This article originally appeared in the August 2017 issue of Plastics Recycling Update. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Together, they provide museum tours, child health and education centers and adult financial literacy classes. Thousands of impoverished people rely on them for survival. But they’re not charities or social welfare programs – these Latin American programs are run by local plastics reclaimers.

“Today, I say that recycling is a clear solution out of poverty for our Central American countries and Latin America,” said George Gatlin, general director of Honduras-based reclaimer Invema. “It offers a job to people of any age, any level of education, be it a man, be it a woman. They can go and have a better life because of recycling, and, as well, we provide a social solution to the problems that we have in Honduras.”

Gatlin was one of three speakers participating in a session focused on Latin America at the Plastics Recycling 2017 conference, which was held in early March in New Orleans. Joining him were Jaime Camara, founder and CEO of Mexico-based PetStar, and Jacobo Escriva, manager of the recycling division of Peru’s San Miguel Industrias (SMI), a packaging producer.

PetStar, SMI and Invema are trailblazers in their respective markets, a leadership position that presents both challenges and opportunities. Their growth mirrors the advancement of plastics recycling overall in Latin America, a region with nearly twice the population of the United States.

“All Latin American countries are really growing collection drastically,” said Camara, who sits on the board of the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR). “And, of course, the whole plastics recycling industry, specifically PET, is truly advanced and evolving.”

A global leader in Mexico

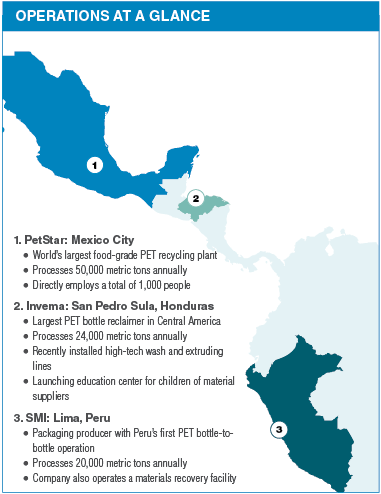

As CEO of PetStar, Camara heads what is described as the world’s largest food-grade PET recycling plant. The facility is located just outside of Mexico City, Latin America’s largest city. PetStar is owned by seven corporate shareholders, including Arca Continental, which is the third largest Coca-Cola bottler in the world; Coca-Cola de Mexico; and five other Coke bottlers.

The PetStar operation has exceeded its stated production limit by 25 percent.

The PetStar facility utilizes wash lines from Italy-based Amut and extrusion and solid-state polycondensation (SSP) equipment from Switzerland-headquartered Buhler Group.

A fully integrated reclaimer with a nominal capacity of 40,000 metric tons per year of post-consumer food-grade PET, PetStar is capable of exceeding its stated production limit by 25 percent, Camara said. It can produce 50,000 metric tons only because it controls the supply to the plant.

That was a point Camara emphasized: the importance of a robust collection system. His company runs eight collection plants around Mexico with 700 direct employees and 150 trucks.

Overall, his company employs 1,000 people. That number doesn’t include the estimated 24,000 scavengers, or waste pickers, who also rely on PetStar for their livelihoods. They supply PET bottles to PetStar collection trucks, which haul the material to company facilities for sorting and baling.

“We offer [pickers] certainty,” Camara said. “We offer them what we call the PetStar inclusive collection model: fair income without intermediaries.”

To achieve that certainty, PetStar has embarked on social-development efforts for its picker families, the kind of programs often undertaken by nonprofit organizations or governments. For example, in a poor quarter of Mexico City, it offers educational, food and health services to 250 children of pickers, an effort the company is about to replicate in three other Mexican cities, Camara said. The aim is to reduce children’s role in picking by giving them a formal education.

The company also supports social-impact projects in indigenous communities. On-site, it has a museum and auditorium it uses to educate school children about recycling. The museum-auditorium drew 12,800 visitors in 2016.

Camara also emphasized the environmentally friendly aspects of PetStar’s building and operations, part of what he called the “PetStar sustainable business model.” He pointed to efforts to reduce PetStar’s carbon footprint and water usage, prevent the leaking of plastics to the natural environment and decrease waste. He placed PetStar’s ambitions under the broader umbrella of the United Nations 2030 sustainable development goals while also emphasizing the importance of the New Plastics Economy initiative led by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

“The PetStar approach is really to become a benchmark for these global challenges, to this New Plastics Economy, and to demonstrate that recycling can be done in a profitable way with huge environmental impacts and huge social impacts,” Camara said.

