This story originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

When it comes to supporting the recycling of plastic materials from the waste stream, Oregon has long been active in the policy arena. In 1983, the state passed the Oregon Recycling Opportunity Act, which required that every person in the state be provided the opportunity to recycle. In 1991, the state passed its Rigid Plastic Container Law, which was designed to kick-start the recycling of plastic containers in Oregon. Today, virtually all residential programs in the state collect recyclables in a cart-based commingled format that is consistent in terms of the types of plastics collected (statistics show around 99 percent of Oregon’s community curbside programs include plastic bottles, jars, tubs and buckets up to 5 gallons).

But even with such supportive policies and operational best practices in place, large tonnages remain headed to disposal. According to an analysis by Reclay StewardEdge, the state’s approximate plastics recycling rate is 19 percent. If one includes the plastics in multi-material items such as electronics and appliances, the rate drops to 15 percent.

Clearly, more steps can be taken, and to identify additional action that could be driven by the state as well as Metro, the regional government in the Portland area, leaders recently conducted the Oregon Plastics Recovery Assessment project. The work was funded by Metro, and the project was led by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

Information for the study was gathered by the consulting team of Reclay StewardEdge and Cascadia Consulting Group during 2014, and the findings were considered by DEQ, Metro, a multi-stakeholder workgroup and the consulting team. Together, these entities developed 10 focus areas that could be practically implemented to help lift plastics recovery in Oregon in the near future.

According to the final report, released in early 2015, the 10 focus areas together have the capability of increasing plastics recovery statewide by 36,000 tons a year. In the process, the state’s plastics recycling rate could rise to 29 percent, and its net greenhouse gas emissions would drop by just under 40,000 metric tons carbon dioxide equivalent, a reduction on par with removing 8,400 passenger vehicles from roads each year. The greenhouse gas reductions come from increased recycling, which offsets virgin production, as well as avoided combustion and landfilling of plastics.

This article will lay out the specifics of the 10 identified plastics recycling focus areas as well as the methods used in determining the benefits associated with each step. Keep in mind that to reach the gains detailed in the paragraph above, all of the focus areas will need to be implemented aggressively. It’s also important to remember each strategy carries its own costs and set of obstacles.

