Petrmalinak/Shutterstock

Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series on the history of the zero waste movement and its impact; see part 1 here.

Our three legacy movements — recycling, anti-incineration and zero waste — are working expeditiously to reach 90% diversion with no incineration, organics out of landfills and no toxics in our packages or products. Communities, businesses and local governments today are equipped with strategic policies and programs that were not available when the three legacy movements emerged prior to 2000.

While the movement toward zero waste gains strength and momentum, so do the economic and environmental challenges that threaten us. Consider, for example, between 2012 and 2022, Maryland energy providers spent about $100 million subsidizing trash incinerators through that state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard. A bill in the state legislature eliminates these payments and saves the state another $200 million between 2023 and 2030, according to testimony by Clean Water Action before the Maryland State Legislature in March.

With regard to our environment and nature itself, we have to eliminate the particulate emissions laden with microplastics, which represent our human fingerprints on ecological calamities. Plastic pollution, in particular, has transformed from an environmental crisis to a crisis of “critical human health,” as the recent documentary “Plastic People” makes clear. And then there are PFAS, chemicals with a virtually indestructible bond between chlorine and carbon molecules that, along with plastic, invade all of nature, including our bodies. Yet the plastics industry is telling our school children that there is nothing to worry about, as The Washington Post reported in February.

New strategies and tactics to rein in waste

The U.S. EPA has identified 100 local policies and programs that boost recycling. One of the most impactful is unit pricing or garbage metering, often called pay as you throw. Households are charged only for the waste they set out on the curb but not for recycling or composting. In practice, recycling can increase by 40% in one year. Cities adopting PAYT have reduced per capita waste generation from the US average of 4 pounds per day to less than 1 pound per day, according to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance.

Bans and rewash initiatives focused on plastic products are having a major impact on economic, environmental and social problems as well. Scores of new companies are investing in wash systems that rely on reusable tableware in numerous jurisdictions banning single use plastic products. Durable plastic and stainless steel utensils are rewashed on site or picked up, cleaned and returned to the restaurant for use. Restaurant chains, sports and entertainment venues, government cafeterias and schools are saving hundreds of thousands of dollars by switching to this new phenomenon, driven by local policy initiatives.

Venues that do not have wash facilities can obtain grants for this infrastructure from both federal programs and companies such as ReDish, RCup, Plastic Free Restaurants (and Schools), rWorld, Bold Reuse, We ReUse, and ReThink Disposables.

“We are starting to see a whole shift toward changing consumer behavior as scores of new reuse service companies are emerging,” said Chrise De Tournay, a zero waste adviser to government agencies and companies who tracks developments in this sector. “Local governments can lead the way to close the loop from one way plastic with an investment in rewash systems instead of single-use products.”

Right-to-repair laws requiring computer, automobile and farm equipment manufacturers to provide repair manuals and tools to customers and small repair businesses have been passed in 25 states.

Building deconstruction is spreading rapidly as new policies require deconstruction when buildings built before 1970 are taken down. In Baltimore, Second Chance, a nonprofit deconstruction enterprise, has 250 workers, up from six workers when they started in 2003. Around 90% of these workers are drawn from hard-to-employ people in the city and now have jobs with wages and benefits to raise a family and own a home. If the Baltimore City Council passes a bill requiring mandatory deconstruction, Second Chance CEO Mark Forster estimates that he will have to train and hire another 250 workers.

Another deconstruction company in Baltimore, Humanim, reported a zero recidivism rate for workers who were ex-offenders. The national rate for recidivism is 75%. Building deconstruction in Baltimore as elsewhere recycles people as well as building materials.

Deconstruction spread rapidly from its humble beginnings in the late 1990s as pilot projects took down World War II military barracks built with prized redwood lumber. Today the Reuse People, a deconstruction company based in San Diego, has over a dozen affiliates across the U.S. The Building Materials Reuse Association represents 32 robust for-profit, nonprofit and government programs in the U.S. and Canada.

