This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Over just a few years, robotic sorting has gone from a gee-whiz laboratory curiosity to a key technology in North America’s newer and more advanced sorting facilities.

In late June, for instance, AMP Robotics unveiled the installation of six of its robots at the Single Stream Recyclers (SSR) MRF in Sarasota, Fla and noted SSR planned to install another four dual-robot systems this summer. In May, Bulk Handling Systems (BHS) sold two of its MAX-AI AQC-4 units, each with four sorting arms, to a PET recycling plant. And Plessisville, Quebec-based recycling equipment provider Machinex announced in late April that its SamurAI technology has been deployed in partnership with AMP at a Quebec MRF.

What’s more, Waste Management, North America’s largest MRF operator, in late May revealed that it’s testing robots from three different providers at its facilities.

A comprehensive analysis by Resource Recycling concludes at least 88 artificial intelligence recycling units are either working or have been purchased in the U.S. and Canada. They’re sorting residential and commercial recyclables, mixed waste, plastics, shredded electronics, and construction and demolition debris (C&D).

They are proving to be central to pulling operators through a variety of pressures, such as staffing challenges and material quality demands, that are expected to persist in the years ahead.

Showing up across the continent

The first known sorting robot to work in a U.S. recycling facility was installed only three years ago. That’s when fledgling AMP Robotics installed and tested its robot at Alpine Waste & Recycling’s Altogether MRF near Denver. Since then, other facilities have been quick to adopt the technology.

Resource Recycling compiled data from major players in the North American robots business: AMP, BHS, Machinex and ZenRobotics, and we supplemented the data with information obtained from news sources and past reports.

AMP, BHS and ZenRobotics all have units installed overseas – in Europe, Asia and Australia. This article’s analysis, however, considered only those installed in the U.S. and Canada.

Here are a few takeaways:

The technology is focused on curbside recyclables: For the most part, robots are working in single-stream MRFs. At least 39 facilities in the U.S. and Canada have robots.

Of those 39 sites, 19 are single-stream MRFs, three are mixed-waste processing sites, two are electronics processors, two are PET recyclers and two are facilities focused on C&D materials. Manufacturers would not disclose the types of streams being handled by the remaining 11 locations using robotics.

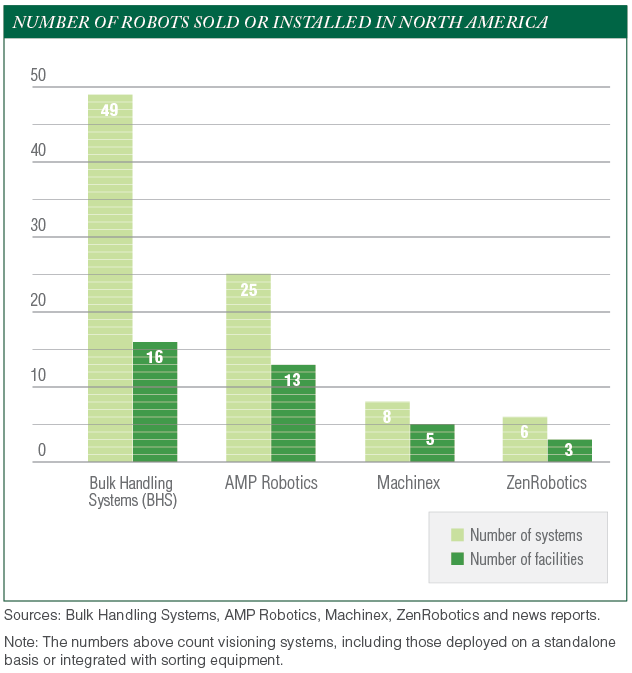

BHS has the most systems deployed: The numbers sold and set up by each company are somewhat difficult to pinpoint because installations and contract signings are ongoing. Nevertheless, we were able to develop a conservative estimate of the number of systems that have been sold or deployed in U.S. and Canadian facilities. The details are shown in the chart above.

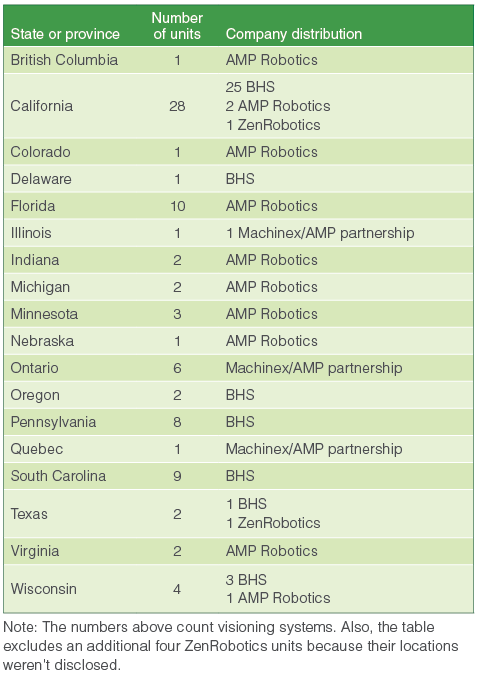

They’re all over the continent, but they especially like sunny weather: Looking at geography, the robots have been installed in 15 states and three provinces. Nearly one-third are in California, which is perhaps not surprising given the state’s sheer size, as well as policies encouraging materials diversion. See the table below for a complete rundown.