Varying in difficulty

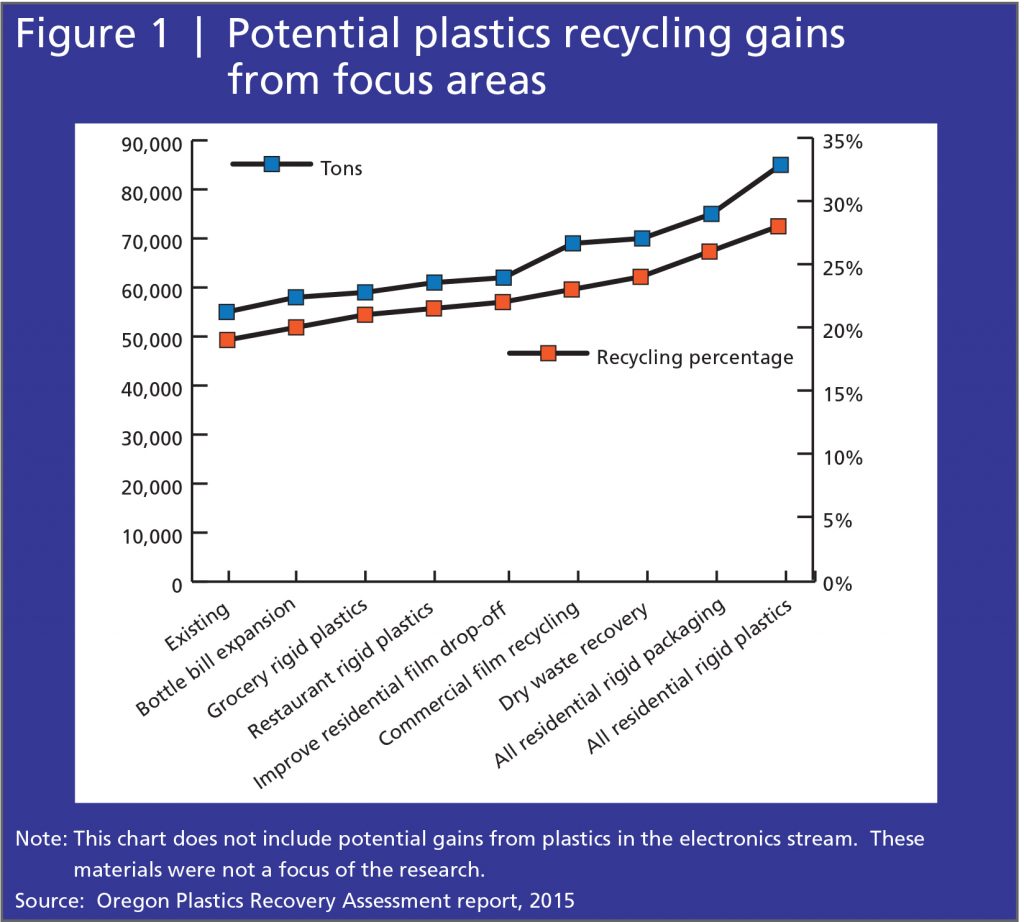

The possible avenues to enhance plastics recovery in Oregon are listed in the following paragraphs, starting with those considered easiest to implement and progressing to the more difficult-to-implement concepts. If all of these focus areas are aggressively implemented, it is estimated that recycling of plastics from Oregon could increase by nearly 70 percent over current levels (see Figure 1 on the next page). It should be noted that the focus areas are all based on recycling of plastics as plastics materials. Diversion of plastics to energy recovery was not included in the options that were considered further, based on feedback from the Plastics Recovery Assessment Advisory Workgroup and DEQ staff.

Bottle bill expansion. The passage of House Bill 3145 in 2011 paved the way for two changes to Oregon’s bottle bill that are likely to have sizable impacts on plastics recycling. Under HB 3145, Oregon’s deposit program will have to expand by 2018 to cover all beverage containers, excluding wine, liquor, milk and milk substitutes. In addition, the law automatically triggers a doubling of the nickel deposit on covered containers in the event the container recycling rate is unable to reach 80 percent for two consecutive years. The container recycling rate was 71 percent in 2013 and 68 percent in 2014.

Bottle bill expansion. The passage of House Bill 3145 in 2011 paved the way for two changes to Oregon’s bottle bill that are likely to have sizable impacts on plastics recycling. Under HB 3145, Oregon’s deposit program will have to expand by 2018 to cover all beverage containers, excluding wine, liquor, milk and milk substitutes. In addition, the law automatically triggers a doubling of the nickel deposit on covered containers in the event the container recycling rate is unable to reach 80 percent for two consecutive years. The container recycling rate was 71 percent in 2013 and 68 percent in 2014.

The expansion of covered containers and deposit increase to 10 cents per container is expected to occur without additional policy action by the state and could increase annual plastics recycling in Oregon by 2,000 tons (not including containers shifted from existing recycling programs).

Grocery rigid plastics. The second option on the list tackles rigid plastics generated by grocery stores. According to the report, 1,500 tons of clear HDPE and PP injection-molded containers and lids could be recycled with a targeted outreach and technical assistance campaign geared at both large and independent grocery stores.

The report suggests “economics for recycling these materials are often favorable.” Large grocers can add rigid plastics to the list of materials already being backhauled while smaller, independent grocers can look into including those materials in commercial commingled recycling programs.

Restaurant rigid plastics. Launching an enhanced effort to promote rigid plastics collection at restaurants could lead to an additional 2,200 tons of material being recovered in Oregon each year, the report indicates.

As with grocery stores, many restaurants are unaware of the value of rigid plastic containers and lids. Recycling companies also tend to be wary of taking in food-contaminated items. Outreach and marketing can help, the report states, as can encouraging restaurants of all types to adopt commercial commingled recycling.

Residential film drop-off. With 2,000 tons of residential plastic film and bags being collected annually in the state, the report sets a goal of recycling another 1,000 tons each year by promoting in-store recycling and enhancing recyclability labeling.

While drop-off locations for film are found at grocery stores throughout Oregon, the report states a majority of recyclable residential polyethylene film is still disposed by Oregonians. The report suggests adopting the Sustainable Packaging Coalition’s How2Recycle label to help inform residents of the recyclability of a variety of non-bag film plastics.

Commercial film recycling. Finding that a majority of commercial film is going to landfill, the report says an additional 6,600 tons of the recyclable material can be diverted in the state.

Numerous obstacles exist, including low generation rates for most businesses and fewer drop-off locations, but commercial film is also more valuable and in greater demand than residential film. By applying strategies piloted elsewhere – such as Wisconsin’s WRAP (Wrap Recycling Action Program) – and expanding grassroots outreach, the state can likely increase commercial film diversion.

Dry waste recovery. Another 1,100 tons of diversion might be achieved through encouraging MRFs sorting commercial dry waste in the three Portland metro-area counties – Multnomah, Clackamas and Washington – to sort out more plastics from incoming material streams. Metro has required since 2009 that construction, demolition and other dry waste streams be either separated for recycling or processed by a MRF to remove recyclable material such as metals, recoverable wood and cardboard. Plastics recovery has not been significantly boosted by the effort, as MRFs have concentrated on heavier materials. By focusing on sortable and recoverable plastics currently treated as residue, plastics recovery could be significantly increased, but additional plastics processing capacity may be needed to identify the different plastics and cost-effectively recycle them into marketable commodities.