“Deconstruction and reuse and construction and demolition recycling are on the minds of California cities and joint powers authorities triggered by new climate action plans or updates, as well as new construction and demolition waste ordinances required to meet the state’s Cal Green Code,” said Nicole Tai, owner of GreenLynx deconstruction company in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Local ordinances in cities in California, Colorado and elsewhere require a bond from companies and require them to recycle 50% or more of all construction and demolition debris to have their bond money returned. At the national level, the EPA identifies deconstruction and reuse as examples of measures to include in state climate action plans funded under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Repair and resale of consumer products through retail thrift – appliances, textiles, furniture, mattresses and books – impact environmental, economic and social issues in the communities they serve. Iconic enterprises in this field include:

- The Reuse Corridor serves the Central Appalachian regions of Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky.

- Habitat for Humanity operates 50 ReStores, which help stabilize low-income families and communities.

- Independent enterprises that fulfill the same mission include:

- Urban Ore, in Berkeley, California.

- Rebuilding Center in Portland, Oregon.

- Construction Junction in Pittsburgh.

- Community Forklift in Washington, D.C.

- The Repurpose Center in Gainesville, Florida.

- Saint Vincent de Paul of Lane County operates mattress, textile, appliance, and furniture enterprises in Eugene, Oregon. It created the Cascade Alliance, which replicated 10 new community-based enterprises across the US. Each enterprise pays hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales taxes as their workers pay wage taxes to local and state governments.

Notable enterprises like RecycleForce in Indianapolis, which repurposes discarded products from hotels, airlines and sports stadiums, and HomeBoy Enterprises in Los Angeles, which works in e-scrap, focus on people. They provide low-skilled workers a pathway away from chronic unemployment and gangs toward homeownership, stable family and community life.

LiquiDonate is a new startup that diverts returned consumer goods and excess inventory from landfills to schools and nonprofit organizations in support of local economic circularity in Canada and the U.S. Upstream just released its business reuse and circular economy start-up directories at upstreamsolutions.org.

Composting is the proverbial magic bullet for zero-waste campaigns. We are seeing Americans take to composting as we did to recycling in the 1970s. About 9% of the waste stream is now being composted, according to this year’s Composting State of Practice report by the Environmental Research & Education Foundation, United States Composting Council and Desert Research Institute, and the expectation is that this will grow rapidly.

Composting combined with food waste reduction programs can readily double the country’s recycling rate within just a few years. In addition to managing food scraps through composting – and aerobic and anaerobic digestion – food waste reduction programs are proliferating and proving highly cost effective.

The public has demanded that comprehensive, distributive composting be implemented in all parts of the U.S. When a private composting company in Wilmington, Delaware, that was serving the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area 10 years ago failed, citizens pushed for public action. Compost programs were launched in Prince George’s, Montgomery and Howard counties and in D.C. Some are robust, some are maturing, but citizen action moved the region forward.

Nine states – California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington – now have laws mandating that organics be diverted from landfill or incineration. A bill proposed in Maryland would impose a surcharge of $2 per ton on all waste landfilled or incinerated in the state. The dollars raised will be allocated in favor of small-scale composting.

In Cleveland, Rust Belt Riders demonstrates how community-based enterprises can start with collecting food discards from homes and bike trailers and grow to provide city-wide service with five trucks and 35 workers. Rust Belt Riders will host a national gathering of community-based compost enterprises and programs in October.

In New York, all large generators of organic discards must send materials to a compost facility if it is within 25 miles of the point of generation. Schools have been exempted from the regulations. Anna Giordano of We Future Cycle, Inc. is working to end that exclusion.

“Schools are large generators and there should be systemic composting and recycling programs in place, not just for financial reasons but chiefly for the educational and social benefits. Teaching students early that very small changes in daily life can make a huge difference is creating generational change,” she said.

“It was done with seatbelts, and it can surely be done with waste management and environmental awareness. And of course students will carry the recycling and composting knowledge to the entire family as curb collection programs are implemented in their towns.”

