This article originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

For the U.S. to truly move the needle on recovery of food material, it’s clear local programs will need to do more than just target the residential sector.

Huge tonnages of food head into the waste stream from restaurants, food producers and many other players in the commercial realm. Many major generators have made admirable moves to divert more of this material. But one perhaps overlooked area is smaller, independent businesses that may not have the in-house expertise to launch initiatives.

The efforts under way in two solid waste districts in Vermont show how a variety of stakeholders can work together to find mutually beneficial solutions that keep food out of landfills. Generators in the Green Mountain State are in a relatively unique situation in that they are required by state law to take action on this issue, but the steps organizers and operators are taking there can help inform progress on organics in any jurisdiction.

Bringing businesses on board

With around 627,000 residents, Vermont is the second-least-populous state in the U.S. (only Wyoming has fewer people). But its commercial food-service sector is robust.

The state’s reputation for outdoor recreation and healthy living attracts people from around the U.S. and Canada to its ski areas, summer outdoor activities and autumn “leaf peeping” opportunities. The state is home to approximately 80,000 small businesses, including shops, restaurants, resorts, hotels and breweries.

In 2012, both to address Vermont’s stagnant recycling rate and to conserve space in its only operating landfill, the state legislature unanimously passed Act 148, the Universal Recycling and Composting Law. The law bans disposal of three major types of materials:

- Recyclables, including paper and cardboard; aluminum (cans, foil, pie tins); steel cans; glass bottles; and PET and HDPE plastic containers (bottles and jugs).

- Yard debris and clean wood

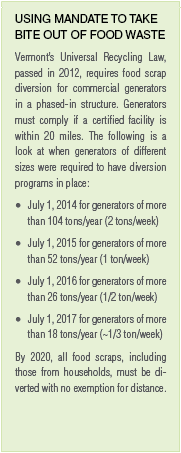

- Food scraps, phased in starting with the largest generators and becoming a full ban by July 2020 (see sidebar for complete details).

The Vermont Agency of Natural Resources has worked with solid waste districts, towns, haulers, processors, businesses and other stakeholders to roll out educational resources about source reduction, recovery, recycling and composting. To assist in implementation of the law, the state provides grants and other assistance to solid waste management entities (districts, alliances and towns).

The Vermont Agency of Natural Resources has worked with solid waste districts, towns, haulers, processors, businesses and other stakeholders to roll out educational resources about source reduction, recovery, recycling and composting. To assist in implementation of the law, the state provides grants and other assistance to solid waste management entities (districts, alliances and towns).

Last fall, several of these entities were awarded grants to conduct business outreach for recycling and organics diversion. The nonprofit Northeast Recycling Council was a partner in helping to provide technical assistance in two districts, the Lamoille Regional Solid Waste Management District (LRSWMD) and the Windham Solid Waste Management District (WSWMD).

LRSWMD, located in the rural northern part of the state, implemented a Sustainable Solutions Business Program. The district made direct contact with more than 100 businesses and provided comprehensive on-site trainings to 25 businesses (approximately 22 percent of the businesses in the district). Most trainings took place at locations in Stowe, a popular year-round tourist destination with a population of 4,300.

Meanwhile, utilizing its outreach grant, WSWMD contacted 80 businesses and institutions, primarily located in Brattleboro, which is situated in the southern part of the state on the Massachusetts border and has a population of 12,040. In this effort, food scrap generators received on-site technical assistance for establishing diversion programs for food scraps and/or recyclables.

Both districts offered free waste assessments, training materials and recommended action plans for participant businesses. Recommendations addressed hauling and equipment, staff training, signage, ongoing support and free business promotion through press releases and social media. Participating businesses could also become official partners in the U.S. EPA Food Recovery Challenge.

Finding what’s already working

The site visits highlighted numerous diversion tactics currently in use by businesses. For example, some food preparation operations use vegetable scraps and poultry bones in stocks and gravy to reduce loss and save money.

In addition, many stores use close-to-expiration (but still edible) meats and produce in sandwiches and other deli items. Leftover prepared items are packaged the next day as “Grab & Go” at reduced prices. Unsold discounted prepared items are given to staff.

Similarly, several retail markets donate items close to their expiration dates, including leftover bread and baked items, to local food pantries. Indeed, since the Vermont law went into effect, food recovery around Vermont has risen substantially. In 2015, food donations were up 27 percent. Food donation increased another 40 percent between 2015 and 2016, with significant increases in donations of fruits, vegetables and frozen meat.

Tying into the local agriculture sector is also an important tactic in Vermont.

In LRSWMD, more than half of the establishments contacted had arranged for suitable food scraps (pre-consumer and old bread/pastries, for example) to be hauled by local farmers for animal feed. In smaller establishments, such as inns, employees take scraps home to feed “backyard” chickens. And one market gives leftover waxed boxes and other reusable containers to area farmers, who can use them to transport produce and for on-farm projects.

