PPPs is rooted in the fact that MRF technologies continue to evolve rapidly. In the old days, facilities relied on manual sort lines, and over time they added disc screens, ballistic separators, optical separators and more. Now, in some plants, we are starting to see robotic pick stations with artificial intelligence.

In addition, local market specifications may dictate additional processing requirements. For example, glass cleaning systems are often customized to local market demand, whether that be civil applications (engineered drainage media, for example), beneficiation, or direct sale to manufacturers.

MRFs operating today vary greatly in the age, type and level of mechanical technologies they use to separate recyclables. And the technologies employed significantly impact operational effectiveness and financial performance.

MRFs with older technologies have limited flexibility and adaptability to respond to commodity markets. Many have been retrofitted to keep up with changing composition as well as to help reduce labor costs, increase throughput and adapt to commodity markets (see the feature story on page 44 for a rundown of recent upgrades). However, the effectiveness of a retrofitted MRF is often dependent on the amount of capital and how well the equipment integrated.

“Franken-MRFs” are those that have been cobbled together over the years and might not work very well. “Zombie-MRFs” have already died but somehow continue to operate. Both can be susceptible to higher-than-normal residue levels due to low material recovery rates in the plant – essentially, recyclables are ending up in the residue that’s disposed – and higher-than-average operating costs.

Just as materials evolve over time, MRFs need to evolve as well. MRFs using old equipment cannot be expected to run cost-effectively and produce the necessary quality. A sustainable MRF business model needs to include allowances for technical upgrades as the material stream and markets change.

A future for public-private recycling

If driven strictly by financial implications, recycling programs would only exist when it costs less to recycle than to dispose. However, broad societal and environmental benefits exist that cannot be fully reflected in dollars and cents. How do we, the recycling community, address the complexities of policy-driven recycling in a market that ultimately must be both economically and environmentally sustainable?

State, regional and national initiatives are certainly part of the solution, including investment in recycling market development. But such broad frameworks are beyond the realm of what can be achieved at the local level through recycling PPPs. At the local level, recycling programs should be based on clearly established community goals and objectives, backed by policy and programs, and coupled with contractual provisions that help to monitor and control elements that drive costs.

For recycling PPPs to be sustainable, they need to be based on good communication, clear agreements and collaboration to manage the different pressures on commodity markets and processing costs. They need to integrate mechanisms for managing and adjusting to technological innovations, market conditions and program evolution over the course of a contract.

In particular, stakeholders need to establish contracts for processing services that are transparent and flexible to share risk and reward. For example, a commodity market index-based revenue share allows both parties to benefit when the markets are up and share the risk when markets are down. In addition, a community and its private processor should both benefit from investing in education and enforcement that successfully reduces contamination and increases recovery. Likewise, we need to develop forward-looking contracts that incentivize investments in new technologies capable of increasing efficiency and quality.

These partnerships require the underpinnings of regular composition studies to identify changes in generation and packaging, as well as consistent monitoring of levels and types of contamination. Kessler Consulting, Inc. has conducted dozens of these recently and the range of variation is significant, underscoring the need for local data.

Further, contracts between partners must contain a framework that describes the process, addresses potential failures in the process, clearly defines roles and responsibilities, and assigns accountability for each step.

Developing successful and sustainable recycling PPPs is complicated and must be customized to each locality and community. Only through clear, honest and open communication can we work through solutions that will share reward, mitigate risk and remain flexible.

With these types of arrangements in place, we may be able to get back in sync and reset the relationships between public and private partners for the future. When stakeholders walk the recycling path together, everyone stands to gain.

Mitch Kessler, principal at Kessler Consulting Inc. (KCI), is a nationally recognized expert in the procurement and operations of solid waste collection systems and materials recovery programs and facilities. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Peter Engel, project manager at Kessler Consulting Inc., has worked with domestic and international clients to implement recycling, composting and integrated materials management systems since 1987. He can be contacted at [email protected]. Kessler and Engel have worked together since 1988.

KCI is a leader in solid waste management planning and program implementation. Since 1988, the company has provided practical and innovative consulting services to more than 250 public- and private-sector clients.