This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The global pandemic has rewritten the market playbook for the recycling industry in 2020.

While the “COVID-19 effect” has touched all recyclables, the aluminum and copper markets are prime examples of the significant market factors at play and the profound uncertainty and challenges recyclers face going forward.

Of auto production and aluminum demand

The aluminum and copper scrap markets weren’t in great shape before the pandemic. One reason was the eroding health of the U.S. manufacturing sector, a key driver of aluminum and copper demand. Since the fourth quarter of 2018, U.S. manufacturing output has been either declining or treading water, and it plummeted in the first quarter of 2020, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reports.

Other key indicators revealed worrisome signs in the U.S. economy overall. For example, the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index for the U.S. declined in four of the final five months of 2019. The much-watched index, which is a composite of economic indicators used to forecast the direction of the economy, did inch upward in January and February 2020, but it slid 7.4% in March, the largest monthly decline in the index’s 60-year history. When it slipped another 4.4% in April, it helped confirm that the U.S. economy was in recession.

The sobering U.S. economic conditions have reduced the demand for and prices of recycled commodities and tightened scrap supplies due to lower manufacturing (and scrap generation) levels as well as decreased over-the-scale peddler traffic. U.S. supplies of aluminum scrap, for example, slid almost 9% in 2019 to 3.38 million metric tons, based on U.S. Geological Survey data and estimates from the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI).

“Price provides the incentive for people to bring scrap materials to market,” said Joe Pickard, chief economist and director of commodities for ISRI. “There was a slump in the supply of scrap metals coming into the market in 2019, so conditions were already challenging.”

For aluminum, automobile manufacturing is critical to market health. This is due to the growing amount of aluminum in new vehicles. An average auto could contain 565 pounds of aluminum per vehicle – 16% of total vehicle weight – by 2028, according to an Aluminum Association-sponsored survey.

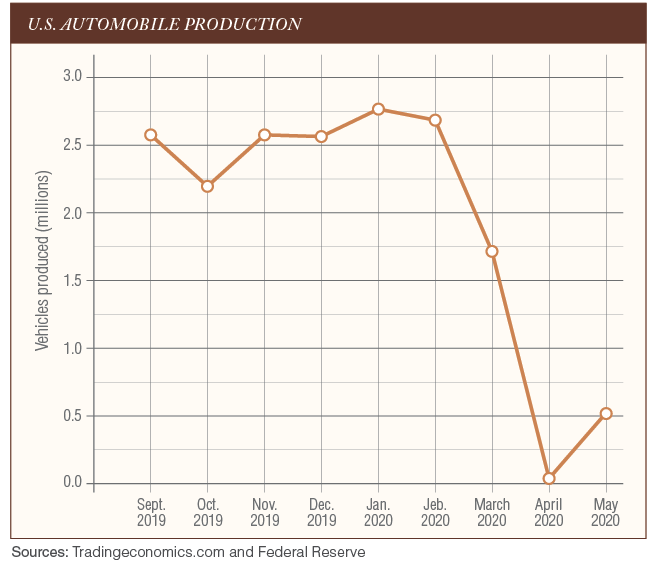

Unfortunately for the light metal, U.S. auto production was declining even before the pandemic, and it fell off a cliff for several months in 2020. In March, for instance, U.S. auto production dropped 35% from February levels to about 1.7 million units. Then, in April, production plummeted 99% to only 103,000 units before clawing its way back up to 542,700 units in May.

“U.S. vehicle production almost came to a complete stop for the better part of two months,” Pickard said. “When that happens, it has extremely large impacts on the recycling industry in terms of the supply and demand for scrap.” And forecasts for total 2020 U.S. auto production aren’t giving recyclers much cause to smile, with LMC Automotive predicting in June that U.S. auto output could end the year down almost 21% compared with 2019.

Challenging UBC market trends

The fundamentals for aluminum used beverage cans (UBCs) provide another example of the market factors influencing aluminum scrap. One big-picture trend has been the steady reduction in U.S. production of aluminum can sheet in favor of aluminum auto-body sheet, which is a higher-value product for producers and a growing market (except in recent history).

This shift has become so pronounced that there’s now a shortage of domestically produced aluminum can sheet, said Matt Kripke, president of Kripke Enterprises, a non-ferrous scrap brokerage company.

U.S. trade politics also have played a part in discouraging domestic production of aluminum can sheet. In 2018, the U.S. imposed Section 232 tariffs on various imported aluminum products, including aluminum can sheet. U.S. users of that sheet, however, requested and received an exemption to import it without the tariff.

The drop in U.S. auto production and higher imports of aluminum can sheet have depressed the demand, prices and supply of various grades of aluminum scrap, including UBCs.