Yet he also stressed the necessity of delivering a profit. PetStar’s post-consumer resin must be equal to or less than the price of virgin resin, he said. The company also works to add value to its byproducts, including green PET, exotic-color PET and other materials.

Together, PetStar’s owners have about a $100 million investment in the company’s infrastructure. PetStar is hoping to deliver earnings of 15.6 percent in 2017.

PetStar soration workers help maintain plant efficiency.

“In order to be truly sustainable, you have to be profitable,” he told the audience at Plastics Recycling 2017. “Otherwise, you will not endure and you will not survive.”

Peru’s first bottle-to-bottle facility

PetStar provided a model for SMI when the Peruvian company launched its recycling division four years ago, said Escriva. The first step his company took was to visit Camara to learn about PetStar’s business model.

SMI, a packaging producer with operations in seven Latin American companies, runs Peru’s first PET bottle-to-bottle recycling facility. It’s a new industry in the South American country of more than 30 million people – Peru in December 2014 became the last country in the region to allow the use of recycled PET resin in new beverage containers. SMI pushed the government to pass the law, Escriva said.

But the use of recycled PET in drink bottles is already advanced in Latin America, he noted.

“You can say that recycling bottle-to-bottle is already a trend in Latin America,” he told the audience. “You have brands like Coca-Cola, Villavicencio in Argentina, Postobon in Colombia and RainForest in Costa Rica that are already using good amounts of recycled resin in all their PET containers,” Escriva said.

SMI supplies recycled PET resin to Backus, a bottler that incorporates 25 percent recycled content in all beverage containers sold in Peru, he said.

SMI is able to collect and process 20,000 metric tons of discarded PET bottles per year, in part because it owns its own materials recovery facility (MRF). Its bottle processing facility is in Lima (SMI also opened a bottle recycling facility in Bogota, Colombia in late 2015). The Lima processing facility uses Technofer washing systems and Starlinger extrusion equipment.

PetStar uses 150 trucks to connect its eight collection sites with the central processing facility.

Escriva emphasized the environmental, economic and social benefits of bottle-to-bottle recycling in Peru. In a country where over 90 percent of waste ends up in an estimated 1,850 informal landfills, SMI helps make a dent in the volumes landfilled or burned. SMI also helps offset the need for PET imports, improving Peru’s trade balance to the tune of $40 million per year, according to Escriva. It also provides income for thousands of pickers who provide PET bottles to a network of 29 SMI suppliers in Peru.

“It’s still pretty informal and not very efficient, so this is where we’re putting all our efforts,” Escriva said.

Escriva was clear about the challenges the company faces in Peru. One of those is the export of PET containers to neighboring Ecuador, where smugglers can illegally redeem them for 2 cents each. Ecuador’s subsidies drive the export of approximately 18,000 metric tons of PET from Peru to Ecuador annually, he said. In the past, it only made it difficult for SMI to acquire material in northern Peru, adjacent to Ecuador, but, more recently, suppliers from as far away as Lima have also begun sending bottles across the border, he said.

Other challenges include a poorly developed market with a high concentration of suppliers and a lack of technology, he said. Then there’s geography.

Currently, most of SMI’s suppliers are concentrated in the Lima region, where about one-third of the country’s population resides. Expanding collections to the jungle regions to the north and south is difficult because of long distances, the physical barrier of the Andes Mountains and lower volumes of material, all of which challenge the freight economics. SMI also faces competition from PET exports, which destabilize the market, require lower quality material and enjoy a freight advantage.

Lastly, in Peru, SMI competes against the cheapest virgin PET in Latin America. That’s because the country lacks tariffs on PET imports and freight costs are lower than those in many other countries. For example, Colombia slaps a 10 percent tariff on imports of virgin PET, and the distance from the country’s Buenaventura port to the capital of Bogota is 314 miles. In comparison, Peru has no tariffs, and the distance from its Callao port to Lima is four miles.

SMI is pushing the country’s government to change its regulatory framework to boost recycling, Escriva said. For example, it is calling for legislation making packaging producers responsible for the end-of-life management of their products. It also wants the government to reduce entry barriers for recyclers and formalize collectors in a national registry. Lastly, it would like to see the Ministry of Environment set recovery targets, fund municipal projects and take other steps to boost recycling, he said.