A small number of establishments, including some inns and at least one restaurant, compost on-site via “home composting” systems. And the majority of stores and restaurants in Stowe and Brattleboro have switched to compostable “to-go” containers.

Finally, Vermont is fortunate to have 10 compost operations and one anaerobic digester permitted to accept food scraps, and a growing number of businesses divert food scraps to them. WSWMD owns and operates its own compost operation, and works with area haulers to collect commercial food scraps. LRSWMD, which is currently served by local haulers/processors, is starting its own composting operation, which will be permitted to accept food scraps.

Challenges and opportunities

Conducting business outreach isn’t easy. Business representatives are busy people and connecting with the appropriate staff can be difficult, even with the mandates of Vermont’s law in place and the technical assistance being offered free of charge.

There’s also the tricky reality of tracking progress in a realm where every actor uses a variety of different diversion options.

Some businesses do an excellent job of tracking pre-consumer food waste and diversion tonnages, viewing this data as integral to promoting greater efficiency in food ordering and preparation. However, site visits indicated that such businesses were the exception – only three businesses participating in the LRSWMD program supplied this data. Also, haulers are not required to report tonnages or the number of customers participating in composting, so it’s difficult to accurately determine the percentage of food scraps being diverted.

Diverting food scraps for agriculture is an age-old practice, one that especially benefits rural and small communities. However, most such arrangements are private transactions between farmer and generator. Trying to create “collector” lists of farmers who accept food scraps for animal feed has proven very difficult. And, as more food generators seek to divert their scraps, the number of willing farm collectors may be limited.

Also, compliance with Vermont Department of Health regulations relating to food separation and on-site storage for diversion is a significant concern for business owner/managers, as is food scrap odor. As one effective solution, some haulers in Vermont provide sawdust to their customers for covering food scraps.

Finding sufficient space for on-site storage – both in the kitchen and in waste container areas outside – can be another struggle for food scrap generators, especially in older downtown areas where alleyways are frequently overcrowded.

By providing health regulation documentation on food scrap storage, insights on odor management, and creative storage ideas, on-site technical assistance can address those common concerns.

In some instances, sharing of food scrap diversion bins by two or more businesses has proven successful. Another innovative practice adopted by some haulers is the co-collection of cardboard and food scraps. While cardboard has a higher value when recycled, commingling with food scraps allows businesses to eliminate the need for separate collection bins and benefits organics processors who may have limited carbon sources.

Business waste audits, like one held by Lamoille Regional Solid Waste Management District (upper-right photo), help stakeholders know details on food diversion. Some Vermont food-service businesses make it a point to separate food scraps and send them to backyard chickens.

Haulers have also helped streamline the process and are integral in creating connections to end users. Under Vermont’s law, haulers are mandated to offer food scrap collection to commercial establishments within 20 miles of a processing facility. In communities where compost or anaerobic digestion processing is available, getting haulers on board has been fairly successful.

Some haulers, including TAM Organics, Black Dirt Farm and Grow Compost, are also processors. Black Dirt Farm and Grow Compost raise chickens as well, feeding them with some collected food scraps; remaining scraps and chicken manure are composted. Grow Compost also collects food scraps for anaerobic digestion.

Chittenden Solid Waste District (which includes Burlington, the state’s largest city) owns and operates its own compost facility, and the district works closely with area haulers to provide collection services.

Central Vermont Solid Waste District (which includes Montpelier, the capital) also provides extensive outreach and training on food scraps management. Grow Compost provides collection services and hauls materials to a privately owned compost operation in Montpelier.

Models for action

The districts’ projects have helped push forward food scrap reduction, recovery and diversion activities at many businesses. The businesses that received outreach and technical assistance to initiate programs appreciated the assistance and recommendations received.

Programs that emphasize the importance of the food scrap management hierarchy – especially reducing materials at their source and food recovery – provide models for diversion in communities with limited or no processing opportunities. Connecting with small farms and even backyard chicken raisers often provides additional opportunities for food scrap diversion.

Funding from the state’s Agency of Natural Resources was essential for the districts to successfully advance business outreach activities. The Northeast Recycling Council used its resources and a grant-funded project from the U.S. EPA Healthy Communities initiative to help the LRSWMD and the WSWMD provide technical assistance.

As these projects have demonstrated, the value of creating partnerships and developing relationships between stakeholders and interested parties cannot be underestimated. Both farmers and food scrap generators clearly benefit from diverting scraps to animal feed. And cooperation between haulers and processors in the districts helps ensure that food scrap diversion is implemented effectively.

Athena Lee Bradley is projects manager at the Northeast Recycling Council, Inc. (www.nerc.org). Through funding from a U.S. EPA Healthy Communities grant, NERC was able to provide technical assistance to both LRSWMD and WSWMD in their business outreach efforts. Special thanks to Elly Ventura with LRSWMD and Kristen Benoit with WSWMD for their input on this article.