SEELAMPUR DISTRICT, NEW DELHI —

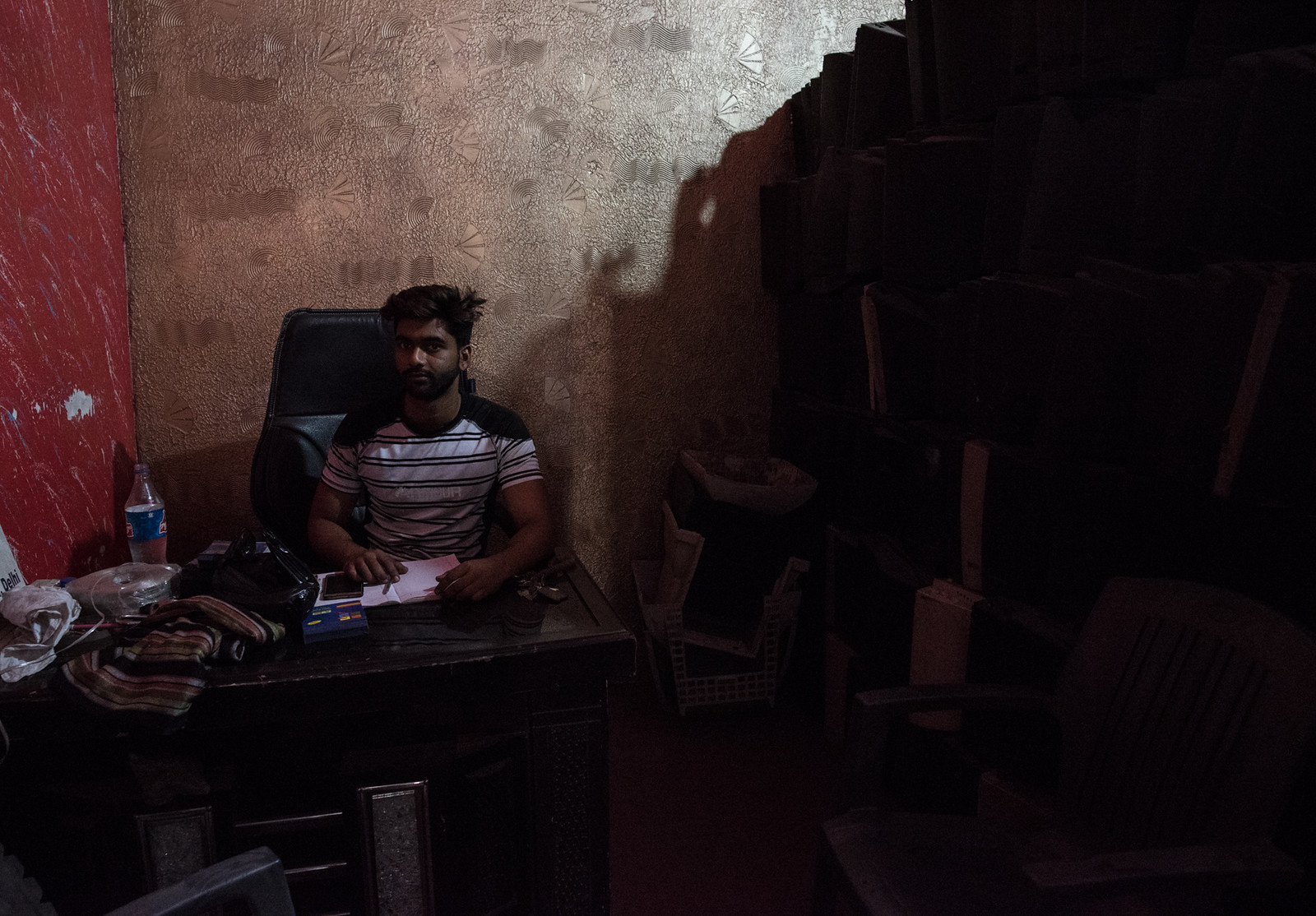

Off a narrow, sun-bleached alley, where the early summer heat stuns by mid-morning, Sakib Malik sits behind a desk in near darkness. Beside him, stacks of plastic casings from old CRT televisions arch toward the ceiling. He’s on the phone, amid another deal.

A handsome man in his mid-20s, Malik has run e-plastics aggregator Adash Traders for five years. He says he only handles CRT plastics and gathers material from “lots of places, from ragpickers to offices,” before reselling them in bulk to recyclers. After paying wages and clearing other overhead expenses, he earns the equivalent of about $5 for each metric ton of material. To make more money, Malik wants to hoist himself to the next lucrative rung in the e-scrap value chain by learning how to melt and recycle the plastics himself.

Malik’s operation exemplifies the complexities of e-scrap management in India today. Adash Traders is methodically run and leverages its expertise in a very specific area of electronics recovery to ensure profits and diversion of material from the waste stream. At the same time, the business is unregistered, or “informal,” and thus not approved by the government to collect, dismantle or recycle used electronics.

Over 90 percent of India’s e-scrap enters the informal sector for processing by people like Malik, according to a national assessment and follow-up studies by nonprofit groups and academic institutions. In fact, the Seelampur slum Malik calls home has become one of India’s most concentrated centers of electronics dismantling and recycling, with an estimated 25,000 informal workers. Similar processing clusters exist throughout India, the world’s second-most-populous country with a population of 1.32 billion.

Though the informal sector has proven its ability to gobble up huge tonnages of material generated within India and around the world, it also has a dark side. Because unregistered outlets dominate the process, oversight and due diligence are rarely part of the picture. In the case of Malik and Adash Traders, for instance, there’s also no systematic tracking of where material goes once it leaves his shop. As a result, lower-value material at times gets dumped or ends up in crude processing sites that put workers and the environment at risk.

Increased international media scrutiny of these realities has helped push Indian policymakers and other stakeholders to try to formalize the sector. In 2016, an extended producer responsibility system went into effect, mandating electronics producers to help manage a nationwide e-scrap system.

That has all led to a unique e-scrap dichotomy. On one side is a well-established, if problematic, informal structure that brings reliable incomes to huge numbers of workers. On the other is a nascent formal sector that must meet lofty health and safety aspirations but which finds itself struggling to compete with unregistered players who can offer better prices and leverage market connections that often run back generations.

Can the two arms find a way to work together? India is trying to find out. And with materials tonnages in India’s end-of-life stream projected to surge, the stakes and complications are only growing.