A mixture of urban, suburban and rural communities can create substantial challenges for a municipal recycling program that includes them all.

A mixture of urban, suburban and rural communities can create substantial challenges for a municipal recycling program that includes them all.

For Prince George’s County in Maryland, those challenges have been met and overcome with aggressive recycling goals and steady improvements through the years.

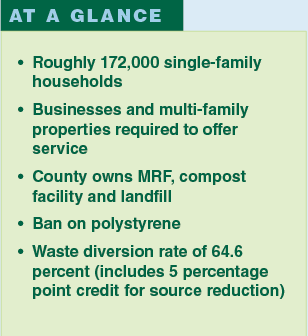

Prince George’s County has 900,000 residents, making it Maryland’s second-most-populous county, but it is the top performing county in the state when it comes to recycling and waste diversion. The county is home to about 172,000 single-family households and stretches across 500 square miles. The county owns much of its resource recovery infrastructure, including a materials recovery facility, composting facility and municipal landfill.

Each year the county processes more than 40,000 tons of recyclables at its MRF, and the county in 2015 notched a 59.6 percent recycling rate, according to a report from the Maryland Department of the Environment. That figure includes glass, metals, paper, plastic, compost and several miscellaneous materials, but it does not include C&D or land-clearing debris.

The state also gives counties additional credit for source reduction activities. Prince George’s County earned a 5 percentage point increase to its recycling rate based on voluntary reporting of source reduction efforts, meaning it ended up with an official waste diversion rate of 64.6 percent in 2015.

It’s an impressive figure, at nearly double the national recycling rate, but the county plans to keep pushing.

It’s an impressive figure, at nearly double the national recycling rate, but the county plans to keep pushing.

“We don’t want to plateau where we are,” said Adam Ortiz, the county’s director for the department of the environment. “There is still a lot of recoverable material that is going into the landfill.”

Three decades of development

The county didn’t get to 60 percent diversion overnight. Its robust residential recycling program has been operating for more than 30 years, one of the first official programs in Maryland. Recycling activities date back further than that, but in 1988 the county initiated its first government-run collection programs in five of its communities.

A county-operated dual-stream MRF opened in 1993 concurrent with source-separation curbside residential recycling. The MRF was converted to a single-stream facility in 2007, and the next hauler contract was bid for single-stream collection with larger 65-gallon receptacles. The new facility allowed the county to accept a variety of new materials, including plastics Nos. 3-7. In 2016, the county switched from twice-weekly to once-a-week garbage collection, with recycling collected the same day as trash.

County officials cite these shifts as influencing a large increase in diversion.

“The combination of single-stream recycling and the larger sized recycling receptacles have had the positive result of raising the residential recycling participation rate by 41 percent,” according to the county’s recently updated 10-year solid waste plan, a document that’s required by state law.

The county places emphasis on outreach and education. Ortiz said representatives attend more than 250 outreach events per year and also engage with the community through social media, directing residents to an online recycling information toolkit.

Prince George’s County has also implemented bans on certain materials that it found problematic for recycling efforts. It joined neighboring Montgomery County and Washington, D.C. in enacting a polystyrene ban in 2016. Ortiz said there was some initial pushback but that there has been a lot of partnership from businesses with the ban.

In another case, the county was having problems with yard debris arriving at the compost facility in plastic bags. So, in 2014, the county stopped accepting compost in plastic bags at its facility, instead advising residents to use paper bags or to collect it loosely.

“That has been tremendously successful,” Ortiz said.

Big compost plans

Compostable materials, particularly food scraps, remain a large target for the county. More than 31 percent of landfilled materials are compostable, the county has found. Ortiz said the department wants to exponentially increase food scraps recovery. The county’s compost facility doubled in size last year, and the department plans to increase it again in the coming year, he said.

Compostable materials, particularly food scraps, remain a large target for the county. More than 31 percent of landfilled materials are compostable, the county has found. Ortiz said the department wants to exponentially increase food scraps recovery. The county’s compost facility doubled in size last year, and the department plans to increase it again in the coming year, he said.

To supply the feedstock for the growing facility, the county is also increasing collection. It launched a curbside food scraps pilot program in November with grant funds from the U.S. EPA. That program will run for a year, with a goal of eventually rolling out curbside food scraps collection countywide and having it collected the same day as yard debris.

Commercial and multi-family recycling is another focus area for the county. Single-family recycling remains voluntary among residents, but business and multi-family properties are required to offer recycling service. For apartments, that requirement dates back to the early 1990s. During the upcoming 10-year plan, the county aims to increase enforcement and education for commercial and multi-family recycling, as these segments represent a large portion of the overall waste stream. Commercial entities, for example, contribute more than two-thirds of the material in the recyclables stream.

The county is also serious about its own internal materials diversion efforts. It launched a single-stream County Office Recycling Program in 2011, collecting material from its 80-plus office buildings. In 2015, that led to more than 265 tons of diverted office materials. To demonstrate the county’s commitment to waste diversion, department personnel are required to recycle materials in accordance with an official policy.

And if they don’t?

“If somebody puts a piece of paper in the trash bin, they could be written up for it just like if they were late to work,” Ortiz said.

This article originally appeared in the January 2018 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.