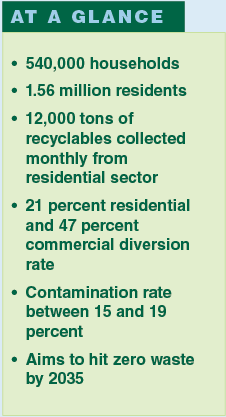

In a city where city collection crews service 540,000 households, thinking big is the norm. That became abundantly clear when the city of Philadelphia announced its plan to send nothing to disposal by 2035.

In a city where city collection crews service 540,000 households, thinking big is the norm. That became abundantly clear when the city of Philadelphia announced its plan to send nothing to disposal by 2035.

It’s the latest and most ambitious goal for the City of Brotherly Love, which has been recycling for more than 30 years, thanks to community interest that predates Pennsylvania’s statewide recycling requirements.

“Philadelphia has a very active advocacy history for recycling, and the city has certainly benefited from that,” said Marisa Lau, acting recycling coordinator.

The city now has an action plan solidified by a mayoral executive order, and a government committee is charged with making zero waste happen. City officials credit its progress to committed elected officials and efforts to bring together a variety of interest groups.

Program evolution

Pennsylvania’s State Recycling Act 101 passed in 1988, requiring certain communities to have recycling programs in place, based on population and density. But Philadelphia had been recycling for some time before the mandate, collecting newspaper through a curbside program since 1984.

Mandates and legislation have backed that advocacy up with statutory requirements over the years, pushing the city’s recycling initiatives forward. Commercial properties, for example, have been statutorily required to recycle at least the same materials as residents since 1994. And municipal buildings have been required to recycle since 1996.

Mandates and legislation have backed that advocacy up with statutory requirements over the years, pushing the city’s recycling initiatives forward. Commercial properties, for example, have been statutorily required to recycle at least the same materials as residents since 1994. And municipal buildings have been required to recycle since 1996.

In 2009, the city fully adopted weekly, single-stream recycling collection, which had been phased in over several years. The program has gradually accepted more materials over the years, most recently adding aluminum and steel baking tins and aluminum foil. Currently, the program accepts paper, cardboard, newsprint, aluminum containers, tin/steel/bimetal containers, plastic food and beverage containers and packaging, aseptic cartons and packaging, and glass.

Philadelphia has a residential diversion rate of roughly 21 percent. Its commercial rate, not including C&D materials, is about 47 percent. The commercial sector generates about three-quarters of the material in the waste stream.

Combining residential and commercial, the city states its citywide diversion rate is about 37 percent.

City crews collect residential recycling, and commercial is handled by the private sector. The city owns a transfer station and the recycling collection trucks. Currently, the city contracts with a Republic Services MRF for materials processing.

Philadelphia city crews service 540,000 residential households. A minor portion of that is small businesses that are eligible for city collection, and city routes also include small multi-family properties of up to six units. But the majority is single-family residential homes.

Public works crews collect about 12,000 tons of recyclables per month. The material has a contamination rate that ranges between 15 and 19 percent. For single-family homes, recycling is funded through taxes without any extra fees, and households are automatically enrolled in recycling collection service.

Philadelphia recently completed a waste characterization study, which was carried out throughout 2017. The study provided a number of details that would guide future diversion planning. For instance, it showed that 30 percent of the city’s waste stream was organics.

“It kind of confirmed what we were thinking – it’s not possible for us to get to zero waste just by increasing our recycling rate,” Lau said. “It’s going to take waste reduction, and adding new materials to the program.”

The plan to propel diversion

Communities statewide in Pennsylvania are required to strive for 35 percent diversion, and Philadelphia has had a 50 percent goal for years. But in 2016, the city officially set its goal as zero waste by 2035, and formed an action plan of steps it will take to get there.

To hit zero waste, the city plans to reduce its waste generation and increase diversion to 90 percent through recycling and composting. The remaining 10 percent of waste material would be sent to waste-to-energy operations.

That’s going to take work on a number of fronts. City-owned buildings will begin a new reporting process to track progress toward waste reduction. The city also began requiring special events to provide recycling service. The program provides city volunteers to help attendees sort their waste at these public events.

In addition, Philadelphia has a longstanding recycling rewards program run by Recyclebank.

“The key is that they’re not just rewarding people for recycling at home – they’re able to reward them for a whole range of zero waste actions, which includes volunteering at these zero waste events,” Lau said.

Connecting waste and litter

The current zero waste action plan is tied closely to the city’s top elected official.

While campaigning, Philadelphia Mayor James Kenney made a pledge to find a solution to the city’s “historic and seemingly intractable litter problem,” explained Nic Esposito, director of the zero waste and litter program.

While campaigning, Philadelphia Mayor James Kenney made a pledge to find a solution to the city’s “historic and seemingly intractable litter problem,” explained Nic Esposito, director of the zero waste and litter program.

“When [the mayor] studied the issue, he didn’t see waste and litter as two separate issues,” Esposito said. The goal was to shift waste management practices as a whole, rather than only step up litter cleanup efforts.

“He knew that a very ambitious goal like zero waste would not be taken seriously or even work when the city streets look the way they do,” Esposito said.

Esposito credits the successful development of the zero waste plan to strong community organizing and pairing waste management improvements with litter cleanup efforts.

“Not every department or community stakeholder is going to care about waste, but when you can show them how better waste management practices will help reduce litter – which they do care about – then you’ve got them,” Esposito said.

This article originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Think your local program should be featured in this space? Send a note to [email protected].