All residential rigid packaging. The report suggests a major diversion bump could come by leveraging the widespread availability of commingled recycling in Oregon and including more rigid plastic packaging in the curbside mix.

All told, another 5,800 tons of that packaging type could be recovered through residential programs. To do so, the report notes major infrastructure changes will need to take place, including the development of domestic markets for mixed plastics, more optical sortation equipment at Oregon MRFs and growth in specialized plastics recovery facilities to sort and process the mixed rigid packaging stream. Those steps all carry significant costs.

All told, another 5,800 tons of that packaging type could be recovered through residential programs. To do so, the report notes major infrastructure changes will need to take place, including the development of domestic markets for mixed plastics, more optical sortation equipment at Oregon MRFs and growth in specialized plastics recovery facilities to sort and process the mixed rigid packaging stream. Those steps all carry significant costs.

All residential plastic. One of the more difficult-to-implement options presented would aim to bring non-packaging plastics such as toys, clothes hangers, laundry baskets and other items into the statewide stream. This step could divert an additional 9,700 tons of material, but it would also run up against the challenges noted in the residential rigid packaging option, namely unstable markets and a need for facilities with the ability to perform advanced sorting.

Printers and e-scrap peripherals. Oregon’s manufacturer-funded electronics recycling program, which up until last year focused on recovering only TVs and computers, on Jan. 1, 2015 began accepting printers and other electronic peripherals such as mice and keyboards.

All told, the printer and peripheral stream could yield another 2,600 tons of recovered plastics annually. A major challenge, however, exists in identifying domestic recyclers with the ability to sort the wide range of resin types found in the devices. The report recommends working with a regional plastics processor capable of handling the stream on the flake level by plastic type and grade.

All other e-plastics. An additional source of recovered plastics could be found in the rest of Oregon’s e-scrap stream. According to the report, 2,300 tons of plastics are already recovered from electronic devices each year but that number could jump by 3,700 tons if additional devices can be mined for recovered plastics.

The plastics in these products pose similar market problems as the printers and peripherals listed above. Here again the report suggests identifying an operation capable of sorting mixed shredded plastic material by type and resin. It also points to the possibility of expanding Oregon’s landfill ban on select electronics to cover smaller, more lightweight devices. Though plastics recovery from electronics is covered in the study, the project leaders have noted this stream was not the focus of the research.

Greenhouse gas implications

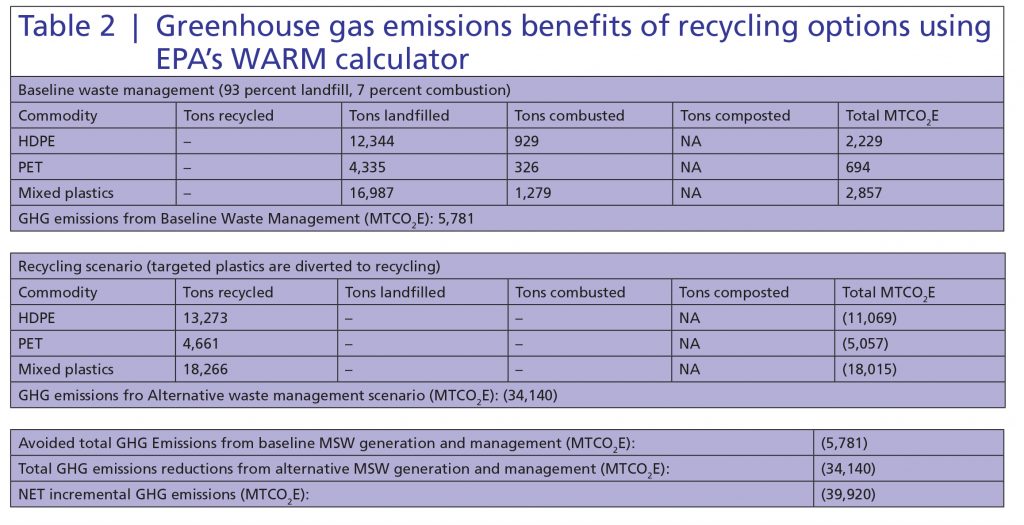

To evaluate the potential impact of increased recycling of plastics, the project team conducted an analysis using the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Waste Reduction Model (WARM). EPA developed WARM for solid waste managers to calculate the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with different waste management options. The consultants used this model and its associated emission factors to calculate the GHG emissions reductions and energy savings associated with shifting targeted plastics from their current disposal methods of landfill and combustion to recycling.

