This story originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The growth of plastics recycling since its infancy in the early 1980s has been remarkable.

Back in those early days, there were no post-consumer HDPE reclaimers and Wellman Industries was the only vertically integrated PET reclaimer. St. Jude Polymer was a buyer too, but beyond that, few outlets for material existed.

Recovery of plastics grew over time, however. For example, in 1996, the recycling rate report on PET from the National Association for PET Container Resources (NAPCOR) showed close to 700 million pounds of PET bottles were collected for recycling. By 2015, it was approximately 1.8 billion pounds. Other post-consumer resin recycling saw similar upticks, and more plastic materials – including non-bottle containers, film and wraps, foam, and non-film flexibles such as woven bags – were added to recycling collection programs.

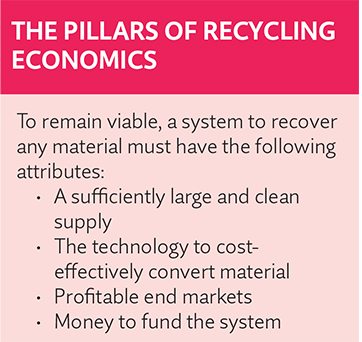

To explain what fueled this expansion, we need only go back to the basics. As Dave Cornell, technical consultant to The Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR), has taught us, plastic recycling – and recycling of any material – needs four things to succeed: a sufficiently large and clean supply, the technology to cost-effectively convert material, profitable end markets, and money to fund the system.

In the three decades Moore Recycling Associates (now called More Recycling) has been part of the industry, the power of those fundamentals has been demonstrated time and again. And by looking back at the ways the economic truths have manifested themselves, the industry can learn what underpins success as packaging evolves and sustainable materials management thinking guides corporate and governmental decision-making.

Supply-side realities

Moore Recycling’s first two projects after the consultancy’s founding in 1989 involved producer responsibility programs – one was a success, the other a failure. Both outcomes were determined by supply characteristics.

The Plastic Recycling Corporation of New Jersey (PRCNJ) is likely the most successful producer responsibility program about which you’ve never heard. The nonprofit group was developed by the carbonated beverage industry after New Jersey passed recycling legislation that required PET soft drink bottles to be recycled at the same rates as glass and aluminum or they would be subject to a PET-only deposit program. Somewhat similar to today’s Carton Council, PRCNJ worked with local and state officials to integrate PET recycling into existing recycling programs by providing technical assistance as well as market lists and purchasing equipment needed to collect and prepare PET for the market.

When PRCNJ started, there were only three towns in New Jersey that collected PET for recycling. By the time the organization ceased business (yes, it was the very rare organization that had a mission, accomplished it and wrapped up), every county and well over 90 percent of the communities in the state collected PET. The education and planning elements of the program produced a reliable supply of valuable material, and that reality set the stage for stability and growth.

In contrast, the National Polystyrene Recycling Company (NPRC) had a very public decline. It started in 1989 with the specific mission of recycling food-service foam polystyrene (PS), and received significant capital funding. But it only collected used food-service foam PS at drop-off programs, meaning it was taking in the lowest quality foam and at low volumes. Ultimately, the effort could not gain traction.

Today, another PS collection project is being undertaken by Dart Container and Indianapolis-based Plastics Recycling, Inc. Those partners are targeting curbside-collected material and all PS – rigid and foam, not just food-service items. The material types are baled together using existing equipment to make full truckload quantities. For this reason, the program has a much stronger likelihood of long-term success than its predecessor did.

These examples underline the fact that recycling cannot exist without sufficient supply at a sufficient quality level. In fact, when we look at the overall growth of PET reclamation over the past three decades, we see it stemmed from a growing supply generated through carbonated beverage bottle deposit programs and budding municipal recycling programs.

The traits of successful reclaimers

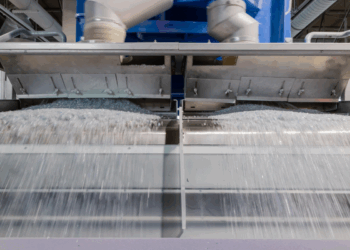

Garnering quality material is of course only the first step. Next is the importance of cost-effectively transforming that plastic into buyer-ready product, a fundamental that has consistently evolved at the reclaimer level.