Robot providers have seen steady growth in terms of customer adoption over the past two years.

BHS announced in April 2017 that it had installed its first robot, at the Athens Services mixed-waste processing facility in Los Angeles. Now, a little over two years later, the company has sold or deployed over four dozen systems in the U.S.

It was only in mid-2018 that AMP Robotics’ system hit certain milestones for performance and reliability that gave it the confidence to go to market in a bigger way, AMP founder Matanya Horowitz said. Today, AMP has sold or installed more than two dozen systems around the country.

Also in 2018, Machinex announced a partnership with AMP through which the companies sell SamurAI robots. Today, eight SamurAIs have been installed, mostly in Canada.

Finally, in fall 2016, Finland-based ZenRobotics announced it had installed its first robot at a U.S. facility: Recon Services/973 Materials, a C&D sorting facility in Austin, Texas. ZenRobotics now has six visioning systems connected to 11 sorting arms in operation around the U.S.

And new players are still looking to break into the business. In March, Sustainable Development Technology Canada (SDTC) announced a 1.4 million Canadian dollar (nearly $1.1 million U.S.) investment in Waste Robotics, a Québec robotic sorting startup.

Chris Hawn, CEO of Machinex Technologies (a division of Quebec-based Machinex Industries), said he’s been pleased overall with the adoption of robots in North America. “As long as you never over-promise and underperform, the end result will be that the machines continue to grow in acceptance and will only get better with time,” he said.

Factors behind the trend

Factors behind the trend

The adoption by the recycling industry has come for two key reasons: persistent staffing challenges and difficult markets requiring lower processing costs and better bale quality. Also, robots aren’t prohibitively expensive, compared with some other advanced sorting equipment.

The first MRF to install a SamurAI robot was Lakeshore Recycling Systems’ Chicago-area Heartland Recycling Center, which brought on the technology in May 2018. At the time, CEO Alan Handley noted difficult fiber markets prompted the move, but he also emphasized the benefits of reducing human sorters.

Manual sorting has long been tied to staffing issues, including difficulty finding people, injuries requiring time off, and employee no-shows on any given day. The challenges are exacerbated by low unemployment rates in the current economy.

Horowitz of AMP said customers tell him that production costs and labor issues are the biggest challenges the AMP units address, he said. China’s restrictions on recyclables imports had ripple effects lowering commodities prices, he said, and a lot of people recognize robots and automation as a way to address that.

Hawn of Machinex noted sorting robots also bring other benefits in the areas of safety, separation reliability and, ultimately, optimization.

As noted earlier, Waste Management is starting to incorporate robots in its MRFs, with company leaders citing reduced labor costs, the ability to positively sort specific materials, and cleaner overall bales as benefits of using robots. The company has been testing a robot at a Houston-area MRF and is also using one at its Germantown, Wis. facility. And it plans to use a robot in a large, tech-heavy facility under construction in Chicago. During an investors summit in May, Waste Management executives said the company is testing robots at four MRFs, noting the units come from three different providers.

The benefits and costs of these systems were illustrated in the Pacific Northwest recently.

In December, Pioneer Recycling Services was awarded a grant of $284,000 from Portland, Ore.-area regional government Metro to help it incorporate robotics, and the company matched that sum.

The project involves installing two BHS robots at Pioneer’s Clackamas, Ore. MRF to sort materials on the container line. According to the company’s grant application, Pioneer plans to reduce four manual sorting positions by attrition. “If successful, the robots will make more picks of their target and prioritized commodities than a human sorter can accomplish,” according to the 2018 grant application.

The grant document notes the BHS MAX-AI AQC-1 units each cost $200,000. That does not include installation, freight, electrical and other costs, which, in Pioneer’s case, totalled about $169,000.

A newer facility can often have lower installation costs, MRF experts have noted.

Ongoing evolution

As fast as the robots are being sold and installed, the technology and its applications are also quickly changing.

Recycling robots started as visioning systems connected to mechanical arms that use suction or a gripper to pluck items off the belt and drop them in a chute. While that’s still essentially what most of them do, some MRFs are now using visioning systems independent of mechanical sorting arms. AMP calls its vision framework Neuron, and BHS calls its system VIS (short for “visual identification system”).

Horowitz explained the visioning system can help facilities conduct waste characterization studies for less cost than bringing in an audit crew to break bales, separate items and weigh materials. They also provide key operations feedback, he noted, including warnings of surges or a dearth of material on the line.

Rich Reardon of Eugene, Ore.-based BHS said his company has customers using VIS to meet their contractual audit obligations. Even if a human-powered audit is conducted quarterly, it can’t provide the kind of accurate picture of a materials stream on an ongoing basis that a visioning system can, said Reardon, who is vice president of sales and marketing for BHS.