“The target is to generate a profitable and sustainable recycling industry according to the needs and reality of Peru,” Escriva said.

Advancing through upgraded equipment

Meanwhile, in Honduras, Invema is a company just starting to produce food-grade recycled plastics.

Invema is located in the city of San Pedro Sula, not far from the Caribbean Sea in the north of Honduras, a country of just over 8 million people. Founded by Gatlin in 1994 as an aluminum can recycling company, Invema today is the largest PET bottle reclaimer in Central America, processing about 24,000 metric tons per year.

It is poised for further growth with the recent installations of new equipment to wash and extrude plastics into food-grade pellets and sheets. A Herbold wash line that can run 3 tons per hour was installed in July 2016, a Starlinger pellet line was installed this January and a Starlinger sheet line was installed in March. Even going from high-speed friction washers with no boilers or chemical usage to a wash line using chemicals and boilers, Invema is still enjoying a 20 percent energy savings in addition to higher-quality product, Gatlin said.

The company chose the equipment providers after consulting with Plastics Forming Enterprises (PFE), a New Hampshire-based independent testing and research-and-development company, he said.

Using the equipment, Invema plans to produce 630 tons of food-grade pellets and 500 tons of food-grade sheet per month, in addition to selling about 870 tons of flake on the open market.

“This way, one of the most important things we’ll be able to do is diversify and not be limited to one thing,” Gatlin told the audience. “By being diversified, we can add value to what we’re doing and, more importantly, create stability to our suppliers.”

The equipment came as a condition of Invema installing solar panels, Gatlin explained. The Washington, D.C.-based Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) provided assistance to purchase the wash line and extrusion equipment but only if Invema agreed to install solar panels as part of a study to determine their effectiveness in reducing energy users’ costs. So in September 2015 Invema installed 3,640 solar panels capable of generating 1 megawatt of electricity. After experiencing a 30 percent reduction in energy costs over the the first year, the company is now set to double its solar-generation capacity. The expansion will make it the second-largest producer of solar power for private consumption in Honduras.

The equipment came as a condition of Invema installing solar panels, Gatlin explained. The Washington, D.C.-based Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) provided assistance to purchase the wash line and extrusion equipment but only if Invema agreed to install solar panels as part of a study to determine their effectiveness in reducing energy users’ costs. So in September 2015 Invema installed 3,640 solar panels capable of generating 1 megawatt of electricity. After experiencing a 30 percent reduction in energy costs over the the first year, the company is now set to double its solar-generation capacity. The expansion will make it the second-largest producer of solar power for private consumption in Honduras.

Invema has also worked to recycle caps, rings and labels, items that were long simply a waste byproduct of the washing line, Gatlin said. For those items, the company installed a Herbold polyolefin wash line and an NGR extruder, and today it is producing PP and HDPE pellets from those materials.

“It hasn’t been easy. It’s a very complicated thing to do, and we’re still refining it,” he said. “But at least we’re able to use the whole bottle, and that’s great.”

Invema directly employs 385 people, but, similar to PetStar and SMI’s recycling division, it relies on informal pickers to generate its feedstock. In fact, Gatlin gave the informal sector credit for helping the company grow. And that growth has involved supporting those individuals in turn. Invema prohibits children from entering its facility, so some pickers leave their kids outside while they sell scrap inside.

“It’s just so sad to see a 5-year-old boy or girl sitting on the sidewalk there,” Gatlin said. “So … we’re starting a children’s education center where the parents can come in and leave the kids at the education center while they go and sell scrap. The kids can play, can learn why to recycle, how to recycle and what happens if they don’t recycle. And, hopefully, some day they’ll become suppliers as well.”

Invema has seen suppliers lifted out of poverty by selling their scrap. Some, however, spend their new-found money on drugs, alcohol or gambling. So Invema started offering them financial responsibility classes every two months.

“Suppliers who know how to handle their money will be long-term suppliers and happy suppliers,” he said. “If they grow and they’re stable, then we grow as well.”

Jared Paben is the associate editor of Plastics Recycling Update and can be contacted at [email protected].

For more analysis on plastics recovery in emerging economies, attend Plastics Recycling 2018, to be held Feb. 19-21, 2018 in Nashville, Tenn.