Export demand for U.S. aluminum scrap provided some positive news for recyclers in 2019, rising almost 6% to 1.86 million metric tons, despite a 36% decline in China’s demand. The story is different this year. From January through April, U.S. aluminum scrap exports were down 6.5% compared with the first four months of 2019, to approximately 582,000 metric tons, with India serving as the largest buyer and China continuing to cut its purchases (down another 58%).

Copper’s export problems

As with aluminum scrap, domestic U.S. demand for copper scrap has been far from great the past couple of years. “There aren’t many domestic consumers of copper scrap, and that sector has been consolidating over the past couple of decades, which has made for challenging domestic market conditions,” ISRI’s Pickard said.

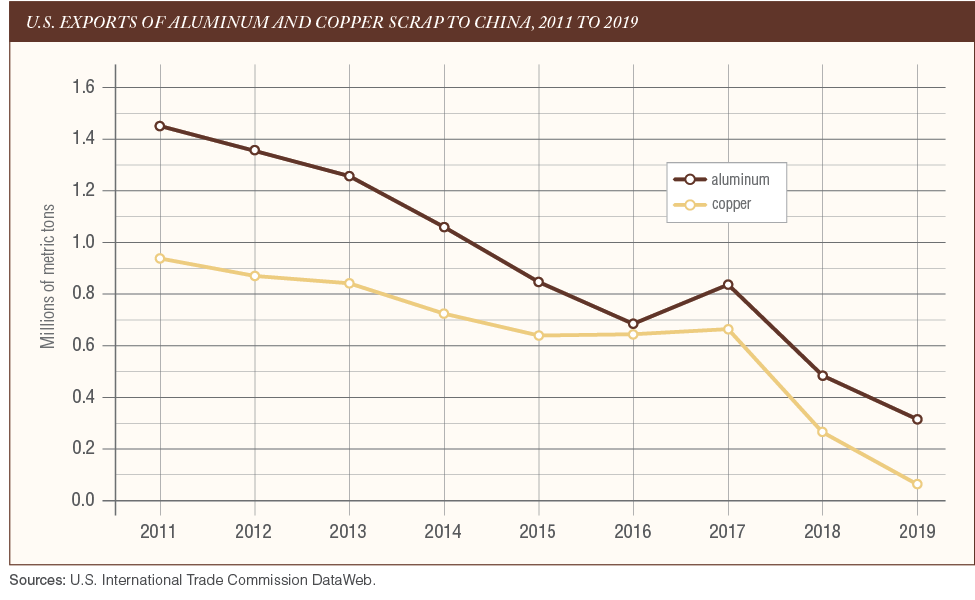

Given the limited domestic demand for copper scrap, U.S. recyclers have relied heavily on the export market – and China in particular. Beginning in 2000, China became the key export outlet for U.S. copper scrap, reaching its buying peak of roughly 944,000 metric tons in 2011. Then China’s import behavior started to change. It began implementing tighter inspection and quality standards on imported recyclables to prevent low-quality material from entering its borders. It imposed import bans on certain commodities (such as plastics and mixed paper). It set quotas restricting the amount of some recyclables allowed into the country each year. And when its trade war with the U.S. kicked in beginning in 2018, China imposed tariffs on scrap imports, including aluminum and copper scrap.

“All of a sudden there was an oversupply of the copper scrap grades that weren’t leaving our shores,” said Rob Wise, account executive for Ferrous Processing & Trading Co., a ferrous and non-ferrous scrap recycling company. “That meant domestic consumers could be a lot more picky about what they bought and what they didn’t buy.” It also meant U.S. exporters had to find other markets for their copper scrap. “We all started selling material to other countries for upgrading before it goes on to mainland China,” Wise said.

China’s import restrictions and trade tensions with the U.S. have had a dramatic effect on U.S. copper scrap exports, with shipments to mainland China plummeting 68% in one year, from about 271,000 metric tons in 2018 to 88,000 metric tons in 2019. The U.S. copper scrap export picture in 2020 (January through April) continued the downward trend, with overall shipments declining 21% to 242,000 metric tons and exports to China down 40% to roughly 23,000 metric tons.

On the domestic market front, the pandemic has tightened copper scrap supplies in 2020. “Supply was basically nonexistent starting in March,” Wise noted. Domestic demand, meanwhile, has been surprisingly stable. “There’s no shortage of calls from buyers looking for copper scrap,” he said. “It has started to be a race between scrap companies to see who can pay the tightest spread to get the metal units into their door.”

