Sebastian_Photography/Shutterstock.

This article appeared in the 2024 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

There’s one very simple, unavoidable reason that global industry is at least eventually going to have to rely more heavily on recycling in order to satisfy its seemingly ever-growing demand for precious metals for its products: Several of the major mining operations around the world are in advanced stages of their life cycles.

Already, for example, South Africa’s mines are being dug 2 and 3 kilometers deep. Precious metals are a finite resource, and — given today’s rising dependance on them in a range of products — we can envision shortages of gold, iridium, osmium, palladium, platinum, rhodium, ruthenium and/or silver coming in the decades ahead. New sources are being explored, but they come at a high price.

That is only one of the reasons, however. There are multiple other factors that portend change for the precious-metals landscape. They all point to more recycling and recovering of the precious metals that already are within industry’s grasp.

The Environmental Factors

There has been a study performed twice by the International Platinum Group Metals Association, a nonprofit association which represents leading mining, production and fabrication companies in the platinum, palladium, iridium, rhodium, osmium and ruthenium industries. Member companies have been surveyed on the carbon output of their recycling processes for platinum-group metals, which are produced from the same ore mined primarily in Russia, South Africa and North America. The result was so shocking in the first run that it prompted the IPA to undertake the study a second time with greater scrutiny. The findings grew even more dramatic the second time around: Recycling can reduce the carbon output of precious metals by more than 90% versus mining.

“Effective strategies for end-of-life management of equipment containing PGMs must be established to minimise collection losses and ensure every gram of PGMs can be reused,” the IPA later wrote. “There is also scope for improved collection of the metals from existing applications to boost the recycled supply of these metals. Policies improving the collection of end-of-life PGM-containing equipment are essential to help to maximise recycling.”

Even when we think of the relatively large energy input demanded by some of the recycling processes that are employed around the world, those processes still contribute only a minute fraction of the carbon footprint compared to the use of heavy machinery and equipment in mining precious metals.

Furthermore, recycling is such a more efficient method to attain the resource. It varies depending on the vein of the ore, but about 1 ton of mined gold ore typically can be expected to yield about 5 grams of gold. On the other hand, 1 ton of cell phones, about 10,000 devices, can yield up to 280 grams of gold.

The Geopolitical Factors

Geopolitical experiences and their impact on various business sectors in the last several years also suggest change is coming for precious metals. Shortages of nickel and neon were marked throughout global supply chains in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example. Pandemic-related interruptions also exposed the unsustainability of typical supply lines for many rare-earth metals. Industry seeks more flexibility in how they source metals, and the London Bullion Market Association and London Platinum & Palladium Market can help suppliers of precious metals connect with suppliers to achieve stable procurement.

Ethical questions around various geopolitical issues also have grown more pressing: Where are the precious metals coming from? How were the metals obtained? Today’s requests for proposals and quotations sometimes require manufacturers to rely on only “conflict-free” metals in their products. As described by the European Union in its explanation of regulations in this area, “In politically unstable areas, armed groups often use forced labor to mine minerals. They then sell those minerals to fund their activities, for example to buy weapons. These so-called ‘conflict minerals,’ such as tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold, can find their way into our mobile phones, cars and jewelry.”

Again, the LBMA and LPPM can assist suppliers of precious metals in undertaking responsible mineral sourcing programs that address ethical issues in areas such as human rights and environmental impact.

The Business-Model Factors

Of course, the gathering scarcity of precious metals to be mined from the earth will gradually improve the business models for different ways of sourcing precious metals. As mines run dry and, in turn, prices for mined precious metals rise, the economic arguments for instead refurbishing and repurposing products with precious metals in them or recovering metals from production scrap will grow more compelling.