Organic materials make up 35% to 40% of the waste stream. There are year-round stable markets for finished compost and compost products in every part of the country. Quality material is valued at from $75 to $100 per ton, or three cubic yards. When applied to agriculture, compost restores eroding topsoil, conserves water and improves soil health. Economies of scale can be reached in your kitchen (vermicomposting), backyard, community and city. Composting results in a ripple effect for jobs in processing, landscaping, and nurseries and home gardening stores. Keeping organics out of landfills reduces leachate and methane gas emissions.

Anaerobic digestion facilities, which digest organic material to recover methane, also have an array of economies of scale from small units to manage manures on farms to industrial facilities. A 5,000-ton-per-year facility can digest scraps from school cafeterias, restaurant chains and entertainment venues.

There is a danger from large-scale anaerobic digestion plants. The plant coming online in Jessup, Maryland, is scaled at 120,000 tons per year. To assure that it can get sufficient materials to make a profit, the company is lobbying against programs that support smaller compost operations and farmer composting networks.

REUSE AS EMPLOYMENT AND CLIMATE POLICY

Minnesota’s reuse economy:

- Creates 45,000 jobs.

- Is valued at over $5 billion.

- Avoids carbon emissions equivalent to 100,000 gas powered vehicles.

- Could add 1,700 more jobs in electronic scrap reuse.

Source: Reuse Minnesota

FEDERAL GRANT PROGRAMS FOR ZERO WASTE:

U.S. EPA:

- Climate Pollution Reduction Grants.

- Solid Waste Infrastructure Grants.

- Recycling Education and Outreach.

- Brownfields.

- Pollution Prevention.

- Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers.

- Community Change.

U.S. Department of Agriculture:

- Composting and Food Waste Reduction.

- Urban Agriculture and Innovative Production.

U.S. Department of Energy:

- Recycle-X Competition.

- Strategy for Plastics Innovation.

- Make It Prize.

- Battery Manufacturing and Recycling.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration:

- Marine Debris Community Action Coalition.

Critical developments at the EPA

The incineration industry is aggressively fighting to protect its turf. Ongoing lobbying efforts are under way to persuade EPA to declare pyrolysis or gasification of garbage a non-incineration technology.

The public, especially environmentalists who are focused on plastic reduction, fear that incineration of plastic waste will only bring more virgin plastic pollution. Plastic particles already permeate every crack and crevice of the natural world, including our bodies. Microplastics are found in human brains and babies’ umbilical cords with unknown consequences.

Thanks to the work of the Energy Justice Network and its network of over 30 grassroots groups, the EPA has been challenged to justify its decades long claim that garbage incineration is a better waste management technique than landfilling. EJN and its network is further pressing EPA to recalculate its Waste Reduction Model, or WARM, which also has been a prop for determining that incineration is better than landfilling.

The model “gets it backwards when constantly showing results that burning trash (and landfilling ash) is better for the climate than directly landfilling trash. The opposite is true,” Energy Justice Network CEO Mike Ewall said. “Incinerators immediately shoot all of the carbon in trash into the atmosphere while much of the carbon in waste ends up stored in landfills, especially from plastics that don’t biodegrade.”

A new law in Oregon may also impact the fate of garbage incineration nationally. The justice network, working with anti-incineration forces, in Oregon succeeded in passing a requirement in 2023 that incinerators operating in the state must have continuous monitoring of emissions and report this information to the public.

By next year the landscape for incineration could change fundamentally. In late February, for example, the U.S. EPA updated the

National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Particulate Matter, tightening the standard for soot pollution from 12 to 9 micrograms per cubic meter. The EPA estimates that the new rule will save 4,200 lives, prevent 5,400 new cases of asthma and 10,000 emergency room visits and avoid 270,000 lost workdays each year.

The role of EPR

The role of EPR

It remains to be seen how recently passed extended producer responsibility laws will impact the recycling and incineration industry. Industry giants have overseen 20 years of no growth in the national recycling rate. What will the producer responsibility organizations created by EPR laws to oversee recycling and composting change? Will incineration – in cement kilns, industrial boilers and/or in pyrolysis plants – become part of a greenwashed version of zero waste? Already burning options are included in many bad EPR proposals around the U.S., such as California’s SB 54, which may include chemical recycling. An EPR bill in New York prepared by Beyond Plastics environmental group specifically excludes chemical recycling.