Successful reclaimers share many traits. On the whole, vertically integrated facilities are much more likely to succeed because integration takes cost out of the system at each step: collection, processing and end use. In contrast, merchant reclaimers (those that only make plastic pellets or flake but not a product) are less likely to flourish, especially in poor market conditions. Those that have done so have been adaptable.

Furthermore, long-standing reclaimers show an incredible amount of versatility throughout changes in both supply and end-market demand. Envision Plastics’ color sorting capabilities and advancements in the production of food-grade resin, for instance, provided competitive advantages. Meanwhile, KW Plastics Recycling has a knack for seeing a supply of feedstock with growth potential, identifying end markets and expanding beyond its core feedstock. In 2012, KW began buying tubs and lids (think yogurt packaging), leading to a significant uptick in the collection of polypropylene (PP).

All established reclaimers make regular investment in technology, upgrading systems as new, better equipment becomes available. Thirty years ago very few facilities had resin identification equipment – most relied on hand sorting. Today it is essential to have a network of auto-sort hardware as well as a regular employee training program so that workers understand the changes in the stream over time and spot problems before they end up in the finished product.

Along with training, every successful conversion program has vigorous data collection on input material – profitable reclaimers know the quality level of each of their suppliers, pay accordingly and provide feedback to maintain consistent supplies. This has become more prominent and easier to do with the advent of graded plastic bale specifications started by NAPCOR and picked up by APR. KW has taken this concept to the inevitable apotheosis by paying for PP bales based on their yield, and the industry is likely to see more reclaimers follow in those footsteps.

By understanding and adapting to the market, reclaimers push forward the conversion process, opening up new pathways in terms of what can be collected on one end and what can be turned into new products on the other.

By understanding and adapting to the market, reclaimers push forward the conversion process, opening up new pathways in terms of what can be collected on one end and what can be turned into new products on the other.

End-market understandings

While reclaimer development can help spawn markets for material, the resin-demand realm has itself shifted in ways that have had major impacts on the larger plastics recycling arena.

Perhaps the most powerful factor in the continued development of markets has been Asia’s appetite for plastics. Non-bottle recycling was especially influenced by the strong market for low-cost raw material as China’s economy grew dramatically in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Shipping scrap plastic to China made economic sense because, at the time, the country had an abundance of low-cost labor and limited environmental regulations. Chinese buyers were able to take a mixed grade and convert it when there were few, if any, U.S. reclaimers of mixed post-consumer non-bottle material. This created a commodity that had not existed before.

However, as China’s economic and regulatory environment changed, domestic users were able to compete and mixed resin grades now have both domestic and export demand.

One example of domestic market development can be seen in the composite decking industry. In 1996, Mobil Chemical Company invested in the technology to produce composite decking made with recycled plastic bags. Trex Company was formed after a buyout of the Mobil division that owned the technology. Meanwhile, AERT, another larger composite decking company that uses scrap plastic bags and wood as feedstock, entered into a joint development agreement with Dow Chemical in the early 1990s for the purpose of developing polyethylene film recycling technology.

However, the low-scrap-value environment of the last few years put a damper on growth. Although some scrap pricing appears to be emerging from the doldrums, true recovery will require creative thinking. Here again, we return to fundamentals: Without markets that will take in material at profitable price points, recycling cannot happen.

How can this demand be stimulated? The greatest pressure to use post-consumer plastics is in packaging, but that is often the least appropriate use – packaging applications generally have the highest processing cost, particularly when plastics are to be used in very thin flexible packages. Companies producing innovative and sometimes difficult-to-recycle packaging should consider purchasing other products with recycled content, specifically products that contain recycled resin made from their consumer packaging, such as bulk containers, pallets, totes, carts, drums and other reusable transport packaging.

For now, we need to identify suitable applications that can readily absorb large amounts of PCR and provide consumer product companies credit for purchasing those products. It really is fundamentally an economic challenge, and to continue ongoing recycling growth, end-use demand must pull material effectively through the recycling system.