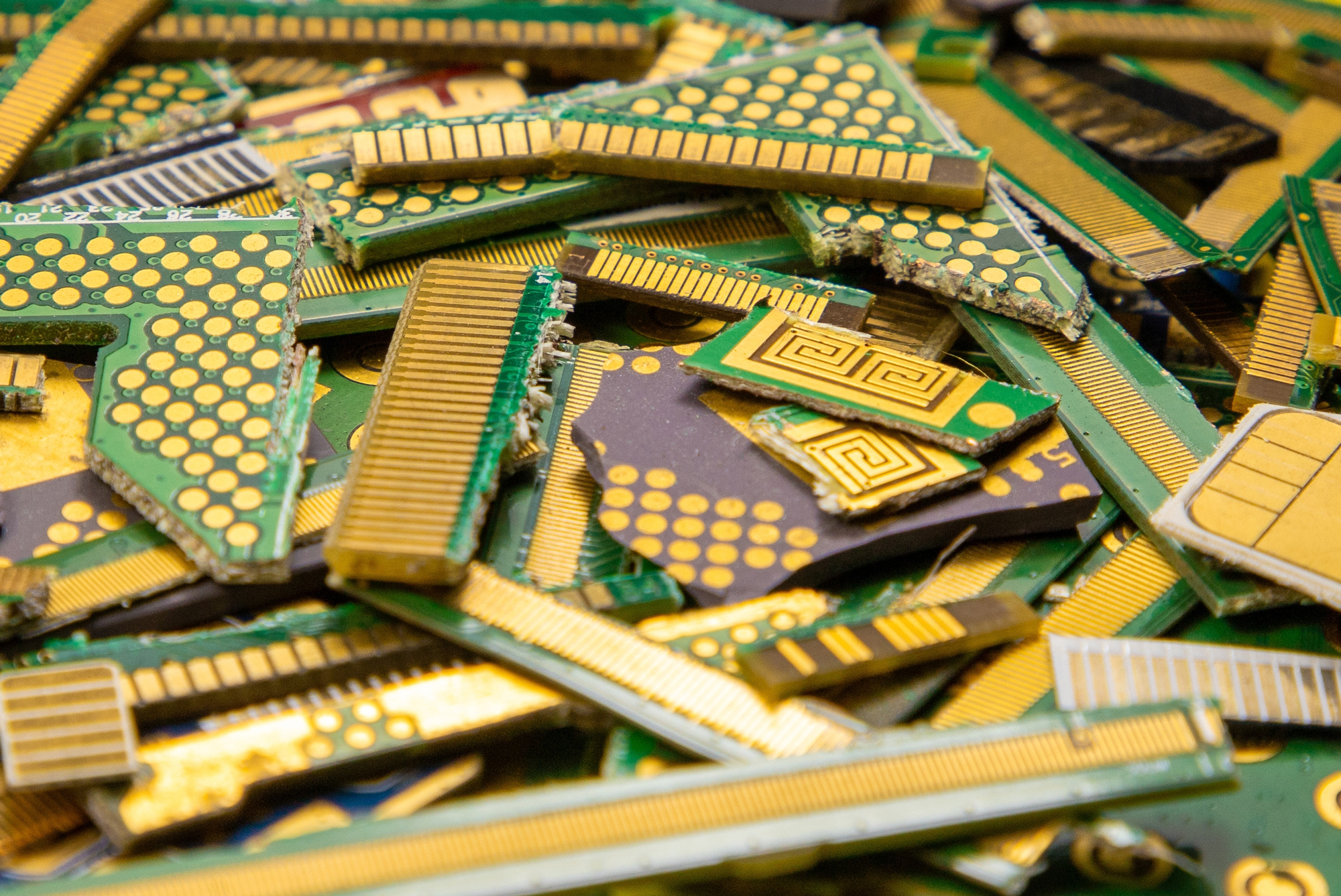

E-scrap contains valuable and finite resources that can be reused if properly recycled. Precious metal raw materials that are 100% recycled resources are difficult to achieve without further recovery. It is important to deepen the understanding of precious metal recovery from manufacturers to general consumers, in order to promote the precious metal recycling business.

Such market-driven realities might ultimately have the greatest influence on changing the ways that industries globally attain the precious metals that they require. Indeed, there already are a number of diverse factors other than the evaporating raw supply and evolving economic equation that are fanning greater interest in recycling these metals.

Bodo Albrecht is president of Tanaka Precious Metals (Americas), responsible for all operations in North, Central, and South America, including sales, distribution and support for all Tanaka products in close cooperation with manufacturing, marketing, technical, research and development and related operations in Asia. He is a precious metals executive with deep roots in the industry, as well as in rare earth elements and strategic metals, with 20 years of international management positions with Degussa AG and 15 years running a consulting firm, BASIQ Corporation, before joining Tanaka.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Resource Recycling, Inc. If you have a subject you wish to cover in an op-ed, please send a short proposal to [email protected] for consideration.