With its wide open spaces and physical distance from the rest of the country, things work a little differently in Alaska.

With its wide open spaces and physical distance from the rest of the country, things work a little differently in Alaska.

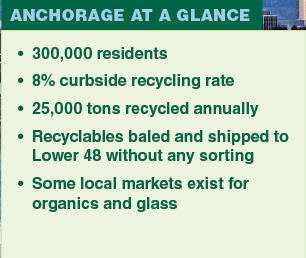

Anchorage, Alaska is home to about 300,000 residents, making up nearly half the state’s entire population. Recycling efforts have grown over the years, and the city currently operates a single-stream recycling program.

But moving the collected materials downstream has always been a bit of a task.

“Geographic isolation is our biggest challenge, for sure,” said Suzanna Caldwell, recycling coordinator for the city’s solid waste services department.

Challenges aside, the city is steadily progressing its recycling efforts and is conducting some unique outreach that communicates the value of diversion to residents.

Shipping patterns open up opportunity

Recycling in Anchorage dates back to at least the 1970s, when local volunteers would put on pop-up events collecting recyclables. Those efforts later evolved into multiple drop-off sites around the city. Eventually, a 24-hour drop-off recycling center opened.

In 2008, recycling took a major step toward convenience with the introduction of curbside recycling service. The city launched it and continues to operate it as a single-stream program. Anchorage focuses on what Caldwell described as the “big ticket items,” meaning mixed paper, cardboard, plastics Nos. 1 and 2, aluminum and steel cans. The city accepts glass through several drop-off sites but does not accept the material at the curb.

There are no recycling requirements for residents locally, and there are no state laws regarding recycling. The city handles recycling collection for about 12,000 residential households, with private haulers collecting from areas ourtside the city center.

About a quarter of city residents currently have curbside recycling service, and the city collects about 25,000 tons of recyclables per year.

The next step is moving materials to market, and that’s where the Anchorage program differs from systems in most other American cities.

“We’re really constrained by a lot of those market forces that we’re all dealing with, but we’re especially sensitive to it in Alaska,” Caldwell said.

That’s because there are virtually no end markets in the state; in fact, there are no large manufacturers at all. Furthermore, there are no materials recovery facilities (MRFs) in all of Alaska.

That’s because there are virtually no end markets in the state; in fact, there are no large manufacturers at all. Furthermore, there are no materials recovery facilities (MRFs) in all of Alaska.

All collected recyclables are delivered to a city-operated recycling center, where they are baled without any sorting.

The baled materials, contaminants and all, are taken by shipping line to MRFs in the continental U.S. The city works with a local nonprofit group that helps connect the recycling division with shipping companies. Alaska gets many of its goods shipped in on cargo ships, but the state doesn’t send ship out many products. So the Anchorage recycling program gets subsidized shipping costs for backhauling recyclables in the otherwise empty cargo lines.

Because the material is sent without any sorting, Anchorage has a particular interest in reducing contamination, and the city communicates that message to the public.

“We don’t want to ship our trash, so it’s important that we have our contamination levels under control,” Caldwell said.

Conveying the value of recycling

Anchorage has another reason to maximize diversion. The city operates the area’s only landfill, which has roughly 40 years of life left.

“We really try to remind our elected officials about how important it is to do waste reduction now and to divert materials out of the waste stream in order to keep that landfill life going,” Caldwell said. “And that has really resonated with our community.”

One way the city conveys that message is with an online tool casually referred to as the “Doomsday Clock.” It’s a running countdown showing how much time is left until the landfill will reach full capacity and will need to close.

The tool has a slider that shows how various recycling choices affect that closure date. For instance, the slider shows that if the city got rid of recycling services altogether, seven years would be cut from the landfill’s life span.

If the city reduced the amount of waste going to the landfill by 25%, on the other hand, the life of the landfill would be extended by roughly 10 years. And mandatory curbside recycling, along with diverting all organics and yard waste, would extend the landfill’s viability by more than 30 years, the tool shows.

“People really connect with it, because they can see right away the benefits of recycling to our community,” Caldwell said.

Landfill life is especially critical because expansion costs, or the cost of building a new landfill, would be substantial. Disposal costs, Caldwell said, would be five to seven times more than what they currently are.

Finding local solutions

While end market development is a hot topic throughout the continental U.S., there is less movement toward establishing end users of material in Alaska.

“It’s a small feedstock, and there are no manufacturers,” Caldwell explained. “So there’s not a ton of incentives for people to develop those end markets for certain recyclable materials.”

However, opportunities to use recyclables locally do arise.

The city has a number of glass drop-off sites and is also restarting a commercial glass collection effort. It has never penciled out economically to ship the material down to the Lower 48, Caldwell said. But the city works with a local company that will accept glass and use it as aggregate in construction materials.

Organics are also a natural fit to use locally, and the city recently started offering a curbside organics collection program for a limited number of residents. The program accepts food scraps and yard waste, materials which are handled by nearby composting operations.

But because this is Alaska, the organics program has some uncommon challenges. Residents are advised not to place their organics carts out on the curb before 7 a.m. on the morning of collection. That action, the city explains, reduces the chance of attracting bears.

Think your local program should be featured in this space? Send a note to [email protected].

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.