It all depends on whether grassroots strategies and values are written into the governing rules and regulations. The fear at the grassroots level is that corporate giants in the packaging and plastic industry can easily gain control of an EPR bureaucracy, or producer responsibility organization, and promote incineration as an acceptable management practice. This has happened in British Columbia. This would pervert the nature of EPR from a policy of polluter pays to a policy of polluter controls.

Some states are considering using consultants to manage the PRO. This also is worrisome for grassroots zero waste advocates. Why contract out for essential long-term services that require skilled public servants to manage? Building capacity and institutional memory within the public sector is essential.

Elizabeth Balkan, Director of ReLoop North America, said EPR could present a barrier to the expansion of reuse regimens.

“EPR could be used as a tool for accelerating or decelerating source reduction,” she said. “Producers will be focused on securing the cheapest possible programs, and because reuse solutions are cost-effective long-term but require significant upfront capital, they will not voluntarily make the investments.”

Balkan continued: “Developing reuse targets and incentives, as well as funding requirements, is critical to achieve system performance and source reduction. Without this, we could be locking ourselves into several more decades of a carbon-intensive toxic and polluting single use packaging economy.”

Any city or county seeking financial support for capital investment in zero-waste infrastructure and enterprises can apply to numerous federal grant programs.

Will this be enough to stop the plastic/pyrolysis onslaught?

Most recently, PFAS chemicals have drawn attention from scientists and activists in addition to well-known pollutants emanating from municipal waste incinerators. Incineration of PFAS material produces smaller versions of the chemical.

PFAS were developed in the ’40s, and by the ’70s began appearing in consumer products and eventually in nature and humans. They are manufactured mostly in the U.S. and Europe by two companies, 3M and DuPont, but are highly mobile via rain, snow and soil. The companies were “deeply aware” of the dangers, explained David Bond of the Center for the Advancement of Public Action at Bennington College during a presentation to the Westchester Alliance for Sustainable Solutions in March. Most recently, the EPA designated two PFAS compounds as hazardous substances under the federal Superfund program.

Living downstream from plastic manufacturing or military bases is dangerous, Bond has said, as PFAS contribute to an array of health problems including cancer, obesity and hypertension. Plastic manufacturing plants have proliferated in recent years in the US: 55 since 2012, with companies proposing to build 33 plants, though that number could rise, according to the Environmental Integrity Project.

Extremely low levels of exposure to PFAS can trigger these serious ailments and more. Yet the petrochemical industry is fighting back against the common-sense efforts to stop plastics from impacting the environment. The proliferation of these plants will allow the industry to produce more and more plastic. Industry is heavily lobbying to exempt this technology from all air pollution rules; incinerators are not incinerators, they claim, but rather are energy manufacturing plants. In the past few years these lobbying efforts at the state level have convinced 25 states to adopt this rebranding and make the plants eligible for public financing.

Since federal laws preempt state laws, the industry is focusing its forces on the EPA to reclassify pyrolysis. Such false rebranding would open the door to more and more plastic pollution. In addition, the industry is targeting special new tax credits for electricity generated by pyrolysis plants.

