This story originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of Resource Recycling.

When it comes to plastic bag policy, it isn’t about the tons, or necessarily about recycling.

Used plastic bags do not add up to a large percent of the weight of municipal waste streams. However, cities – and whole countries – are increasingly taking action on plastic bags because of a range of impacts, including litter concerns, the marine plastic problem and the fact that plastic film can clog equipment at materials recovery facilities (MRFs) – this equipment issue can cause costs to rise for recycling programs.

As cities and states continue to weigh their options on bans and fees for plastic bags, it’s worth looking at the landscape as a whole to understand exactly how communities have approached the subject up until now and to grasp the life-cycle realities of plastic bag alternatives.

An item that ends up everywhere

It’s not surprising that bag management problems arise when you consider the sheer numbers. For something invented in 1977, the use of plastic bags is remarkable – it’s estimated that 400 bags are used per second in California, 500 billion to 1 trillion are used per year worldwide, and 1,500 are used per family annually. Overall, these products account for possibly 8 percent of oil output globally.

Concerns about plastic bags include the following:

- Bags are one of the primary items contributing to litter on land and trees (8 to 25 percent of litter by some accounts) and the associated aesthetics and cleanup costs.

- They also contribute to litter in waterways and the ocean – a gyre twice the size of Texas exists in the ocean, and recent reports indicate there are 46,000 pieces of floating plastic per square mile of ocean globally.

- Bags have a short “duty cycle” (most are only used for an hour or two but have a lifetime of over 100 years).

- The production of the products contributes to greenhouse gas issues.

- Bags have an impact on animals and wildlife, including the food chain.

- The items clog MRF processing equipment.

- They also clog wastewater grates that exacerbate flooding.

- They pose a risk to the human food chain via chemical ingestion.

- There are groundwater impacts from plastic bag pollution.

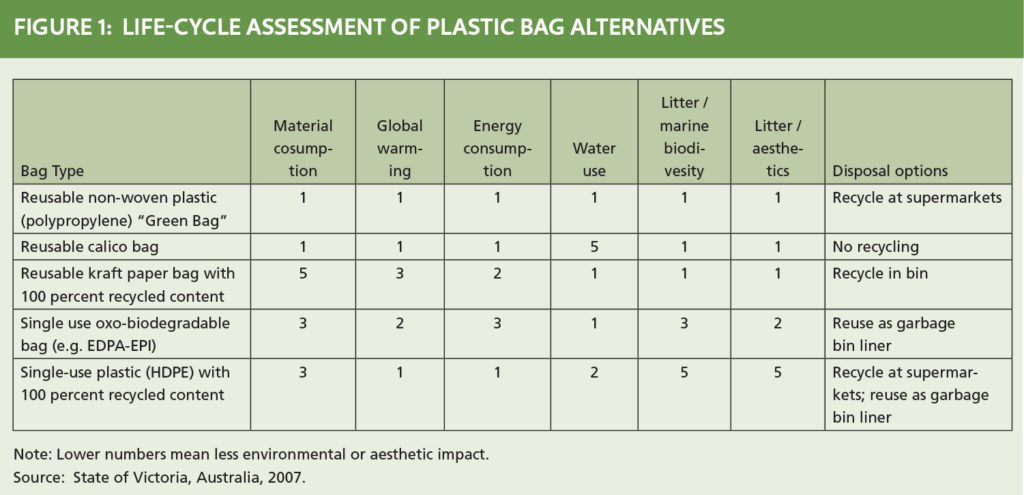

At the same time, a number of substitutes for the products exist, which explains why initiatives to curb plastic bag use have been successful in some places. How those substitutes compare with traditional plastic bags on a life-cycle assessment level is demonstrated in Figure 1 below, which shows the results of a report compiled by Rae Dilli for the Australian state of Victoria in 2007.

The Australian research ranked five different bag options and scored each across a number of different criteria, including material consumption, global warming impact and litter. Lower numbers in each category equated to less environmental or aesthetic impact. In the testing, a reusable non-woven polypropylene bag received a 1 – the best score possible – in all categories. As the figure shows, other bag options scored well in some categories, but no others notched a 1 in every column.

