In the City of Madison, Wis., staying consistently ahead of the curve has led to high diversion and citizen engagement in municipal recycling.

In the City of Madison, Wis., staying consistently ahead of the curve has led to high diversion and citizen engagement in municipal recycling.

Curbside collection in Wisconsin’s capital dates back to 1968, two decades before many municipalities were beginning to establish collection programs. Its early implementation means the city’s recycling program is frequently dubbed the first curbside program in the nation.

In the early days, the program collected only newspaper, but in the late 1980s it began to evolve. Yard waste was banned from landfill disposal in Madison and the surrounding Dane County in 1989, and in 1991 the now-standard list of single-stream materials followed with a separate landfill ban. That countywide ban came ahead of a state landfill ban, and “the county law became kind of the model for the state law,” said George Dreckmann, former recycling coordinator for the City of Madison.

The city’s current recycling coordinator, Bryan Johnson, points to those initiatives as key components of the city’s positive diversion results.

“With the combination of city ordinances, county ordinances and everything working together, it’s kind of allowed us to be where we are today,” Johnson said.

Making it mandatory

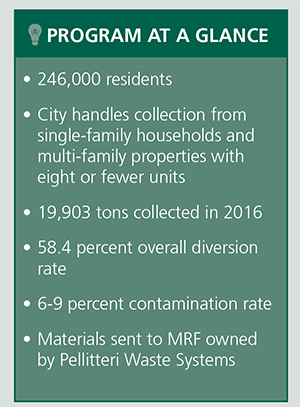

Madison makes it easy for residents to begin recycling. The program is budgeted out of property taxes rather than a utility fee, and residents do not have to “opt in” to receive recycling service. If a person lives in a single-family home in Madison, they receive recycling service. And residents are legally required to divert recyclables.

But these strategies haven’t required strong enforcement in Madison over the years. The city does not engage in active policing of the requirements and instead deals with problems on a case-by-case basis.

“If someone’s not putting out a recycling cart, we just tell them, ‘You start putting it out in two weeks or we’re going to stop collecting your trash,’” Dreckmann said. “That works really well. We haven’t issued fines, because people have complied.”

Statistics from the municipality suggest residents also get the message when it comes to putting the right materials in the cart. In 2016, Madison’s recycling stream had less than 10 percent contamination. That’s in part due to a series of “aggressive” public education initiatives, funded by sizable budgets, Dreckmann said.

When the program was going through big changes, public outreach efforts were allotted between $160,000 and $200,000 annually – although the education budget is currently much more modest at about $24,000 per year. A city ordinance requires landlords to share recycling information with their tenants both when they sign the lease and then every six months after that.

Madison’s Streets and Recycling division department regularly publishes a booklet called “Recyclopedia,” which educates residents on what and how to recycle. The city released a smartphone app called MyWaste, and the recycling program also maintains an internet presence via Recyclopedia as well as the city’s website.

Madison’s Streets and Recycling division department regularly publishes a booklet called “Recyclopedia,” which educates residents on what and how to recycle. The city released a smartphone app called MyWaste, and the recycling program also maintains an internet presence via Recyclopedia as well as the city’s website.

“People go to a website when they’re looking for an answer to a question, that’s a good thing,” Dreckmann said. “The weakness, though, is that they don’t sit around at home and go, ‘You know what, I’m bored, let me go to the streets division website and see what’s new in recycling.’ It’s not as effective a way to get out new information, as a television ad, a radio ad or a mailing or something like that.”

In fact, Madison’s long history of recycling means its program leaders have sage advice on a number of initiatives other municipalities might consider. For instance, the city began offering three recycling cart options to residents, something Dreckmann advised other programs to avoid – the city has to keep three different segments of cart components in a stockpile to repair broken carts, which has turned into a hassle.

However, Dreckmann does recommend mandatory recycling ordinances, especially in cities that do not utilize a pay-as-you-throw system. Although “mandatory” is often considered to have negative connotations, Dreckmann said public perception often comes down to how an initiative is enforced. And with the right type of sustained outreach, ensuring compliance becomes less of a concern.

Driving up diversion

So how have those initiatives played out for the city? The numbers tell a successful story.

The year the yard waste landfill ban and mandatory compost source-separation policy was implemented, the city’s diversion rate jumped from 18 percent to 34 percent. By 1996, seven years later, the city had achieved 50 percent diversion. Of that, roughly two-thirds was compost and the rest recyclables.

In 2016, the city collected 19,903 tons of recyclables. Its total diversion rate – a a statistic that also includes bulky items, electronics, yard waste and organics – was 58.4 percent.

The city’s Streets and Recycling division collects every other week from the 75,000 properties that are either single-family residences or are multi-family with eight or fewer units, and other multi-family and commercial properties use private collection.

Collected materials are sent to a nearby materials recovery facility operated by Pellitteri Waste Systems, and the partnership has led to some unique opportunities.

“We are able to include some things that are maybe not standard for a lot of curbside programs,” Johnson said. He pointed to plastic bags, which are allowed in recycling carts if they are bundled together. “We got to there because we were able to work with this private MRF to make it happen, because they’re a local, family-owned company that’s been waste-hauling in Madison for decades.”

This article originally appeared in the July issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.