The technology for sorting and recycling PP back into food-grade packaging already exists, and with more value chain alignment, it is poised to take off at scale, those involved at all levels of the process said during a session at the 2025 Plastics Recycling Conference.

Held outside of Washington, D.C., in late March, the session was a full value chain perspective on making PP food-grade. The speakers came from all points of the material flow: Neil Darin, senior director of resiliency and holistic packaging at TMS, which helps brands source materials; Robert Flores, senior vice president of sustainability at Berry Global; Edward Kosior, president of NextLooPP Americas; and Jeff Snyder, senior vice president of recycling at Rumpke. It was moderated by Dan Liswood, senior director of the NextGen Consortium at Closed Loop Partners.

Interest in recycling PP has steadily grown over the past few years, Snyder said: “If you’d asked me to do this five years ago, I wouldn’t know what the heck I was talking about.

“It just goes to show that polypropylene has really came on board here in the collection and the sorting side,” he added, and PP is everywhere now.

MRF upgrade enables PP recovery

A recent report from Closed Loop Partners found that in a study of 650 tons of material that came through four MRFs with Greyparrot AI systems, between 75% and 85% of the PP was white or clear, most of which was presumed to be food-grade. Beverage cups made up over 30% of the clear PP, lids were 27% and tubs were 20%, with the remaining fraction made up of trays, lids with straw holes and undefined items.

Rumpke started working on taking PP tubs and cups five years ago, receiving a grant from The Recycling Partnership in 2020 to upgrade MRF infrastructure and equipment such as optical sorters and AI. Now, Rumpke’s facility in Cincinnati sells about 60 tons of PP per week.

“A lot of the problems when you add new commodities into a material recovery facility is to have the space and the infrastructure,” Snyder said. “To be able to make those changes to add a commodity, you need a place to store it, you have to have a way to sort it and those things go on and on. It takes time for a lot of our industry to kind of catch up to that.”

Brands can help support that adoption, he added, and in the case of PP have done so in many cases.

Berry Global is one of the largest converters of PP packaging worldwide and operates several polypropylene recycling plants in Europe, one of which has a FDA letter of non-objection. Flores said it also takes time to educate consumers, especially on the finer points such as PP tubs versus cups.

“There’s just a lot of polypropylene out there. Consumers have never been perfect at recycling,” he said, so giving them more options helps.

Vast untapped potential for feedstock

Kosior, who is based in the U.K., pointed out that today, PP is as popular a packaging material as PET, “yet it’s only recycled at a fraction of that rate.”

About 8% of the 1.2 million tons of post-consumer PP that goes onto the market annually gets recycled, he said, “so there’s a great opportunity to put that material back into the circular pathway.”

Even so, that rate is a vast improvement over the past, Kosior said. About 15 years ago in the U.K., “very little polypropylene was being recycled – it was the material left at the end of the belt, and it was sent off to landfill or waste-to-energy.”

However, due to landfill fees, there was a local push to target PP for recovery. Only a few municipalities added it to their collection lists back then, but now 80% do.

“This has made a huge difference to the collection of material, and it gave the recyclers a chance to do something with this unique and very versatile material,” he said.

There was some up-front work done with MRFs to develop end markets, Kosior said, and while getting recycled PP into non-food-grade products is relatively easy, “the issue of food grade is another story altogether.”

Improvement in sorting is helping address that, along with better decontamination technology.

“Sorting is where it all starts right now,” Kosior said. “We can separate food from non-food polypropylene. We’re about to do a major experiment where we’re going to sort on melt index. In a month’s time I’ll tell you the results of that work.”

Design tweaks can enable sorting success

Part of better sorting and decontamination is doing the work upstream, at the design stage, to make processing easier, the panelists agreed.

Kosior said additives should be chosen carefully to ensure that the PP, which from a chemical standpoint is less stable than PET or HDPE, actually can be recycled. Design also needs to take into account the way AI learns and how it has already been trained.

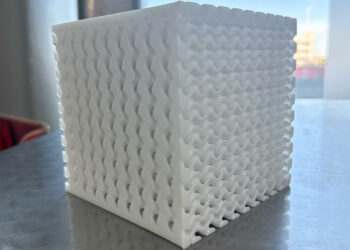

“When we’ve been training AI systems to identify polypropylene food packaging, for example, in trays, we’ll get a fragment of the tray and the tray will have dimples and ribs in it. So the machine has taught itself that food trays have got dimples and ribs,” he said. “What that means is when we start to design for the circular economy, we have to use stereotypical attributes into the products.”

New designs should stay within broad design rules, or AI will have to be re-trained to recognize specific designs, which is not efficient, Kosior said.

“We’re going to enter this new phase of being much more careful about material selection, material stabilization and design packaging,” he predicted.

Dyes and labels also need scrutiny and changes, Darin added, with in-mold labels being the most challenging aspect.

“Not everything is appropriate for recycling and recovery in a design respect, so we just need to make sure that other brands are adopting the right technologies, using the right tools, making the right assessments and designing it appropriately, no matter how they choose to decorate,” Darin said.

Kosior said NextLooPP Americas has developed removable in-mold labels that will debond during the recycling process. That’s a project that demonstrates the importance of everyone working together.

“Converters give the recyclers all this stuff and they say, ‘here, fix it,'” he said. “We actually need the converters to not wreck it at the beginning and get it right, so it makes the recyclers’ life better, cheaper, easier and more productive, giving a high quality resin back. They’re all part of the same whole cycle. I think if everyone understood we’re all on the same journey of making plastics more recyclable, it would make the whole process a lot easier and more productive and lower cost.”