This article appeared in the April 2021 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The city of Cambridge, Mass. is known for education, being home to both Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

But when China’s National Sword sent recycling markets into turmoil several years ago, municipal officials in Cambridge had to bring knowledge-sharing out of the ivory tower and down to the curb.

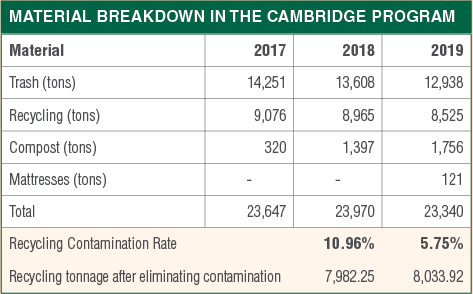

In 2018, the city of 116,000 people had a contamination rate of 11%, similar to most other communities nationwide at the time. But with downstream buyers demanding cleaner material, local MRF operator Casella Waste Systems was reworking contracts: If cities could deliver material that had a contamination rate at 7% or lower, they’d pay significantly lower processing fees.

That forced Cambridge to spring into action. It launched a campaign called “Recycle Right” in June 2018 that used a variety of messaging techniques to educate all residents about the most common contaminants. Earlier this year, Cambridge announced its 2020 contamination rate had fallen to 4%.

Michael Orr, the recycling director

for the city of Cambridge, Mass.

Resource Recycling recently talked with Michael Orr, the recycling director for the city of Cambridge, to learn more about the process of informing residents how to clean up the recycling stream.

What kinds of shifts were you seeing and hearing about in 2017 and 2018?

Michael Orr: It was a bottom-line thing for us. Our MRF contract said if we were above 7%, we’d be paying a certain rate, and if we were below 7%, we’d be paying half as much. We really hadn’t done a lot to thoroughly reduce contamination – we had just done general education and tried to get people to throw fewer plastic bags into recycling. With National Storage, we started thinking, “What is our approach to trying to re-educate the community?” We started by just gathering data, looking in bins, seeing what the top contaminants were. Just like every other community, we found out it’s plastic bags. But also we were looking at things that were just heavier – wood, e-waste, textiles, those kinds of things. Then we really just focused our campaign on targeting those top issues.

What did that campaign look like in general?

We had messaging on bus shelters and Bluebikes, which is our bike sharing program in the Boston area. The idea was to quickly just highlight the top four issues: no plastic bags, no tanglers, no e-waste, no clothing or textiles. We wanted residents to just keep those items out. Then we started cart-to-cart contamination audits, and would tag contaminated carts before the truck came around to collect. The tags would let people know that the cart was either rejected because it was too contaminated or it was collected but that they should be mindful that there was contamination. We wanted to get the education as close to the consumer as possible.

Cambridge is a fairly densely populated community very close to Boston. So I imagine multi-family buildings are a big part of the equation there. Those complexes are notoriously difficult when it comes to addressing contamination.

A lot of our constituents are multi-family. We currently service 44,500 out of 55,000 households, so basically 90% of the city, and that includes a lot of students who live in off-campus apartments. Around 75% of all apartment leases end on the exact same day: Sept. 1. So obviously we see contamination spike during that period.

How did you fold multi-family into the recent campaign?

We have a program manager who tries to check in with multi-family buildings to see how they’re doing. If we saw really bad contamination at one particular building, we would not only tag it with an “oops” tag but we would also send a mailer postcard to each unit in the building. So we were really targeting everybody in that building to say, “Hey, we’ve got to improve our recycling.” Those individual postcards I think really helped move it along. We also talked to property managers regularly and tried to keep them in the loop on things. We have a good property manager population, and they are willing to work with us.

Did you have to increase your program budget or find outside funding to engage on the campaign?

Some of the money we had already earmarked for advertising our curbside compost program, which we were launching and expanding right around this time. We have a designer on contract who could put a couple things together for the advertisements. The boots-on-the-ground stuff was really just two part-time staff working for maybe three to six months and just trying to identify as many contaminated carts as possible and quickly raise awareness of the issue. It was a combination of that and everything else we were doing at the same time. We were sending out a citywide mailer, we were doing these advertisements, and we were creating these new stickers to go on the recycling carts. We revamped our program fairly quickly in just over a year. It didn’t require a ton of resources; it just required a ton of attention.

Well, it certainly seems to have resonated with the community.

One thing that sets us apart from other communities is that we have a very progressive and attentive citizen base. Harvard and MIT are both here in Cambridge, and we’ve also got a lot of the tech companies like Google, HubSpot, Moderna and Pfizer. You have a lot of smart people in Cambridge, and I think a lot of them care about the environment. It may look like we put a ton of resources into this, but a lot of it was that our residents were willing to listen and take action.

At the same time, that is a demographic that often engages in wish- cycling. Has that been an issue for you?

Yes, we in the past have seen things like paper towels and textiles where people didn’t realize they weren’t putting it in the right place. One of the more interesting components was that at the end of 2019, we were able to review or examine our trash numbers and contamination. We thought, “If there’s less contamination, there must be more trash.” We actually saw a decrease in trash as opposed to an increase. I think that was because people were starting to learn how to properly dispose of certain items. People were going more frequently to textile bins around the city or bringing electronics to our recycle center. I think people generally were just finding ways to get rid of their waste without assuming it should just go in the recycle bin.

Cambridge has a high number of college students who live in multi-family dwellings. The city has

developed a number of recycling outreach strategies to multi-family residents.

Were there any digital outreach tools you leveraged?

We’ve got this tool on our website run by Recollect; we call it the “get rid of it right” tool. I can’t speak highly enough for that system. Residents type in the item they want to get rid of and the tool offers disposal options. There are hundreds of searches every day, which provides us with back end data to review. So, for example, if we see that people are searching “Styrofoam” at high frequencies, we know that we need to cover plastic foam in our next newsletter. We use data to better inform our decisions and take the necessary steps to make improvements where they are needed.

The city contracts with a private hauler for collection. How did you bring that entity into the effort to reduce contamination?

We implemented a new incentive for our recycling collection contractors, offering drivers bonuses based on the lower contamination that they deliver to the MRF. For example, we will offer them an extra bonus per quarter if that rate is under 7%. That way we are making sure that they are helping us identify the really bad areas. They can get their bonus and we can improve our outreach. We thought it was important to make sure that the incentive went directly to the drivers to make them feel that much closer to the shared goals. We average it out over a quarter to account for times of the year where contamination spikes.

Your campaign was wrapping up right as COVID-19 hit last year. What has the pandemic done to your contamination?

We review our numbers every three to six months, and I was shocked that the contamination rate just kept going down for 2020. To be honest, I’m not 100% sure why. I would have thought people would have gotten more lazy, but I also wonder if maybe it’s the flip side: People have more free time and they are maybe being more conscientious since they are not always rushing to get somewhere. We know that certain items like those plastic bubbles from Amazon are showing up more, but they’re so lightweight that it doesn’t really hurt our contamination numbers, which are measured by weight.

What would your advice be to other cities that are looking to generate a cleaner recycling stream?

There’s value in conducting a really large and general campaign across maybe an entire year – just to grab as much attention as possible. I think that was the most impactful part of this. It has continued to pay dividends even a year after we stopped doing it.

Dan Leif is the managing editor at Resource Recycling and can be contacted at [email protected].