While the domestic copper scrap picture has brightened in the short term, global primary copper fundamentals could cloud the picture for recyclers. According to the Portugal-based International Copper Study Group, the world’s refined copper production likely will exceed demand by more than 280,000 metric tons in 2020, reversing several years of supply deficits. “A return to refined copper surpluses would only complicate the outlook for copper recyclers on the supply side,” Pickard said.

A Chinese wild card?

Going forward, one development could bode well for aluminum and copper scrap export demand. China announced plans early in 2020 to introduce new import standards for high-quality aluminum, brass and copper scrap, essentially reclassifying the metals from “waste and scrap” to “recycled raw materials.” According to Adina Renee Adler, ISRI’s vice president of advocacy, “these standards are China’s acknowledgement that scrap is not waste, that these recycled metals are actually products.”

China’s new standards would divide brass scrap into four basic categories that would encompass eight specific grades of brass scrap. Similarly, copper scrap would have five general categories covering 11 specific grades. Aluminum would have three basic categories – aluminum casting, recycled aluminum ingot and aluminum block – with the last category divided into three specific grades based on the size of the aluminum block.

Each of the new grades has its own purity levels on total metal content (which takes into account metals other than the specified metal) and content of the specified metal alone. The new grades cannot contain any “forbidden carried wastes,” including household waste, medical waste and items that are radioactive or explosive. Some grades also have moisture limits, and there are specific packaging, labeling and documentation requirements. “What China is trying to do through these new standards is create a regime where it can import higher-quality metals from recycling processes that are melt-ready,” Adler said.

Why is China proposing these changes now? One reason, Adler said, is “China recognizes that its manufacturers need the metal. Its domestic scrap collection can’t meet all the production demands of its manufacturing industry.” Another reason is that using scrap is more environmentally beneficial than producing metal from virgin resources, which aligns with China’s goal of reducing pollution, Pickard said. In addition, scrap is less expensive than primary metal, which improves the competitiveness of Chinese manufacturers.

China initially planned to implement the new standards on July 1, but it missed that self-imposed deadline. Some market watchers say China might not finalize the new specs until 2021. Until China implements the final standards, several issues remain up in the air.

For instance, if high-grade aluminum, brass and copper metals are considered “recycled raw materials” rather than “waste and scrap,” Chinese buyers could import them as products or merchandise, free from China’s scrap import limitations. Also, it’s unclear whether metals shipped under the new standards must meet the current pre-shipment inspection requirements that apply to scrap cargo. “Everyone is just in a holding pattern to see what comes out of it and what becomes official,” said Tony Levin, vice president of Ferrous Processing & Trading Co. “China’s always a wild card. You never know what’s going to happen there, and there usually isn’t a lot of advance notice.”

One other question is whether recyclers can meet China’s new specs.

“They are achievable,” Adler said. “There are recyclers who already can meet the new specs, but they were willing to make the investment in the processing equipment needed to meet the requirements.” Meeting China’s new specs won’t come without additional processing costs, however. “I’d need to get 5 cents a pound or more above the current market price to go through the steps required – and frankly I don’t know if China’s going to pay that premium for the material,” Levin said.

In the bigger picture, the ongoing downturn in China’s economy at large also could limit the positive effects of its new import standards. China’s economic growth declined from 6.8% in 2017 to 6.6% in 2018 and further to 6.15% in 2019. In the first quarter of 2020, China’s economy contracted 6.8%, with predictions saying its annual economic growth could be less than 2%.

Hoping to break even

Given that market scenario, what can aluminum and copper recyclers expect going forward? It largely depends on the course of the pandemic because that will determine if there’s enough economic recovery to affect the supply, demand and prices of recyclable commodities.

In Levin’s view, “as long as the auto industry keeps producing cars, U.S. aluminum will continue to improve in terms of market demand and prices.” Also, as manufacturers, bottle-bill states and scrap recyclers resume their normal operations, the supply of UBCs and other aluminum and copper scrap grades will grow, though the market won’t change overnight. For copper scrap, “I don’t see any immediate turnaround in the supply issue,” Wise said. “Supply will be tight for a while, and we’re kind of in a wait-and-see until then.”

Speaking as one recycler in the trenches, Kripke said his company’s objective is to reach break-even by the end of the year. “We’re going to lose money in the first half, so we’ll try to find a way to rally in the second half.” He thinks many recycling companies are in that same boat, and he hopes they did what Kripke did, which was to leave money in the company to survive tough market periods like today. “This certainly is a rainy day,” he said.

Kent Kiser, former publisher of Scrap magazine and assistant vice president of industry communications for ISRI, is a freelance writer based in Arlington, Va. He can be contacted at [email protected].