Surviving volatile markets

As APR’s Cornell noted, plastics recycling needs a funding mechanism to fuel the entire sector. Over the decades, the industry has grown because prices for material have been able to produce profits, and investment and innovation have flowed from there.

However, scrap material pricing is volatile and difficult to predict, a fact that has been all too real for many industry entities of late. Last year plastic converters could source virgin resin at prices seen more frequently in the 1990s. Most other costs, such as labor, are higher now and reclaimers are feeling a real squeeze trying to produce recycled resin at costs below those of virgin.

The price of plastic scrap is affected by many things, beginning with the price of natural gas, petroleum and their derivatives. But it’s important to understand that recycled plastic does not directly match petroleum pricing – it is also influenced by available virgin resin production capacity relative to demand. For instance, the PET market is currently marked by low prices due to a vast overcapacity of virgin resin production, predominantly from Asia.

In addition, industrial scrap and off-spec material are both direct competitors of post-consumer material: When they are more plentiful, scrap pricing drops. It is not uncommon to see more “off-spec” material available when there is an overabundance of virgin resin in the marketplace. Lastly, general economic conditions and currency exchange rates have an impact on scrap pricing, and the strong dollar has put a damper on plastic scrap exports in recent years.

Most reclaimers – especially the larger and vertically integrated facilities – have been able to survive thus far, but some smaller or lower-margin facilities have closed and many more are under severe financial pressure.

Fortunately, there are considerations and adjustments to be made to help ensure business continues, even amid the sway of larger economic forces.

One area where clarity has grown is in pricing. We are encouraged by the growing reliability of plastic scrap information on the scrap tracking site recyclingmarkets.net. It is recognized by government agencies, and increased reclaimer participation has improved its accuracy. This resource is enabling recycling operators to make more informed pricing decisions and navigate the market more efficiently.

One major key to successfully moving through today’s price storm is continued development of one of the fundamentals noted earlier: end-user demand. Expected growth in capacity for virgin resin, especially polyethylene, will be difficult to offset, but there are ways recycled material can stay competitive.

New technology often reduces the cost to process scrap plastic to help drive the cost to process below the cost of virgin scrap. Without a lower-than-virgin cost, plastic recycling will not succeed unless there are ongoing subsidies, such as recycled content legislation, or long-term industry purchase commitments. As the value of scrap plastic increases, we expect significant investment in sorting capabilities and preprocessing. But technology is hindered by low-value feedstock. It is critical to establish new end uses and initiate innovations in technology.

Guidance as industry evolves

We recycle to save resources and energy while reducing the toxic load on the environment. Our public policy should reflect those critical goals. With leaders like the state of Oregon adopting sustainable materials management (SMM) over weight-based diversion goals, we see real potential to tie recycled material usage to greenhouse gas reduction goals. Recycling only as an end-of-life strategy is flawed – our goal should be to grow plastic recycling by using recycled content in appropriate, energy-saving end markets.

As we move forward into this era of SMM thinking, we should not forget the four economic principles outlined above. The plastics recycling industry has made considerable progress over the past 30 years, and we believe that the innovation to date has the potential to carry us forward into SMM. Generators, collectors, processors and end users need to feel the reward of smart materials moving through an efficient system.

Post-consumer plastics are a long way from competing with the highly engineered resins used in many flexible films and other packaging applications that offer undeniable energy savings over heavier alternatives. With more complex packaging comes more complex solutions. It is unlikely we will see the investments from resin companies into recycled resin that we saw in the 1990s. But with the lessons learned, perhaps we will see other necessary investments – and as potential opportunities come to the industry, stakeholders will know the fundamental points to keep in mind when designing the programs and companies at the center of future recovery initiatives.

Patty Moore is the founder of Moore Recycling Associates, a company that is changing its name to More Recycling as Moore scales back her involvement in the industry and Nina Bellucci Butler takes over as CEO. Moore, who will continue as a contract consultant with More Recycling and as president of Sustainable Materials Management of California, can be contacted at [email protected]. Butler can be contacted at [email protected].