This article originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Resource Recycling magazine. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The Whitewater forest fire in Oregon’s Cascade range last summer was among the most impactful in the Northwest in 2017, eventually spanning 11,500 acres and costing nearly $40 million to fight. It also unmistakably altered the landscape around some iconic Oregon hiking trails.

But while the blaze itself wreaked economic and environmental havoc, the process to control it did come with a notable silver lining: a recycling pilot project aimed at reducing tonnages sent to disposal by firefighting crews and support teams.

The initiative at the U.S. Forest Service’s incident command post near Sisters, Ore. brought together federal fire employees and a private Oregon firm that specializes in waste diversion at events. Together, stakeholders were able to streamline collection, sortation and logistics in an environment where safety and speed – not materials diversion – are generally top of mind.

The project reported an overall 48 percent landfill diversion rate, and it provided a starting point to move the needle on waste management best practices at other temporary government sites.

The initiative also proves that with planning and procedures, materials collection can be incorporated into nearly any environment.

As a fire grows, so does waste generation

A lightning strike in a remote section of Oregon’s Willamette National Forest on July 23, 2017 caused what would eventually become the Whitewater fire. As the blaze grew, the Forest Service established an incident command post (ICP) at the Hoodoo Ski Resort near the mountain town of Sisters, which is about 25 miles from the city of Bend. This site served as the main camp where the incident management team was stationed.

A helicopter base was established around 10 miles from the ICP to support fire-fighting air operations. And as the fire spread further, two satellite locations, or “spike camps,” were set up to more easily supply firefighting resources to specific areas. In all, more than 600 personnel were spread across these different sites, and waste generation was a natural byproduct of the effort as workers consumed high volumes of bottled water, ate meals prepared by a catering staff, and leveraged supplies that often came in corrugated boxes and other packaging forms.

But while the Forest Service mobilized its people and equipment, it was also taking action bring in reinforcements on the materials recovery front.

Managers from the government agency in 2016 had worked with a Bend-based company called The Broomsmen that specializes in providing recycling and cleanup services for weddings, concerts and other gatherings. The idea was to create a plan of action for streamlining recycling at forest fire camps, and as activity around the Whitewater incident grew, the partners launched their pilot initiative.

Leaders from The Broomsmen had in 2016 started a separate business called Triple Flare Recycling, and that operation was hired by the Forest Service to establish a program for recovering materials at the Hoodoo ICP and associated locations. The team arrived at Hoodoo on Aug. 15 and spent 41 consecutive days working to manage waste from crews battling the Whitewater fire as well as a second blaze, the Horse Creek Complex fire, both of which were located in Willamette National Forest.

Upon arrival at the ICP, the Triple Flare team encountered a rudimentary waste and recycling system that consisted of trash cans adorned with handwritten signage. Recycling was available at eight locations throughout the camp, but placement was sporadic. There was no standardized color/label system place, and signs appeared in English only.

Further, no commingled recycling infrastructure was observed, and the food caterer supplying meals to firefighters was not targeting any materials for recovery beyond OCC and cooking oil. Overall materials diversion was estimated to be 20 percent, and that consisted mostly of OCC.

Building out the infrastructure

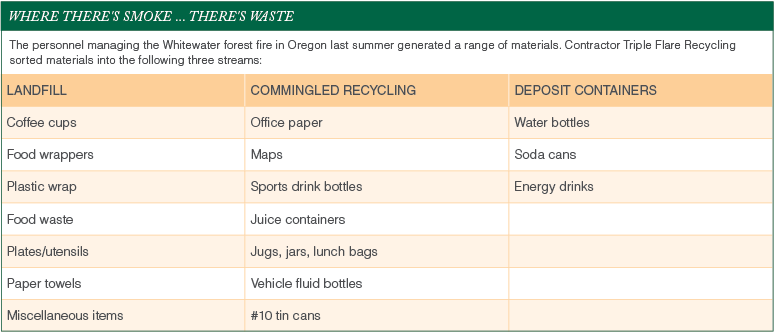

Representatives from Triple Flare first assessed the stream of materials being generated by crewmembers and determined what was recoverable (see chart) and what should be sent to disposal.