And what about paper bags? They are highly recycled (80 percent versus about 5 percent for plastic bags), and they also can be composted. Paper decomposes quickly and completely, but plastic can more easily be reused. Paper is also a visible employer, and mills want recycled bags. It’s important to note, however, that some life-cycle assessments recommend plastic slightly over paper because there are fewer airborne emissions and lower energy use in plastic bag production. One such study was published by Franklin Associates in 1990.

Plastic bags may be made of bioplastics or be biodegradable or compostable (decomposing into humus). Biodegradables contaminate recycling and compost batches, break down into tiny pieces of plastics, and don’t degrade in a landfill. Bioplastics are made from organics, and, along with compostables, may take several cycles to compost – they look unsightly in compost products if not fully processed. However, particularly troublesome is that these different types of bags are not easily distinguished by sight, and the plastic versions can easily become a contaminant in a composting load.

Are bans or fees better?

Bans are popular with many environmentally minded residents, and the method quickly reduces bag use (and associated litter and animal impacts) quickly. They are also simple to administer.

Backers of the fee approach, however, note that you achieve nearly all the reduction benefits from a bag fee that you would with a bag ban, but with the fee you also develop a revenue source – for both the community and potentially for retailers. Most importantly, the fee strategy preserves the element of customer choice, which can help reduce complaints. However, note that some individuals and groups oppose fees because they liken them to taxes.

Backers of the fee approach, however, note that you achieve nearly all the reduction benefits from a bag fee that you would with a bag ban, but with the fee you also develop a revenue source – for both the community and potentially for retailers. Most importantly, the fee strategy preserves the element of customer choice, which can help reduce complaints. However, note that some individuals and groups oppose fees because they liken them to taxes.

The plastics industry is strongly opposed to both the ban and fee approaches, and local communities sometimes fear that shoppers will go to the next town.

Some opposition also stems from concern that fees hurt poor households. Many communities have responded by using some of the revenues generated by fees to buy reusable bags and make them available to residents.

Despite challenges and opposition, bag policy has a history that goes back decades.

One of the first implementers was Denmark. In 1993, the country passed a bag tax on manufacturers, and the financial component was passed on to retailers and consumers – use reportedly dropped by 60 percent. Ireland was the first to charge households directly, in 2002, and the 15 euro cent fee led to a 90 percent decrease in bag use in five months. In the EU, member states are taking similar measures to reduce use by 80 percent by 2019. And bans exist in different areas of Africa, Asia, Australia and South America.

In the U.S., Washington D.C.’s early nickel fee led to an 80 percent decrease in use. Seattle in 2011 successfully passed a plastic bag ban and 5-cent fee on paper that has a sunset/revisit element. Plastic bans are also in place in several communities around Seattle. Colorado also has a number of programs, with the interest spreading from mountain resort communities. Local programs are in place in California, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Oregon and Texas. Finally, California lawmakers have pushed through a statewide ban on the product – at press time, the question of whether to implement the ban was set to be put in front of voters after the plastics industry got the issue onto the 2016 ballot.