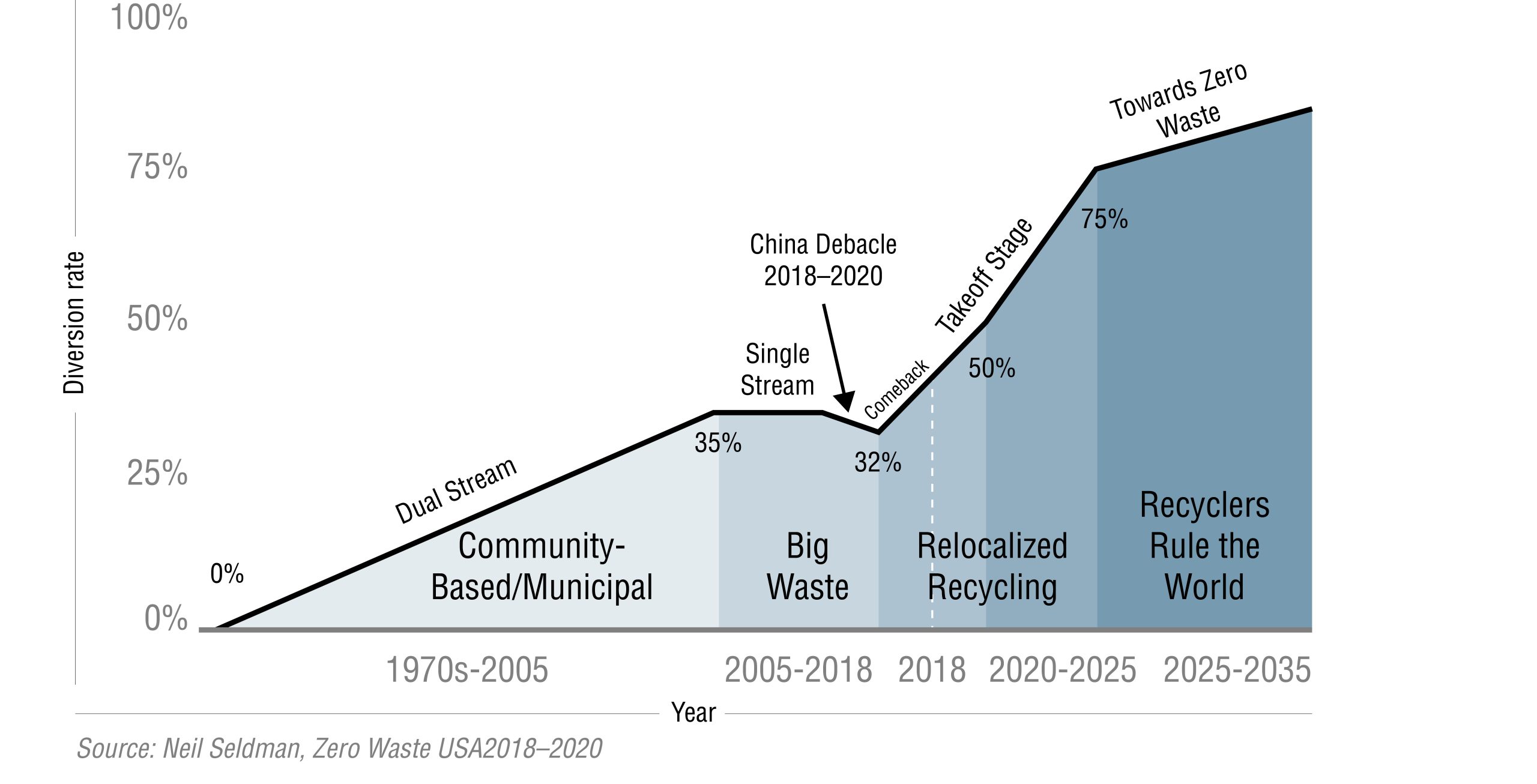

The environmental movement in the 1960s was a candle in the dark for Americans. Today, the warnings from plastic production and global warming are a burning bush. Plastic particles have entered our lungs, our brains and our babies. Global warming is leading us headlong into ecological collapse. Now is the time for grassroots activists to aggressively approach their officials to take advantage of available funds, technology and businesses to eliminate incineration and implement zero waste. We are at the take-off stage for achieving zero waste. It is within reach.

As before, we must organize at the local level to protect the gains we have already made and overcome these new challenges. Solid waste management decisions are made at the local level, where activists can secure zero waste policies and programs, and which ripple upwards into state and federal actions. We need to vote for zero waste champions to maintain and accelerate this process.

Neil Seldman is cofounder of Zero Waste USA, Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Zero Waste International Alliance and Save the Albatross Coalition. He directs the Recycling Cornucopia Program at Zero Waste USA, which provides pro bono assistance to community and environmental organizations as well as small businesses.

The role of EPR

The role of EPR