One important finding was that large volumes of water bottles, soda cans, energy drinks and other containers covered by Oregon’s bottle deposit program were being generated by firefighters who depended on such products for hydration (and to stay alert amid long shifts). The value of each Oregon deposit container had increased to 10 cents in April 2017, so it was clear that isolating these bottles and cans for redemption could have significant economic repercussions for the operation’s waste management budget.

To begin building a stronger materials recovery infrastructure, the Triple Flare team set up a system of waste stations in which well-marked recycling and garbage receptacles were placed together. More than 35 of these custom-constructed stations were established across the ICP, the heli-base and at spike camps. A two-man maintenance team from Triple Flare managed these stations daily.

Supply trucks would arrive to the ICP throughout the day with materials and equipment to support the firefighting operation. The Forest Service utilizes a system through which all the supplies needed at camps (tents, chainsaws, hoses and more) are transported from the agency’s “cache” warehouse near Bend. After trucks dropped their load, the empty vehicles were used to bring recycling back to the cache, and from there, materials could be moved to proper recycling channels.

An emphasis on communication and organization helped the Whitewater firefighting crew capture the many plastic beverage containers being used in the field.

Meanwhile, when trucks serviced spike camps, they would backhaul waste to dumpsters located at the ICP. These loads typically contained a mixture of trash and recyclables, so the Triple Flare team used signage to direct drivers to offload in front of the dumpsters, giving team members the opportunity to sort material. Over 50 percent of spike camp material was observed to be recyclable.

While roughly 75 percent of waste generated by the firefighting unit occurred at the established camps, the other quarter came as firefighters worked out in the field. And a good portion of this material was plastic bottles and other valuable recyclables. To address this issue, a color-coded bag system was used to help firefighters sort water bottles from other trash while undertaking their important work.

Orange bags were distributed to firefighters with instructions that they should be used for bottles and cans only. And clear bags were used for all other field waste – this allowed garbage sorters back at camp to easily see when recyclable material was being mixed in with discards.

Though the pilot effort focused only on diverting recyclables, project leaders did observe a significant amount of organic material ending up in the waste stream, especially at the catering and spike camp operations. If that material were specifically targeted via camp recycling systems in the future, total diversion rates could exceed 70 percent.

Reporting results and looking ahead

A formal waste audit was performed every four to five days of camp operation. This was an important measurement step that allowed project leaders to track progress and tweak the recycling infrastructure on the fly.

The overall numbers tallied through those audits show that the landfill diversion rate across the 41 days of the initiative was 48 percent. Below are recovery totals for specific material types:

- 105,000 beverage bottles, which amounted to a redemption value of $8,000 credited back to the Forest Service.

- 220 yards (roughly 11,000 pounds) of OCC.

- 30 yards (roughly 10,900 pounds) of mixed office paper.

- 200 gallons of cooking oil.

The Triple Flare effort also helped the camp more efficiently use dumpster space, a fact that had clear cost benefits. Typical costs for emptying a dumpster in these environments can be in excess of $300, depending on location, hauling fees and landfill tip fees. Packing dumpsters to maximum capacity is a clear best practice.

One example on increasing this efficiency: Unflattened corrugated boxes were regularly making their way into landfill dumpsters at the start of the pilot initiative. This practice was consuming valuable space, causing recyclable material to get landfilled and increasing overall costs.

In addition, the team helped the operation better use dumpsters that were put in place for recycling collection. At one of the spike camps, for instance, a 20-yard receptacle that was supposed to be used for recoverable materials was actually containing high levels of garbage. Without the better labeling and sorting brought by the Triple Flare team, this dumpster would have been relegated to landfill, negating all field recycling efforts.

The overall effectiveness of the pilot program has led stakeholders to expand the materials recovery program during the upcoming forest fire season.

After spending the winter working alongside recycling industry stakeholders to present the Whitewater camp results to government officials, the Triple Flare team is now able to be deployed to Forest Service sites in Arizona, Oregon, New Mexico and Washington.

Phil Torchio is the founder of Triple Flare Recycling and event recycling company The Broomsmen. He can be contacted at [email protected].