To evaluate the potential impact of increased recycling of plastics, the project team conducted an analysis using the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Waste Reduction Model (WARM). EPA developed WARM for solid waste managers to calculate the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with different waste management options. The consultants used this model and its associated emission factors to calculate the GHG emissions reductions and energy savings associated with shifting targeted plastics from their current disposal methods of landfill and combustion to recycling.

WARM makes recycling calculations for HDPE, PET and “mixed plastics.” Mixed plastics, which is calculated as 61 percent PET and 39 percent HDPE, also serves as a recommended proxy for the other plastic resins that are not currently quantified for recycling emissions and energy use.

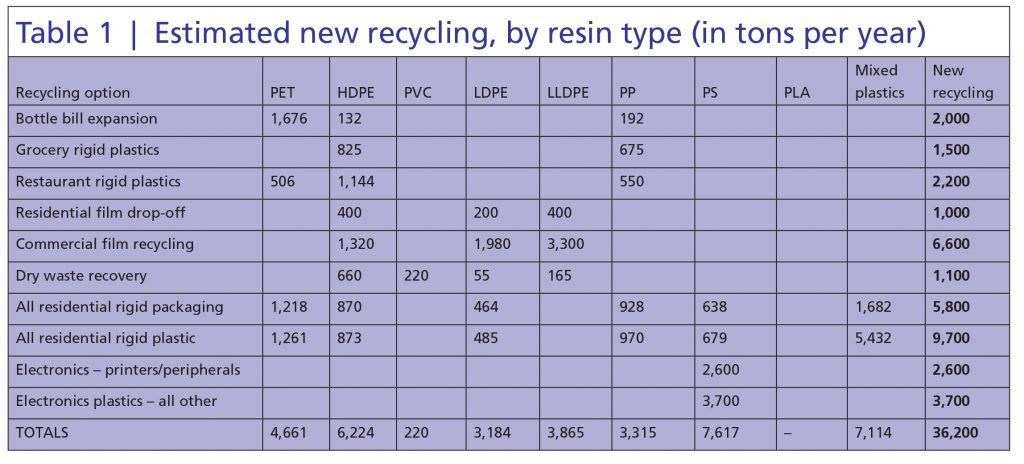

For the plastics recycling options, the team estimated the quantities and resin types shown in Table 1 on this page. PET is estimated at nearly 4,700 tons, and HDPE is estimated at more than 6,200 tons. The more than 7,000 tons of LDPE and LLDPE combined used the HDPE values as a proxy, creating a total polyethylene number of more than 13,000 tons. Mixed plastics – including PVC, PP, PS, PLA and other mixed plastics – are estimated at more than 18,000 tons when electronics plastics are included.

The results of WARM (see Table 2) clearly show the benefit of increased plastics recycling and reduced landfilling and combustion. The recycling scenarios include the 6,300 tons of electronics plastics, analyzed as mixed plastics in the model, and total additional plastics recycling of approximately 36,000 tons. By not landfilling or combusting this plastic, nearly 5,800 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCO2E) are avoided, primarily from avoided combustion. Recycling these materials saves an estimated 34,000 MTCO2E that otherwise is generated for virgin material production, for potential total avoided greenhouse gas emissions of nearly 40,000 MTCO2E.

The context of SMM

The context of SMM

The efforts to understand the overall environmental implications of plastics recycling and the steps to enhance it are particularly important to Oregon leaders because the state as a whole has begun considering waste management in the larger sustainable materials management (SMM) context. SMM aims to look at the entire life cycle of the products used within society and the impacts of all segments of the systems used to produce, transport and dispose of those items. The U.S. EPA has also begun shifting its focus to a more SMM-based model with the goals of reducing environmental impacts, conserving resources and reducing system-wide costs.

The Oregon Plastics Recycling Assessment effort was sparked by the state’s recently adopted plan, “Materials Management in Oregon: 2050 Vision and Framework for Action,” which lays out a strategy for producing and using materials more sustainably over the next three decades. In the development of that policy, plastics recovery and recycling showed great potential for helping the state holistically save energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Plastics Recycling Assessment report offers concrete steps to move forward and solidify plastic recycling’s important role in the state’s sustainability plans. In addition, it offers a useful roadmap for leaders in other jurisdictions who are working to analyze and plan their own paths ahead.

Tim Buwalda is a senior consultant at Reclay StewardEdge in Orlando, Fla. He has extensive experience consulting on plastics recovery, recycling policy analysis, and the development of recycling markets and recycling solutions for hard-to-recycle materials. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Christy Shelton, Cascadia Consulting Group principal, has 20 years of experience in design, analysis, and evaluation of effective policies and programs for resource conservation, recycling and sustainability. She can be contacted at [email protected].

The context of SMM

The context of SMM