One plant in Norway is even using a BHS visioning system to examine fiber on its way to a bunker before it’s baled. “They’re the only company I’m aware of that’ll know exactly what’s going into their bale before they bale it,” Reardon said.

AMP and BHS have both also worked to boost the sorting capacity of their products.

In May, AMP announced the release of its AMP Cortex dual-robot system (DRS), which uses two arms with a combined capability of 160 picks per minute. The company says the system is ideally suited for helping MRFs tackle fiber streams.

Earlier, BHS had developed MAX-AI Autonomous Quality Control (AQC) units with four sorting arms, each linked to a different VIS. In May, BHS sold two AQC-4 units (the “4” denotes four arms) to an unnamed PET reclaimer in Southern California.

Meanwhile, Machinex recently installed a unit with one visioning system and two sorting arms at the Sani-Éco MRF in Granby, Quebec.

Another recent innovation has been the integration of the VIS with optical sorters. From early on, representatives at robot companies emphasized their systems won’t replace optical sorters, which can still perform up to 15 times the number of picks per minute that a robotic arm can. But the visioning systems – the heart of the AI robot revolution – are being used to make optical sorters smarter.

For example, BHS has two customers in Pennsylvania and one in the San Francisco region using VIS systems integrated with SpydIR optical sorters from National Recovery Technologies (NRT), a BHS company. One of those is York, Pa. MRF operator Penn Waste, which uses the VIS on an optical sorter ejecting small OCC at the beginning of the container line. The vision system distinguishes between a paper label on a bottle and cardboard. It can then tell the optical sorter not to fire on the bottle.

The physical sorting units have also undergone innovation. BHS has developed what it calls the AQC-C, which contains one or more collaborative robots, called CoBots. The difference from earlier offerings is the CoBot is designed to work alongside human sorters, reducing the need to retrofit lines and allowing it to be installed quickly. If a human sorter bumps the arm of a CoBot, the robotic arm immediately stops moving.

“Unlike the AQC, which needs more structure to support the robot and guard employees, the AQC-C can be installed in sort cabins, on narrow walkways and in other tight locations,” according to a BHS press release.

The trade-off is the CoBots, which are “selective compliance articulated robot arm” (SCARA) units, aren’t as fast as the delta-type robots that have been used by AMP and BHS. Each CoBot arm is capable of 40 picks per minute. For comparison, the AQC-2 units slated to be installed at CarbonLite’s PET recycling plant under construction in eastern Pennsylvania are each capable of up to 60 picks per minute.

Moving into new roles

Robots have largely been deployed on quality control lines, where ample spacing between materials on the belt and a lower overall volume have allowed them to work effectively.

But Horowitz of AMP sees potential for much greater market penetration in MRFs; he estimates his company can automated three-quarters of the positions on a line. But the presort area presents problems.

On a MRF’s presort line, greater material depth and high levels of commingling have been impediments to robots. A human can quickly brush aside paper to get at the bag or textile contamination below, but that’s not practical for a robotic arm.

One solution may be in redesigning presort lines. Reardon said BHS has installed presort lines designed to accommodate the future installation of a robot. One system was designed with screens to provide pre-sizing, and the screen “unders” go to a belt where a robot could be installed.

Robots could also be integrated into other roles, such as automated loading of a system, Reardon noted. “The demand of the market is really any place where human labor is necessary,” he said.

Already, robots have moved well outside the municipal recycling sphere. Over the last several months, AMP has installed sorting robots at two electronics recycling facilities owned by ERI, a nationwide IT asset disposition and e-scrap recycling company.

One of the big challenges in adapting the robot to handle shredded electronics was modifying the sorting arm, Horowitz explained. Small, folded and fractured pieces of shredded material present unique challenges in terms of securing a good vacuum grip and ensuring the suction cup is durable.

Electronics recycling isn’t the only sector robots are invading.

ZenRobotics began in the C&D sorting space but is now also offering a system for sorting curbside materials. Of its six confirmed robotic systems deployed in the U.S., five are sorting C&D or other bulky materials and one is sorting household recyclables.

Meanwhile, AMP, which started by tackling residential recyclables, is moving into the C&D space, with AMP and Japanese company Ryohshin co-developing a robotic system for C&D debris. Two units have been installed in Japan, and AMP plans to market the technology in North America.

By starting in residential recyclables, AMP began with the toughest challenge, Horowitz said. Heavily burdened MRF container lines present not only a huge variety of materials but also problematic items such as bags, which gum up equipment. AMP has found that, in many ways, other streams are easier because they’re more consistent, he said. AMP is exploring still other applications, including organics and automotive scrap sorting.

The same goes for BHS and Machinex. Both Hawn of Machinex and Reardon of BHS said they see opportunities in e-scrap, C&D debris and elsewhere.

Horowitz said his early predictions of how robots could improve recycling have proven true.

“We’ve been really fortunate to see a lot of industry demand come out of it,” said AMP’s Horowitz. “We always thought the robots would be a big deal for recycling, but the quick uptake of the systems has been … a rewarding surprise for me personally.”

Jared Paben is the associate editor of Resource Recycling. He can be contacted at [email protected]