The specifics of the policies

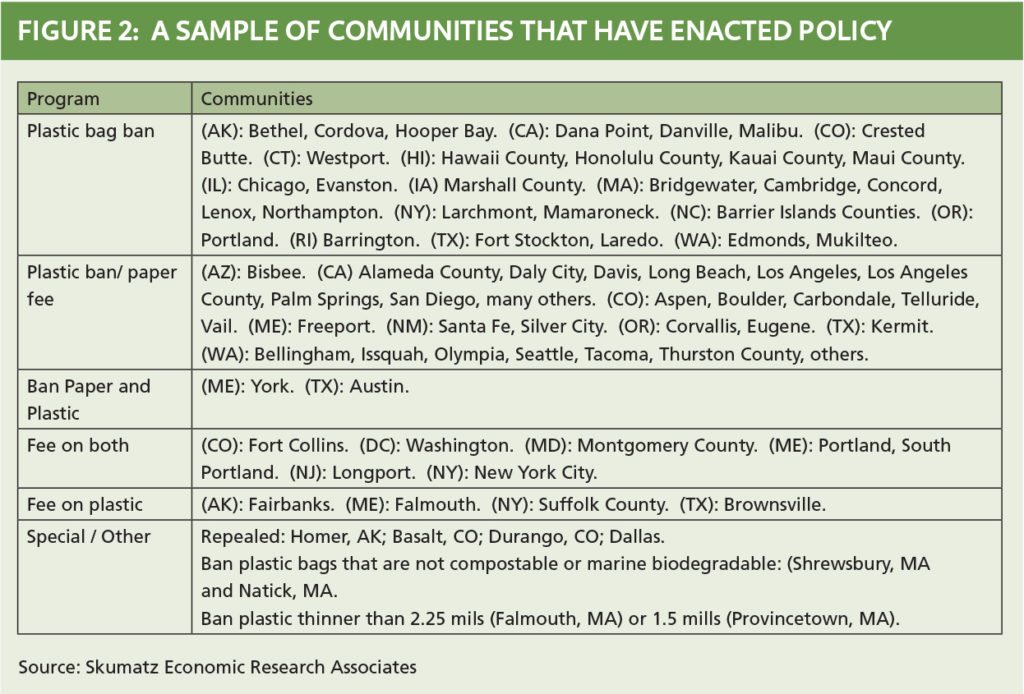

Almost all communities implementing bag laws have done so in one of five formats: plastic bag bans; plastic bans with a paper fee; a ban of both paper and plastic bags; a fee on both; or a fee on plastic. Example communities are provided in Figure 2 above.

There are two keys to a successful program.

The first is having well-designed exemptions in place. Where there are only poor substitutes for plastic bags, allowing exemptions is critical. Common exemptions include dry cleaner bags, dog waste bags, very large bags and marijuana baggies (the authors live in Colorado).

Good partnerships are also vital. Because single-use bag programs are not really about recycling and tonnages, natural allies extend beyond the “usual suspects.” Hunters, waterway associations and even grocery associations and retailers (in some cases) have all gotten behind policies in different areas. Appealing with multiple messages recognizing multiple constituencies and interest is critical. Washington, D.C.’s program was a success because of partnerships and because the measure had to have almost all councilmembers be co-sponsors and backers before the measure was ever introduced. Recycling was not mentioned.

In addition, it may be wise for communities to use long-term advertising on local problems caused by single-use bags to generate support for initiatives. Political steps can also include handing out reusable bags to low income neighborhoods and engaging grass roots groups, especially student organizations. Some communities have started by rolling out bans or fees at grocery stores, later adding drug stores and convenience stores for efficiency and administrative reasons. Others start at the largest stores first.

Most fees are set around 3 to 10 cents per bag, and usage drops between 70 to 90 percent are commonly reported. A few U.S. cities have charges as high as 20 cents per bag.

And of course not every program goes according to plan. Mexico City’s ban was repealed after pressure from plastic manufacturers, and Seattle got its program implemented only after an earlier one was rejected by city voters.

Conclusions

Bag fees and bans are popular, and have been instituted with a broad array of goals and rationales that do not center around tons. One unique motivation can be seen in the Asian country of Bhutan, which banned plastic bags in 1999 as part of the kingdom’s effort to increase the “gross national happiness” indicator.

Whether a bag ban can cause increases in happiness is a question, but we do know better how to answer the “paper or plastic” question. Respond with a resounding, “Neither, I brought my own!”

Lisa Skumatz and Dana D’Souza work for Skumatz Economic Research Associates (SERA), a research and consulting firm with clients around the U.S. and Canada. SERA assists clients with a variety of materials management programs, including program evaluation, benchmarking, cost modeling and more. They can be reached at 303-494-1178 or [email protected].