This story originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Plastics Recycling Update. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The first thing that comes up in any conversation about e-plastics is the inherent complexity of the stream. The resins in question, the downstream markets for the material and the way plastics are used in today’s electronic devices – all are marked by nuance and complications.

It’s no surprise then that successfully pulling plastics out of the electronics recycling stream is far from straightforward. Sorting, recycling and marketing the plastics content in end-of-life devices can be painstaking, not to mention economically challenging.

“Your average plastics recycler wants nothing to do with it,” said Andrew Rubin, president of FCM Recycling, a Canadian electronics recycling company that recently invested heavily in infrastructure to recover e-plastics.

However, despite the difficulties, it’s becoming increasingly important for the plastics recycling industry to try to move forward in this realm because plastics usage in electronics is rising rapidly. As a recent report from the Plastics Industry Association highlighted, the material is a favorite among original equipment manufacturers.

“Across the consumer electronics spectrum, plastics offers benefits no other material can replicate,” the report states.

To help plastics industry entities better understand the e-plastics world, we checked in with a number of companies that are handling recovered electronics everyday to get a look at the emerging trends on the plastics side – and to better understand the processes and thinking that may lead to e-plastics progress.

Tough to track total tonnages

One of the overarching challenges in the e-plastics recycling realm is the absence of comprehensive data. The U.S. EPA does not currently track the generation or recovery of plastics found in consumer electronics, and individual state electronics recycling programs rarely require recycling companies to report on e-plastics recovery.

What we do know is there’s a lot of it out there. According to a 2016 study from the National Center for Electronics Recycling (NCER), just over 2.1 billion pounds of electronics ended up in the U.S. waste stream in 2015. While the report did not detail how much of that material consisted of e-plastics, it provided a telling breakdown of the plastics content in your typical end-of-life device.

According to the report, by weight a typical CRT device hitting the waste stream contains approximately 12 to 15 percent e-plastics while flat screen devices are made up of 20 to 24 percent e-plastics. About half of the weight of a printer comes from its e-plastics content, the report shows, and keyboards and mice are made up of more than 80 percent e-plastics.

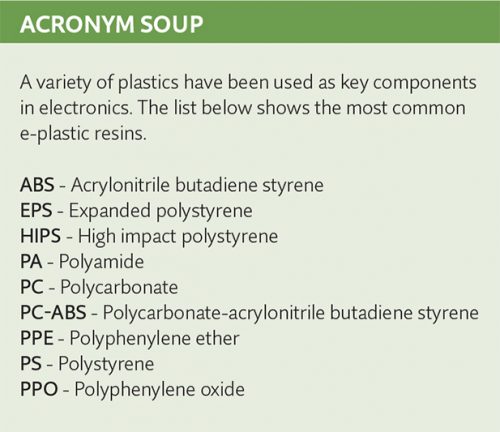

Over the years, an increasingly wide range of plastics have been used in consumer electronics, including acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), high impact polystyrene (HIPS) and expanded polystyrene (EPS) (See Sidebar 1 for an e-plastics glossary).

But not all devices utilize the same resins. According to Tom Bolon, the president of Columbus, Ohio-based Novotec Recycling, CRT monitor housings generally contain PC/ABS, but CRT TV housings often consist of HIPS. Meanwhile, flat panels are a mix of PC/ABS or HIPS.

Printers can have “up to four or five different plastics,” he noted, while the fronts and backs of TVs and monitors are often made with two different resin types. “E-plastics are a tough category due to the variety and complexity of the original recyclable that they are derived from,” Bolon said.

A typical e-scrap recycling operation in the U.S. will dismantle the electronic devices they receive and eventually send them through a shredding system, which produces a mix of plastics, metals, glass and other contaminants. Processors committed to recycling e-plastics will attempt to sort the plastics out through manual or automated separation systems, ideally producing homogenous streams for downstream buyers.

It’s an uphill climb, says Duane Beckett, the president of Brockport, N.Y.-based Sunnking Recycling.

“Recyclable plastics are kept separate into as clean of a stream as we can make it, much like any metal category that we separate into and sell,” Beckett said. “Plastics recyclers in general are very finicky with regards to the materials they accept.”

While Sunnking mostly attempts to recover the ABS plastics found in CRT and flat panel devices, Beckett noted not all electronics recycling operations have the necessary equipment or interest in handling the material. What doesn’t get recycled heads to landfill, “representing a significant cost over time,” Beckett noted.

Impediments to recovery

Beyond the sheer array of plastics found in consumer electronics, the use of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) has also been a historical barrier to recovery.

While many original equipment manufacturers have moved away from using BFRs in their products, older equipment, particularly TVs and computers, can still often contain the chemical mix. As the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes on its website, “Many flame retardant chemicals can persist in the environment, and studies have shown that some may be hazardous to people and animals.”

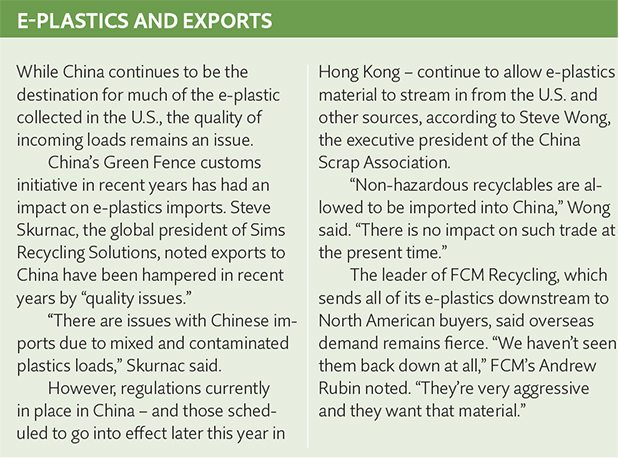

At present, there are no regulatory restrictions for incorporating recycled plastics with BFRs into new products in the U.S., but the domestic market remains limited. According to FCM’s Rubin, a “stigma” often surrounds BFR-containing recycled plastics, with most North American buyers interested in only non-BFR plastics at this point.

“Non-BFR plastics are hard to come by and [come] at a premium,” he said, noting that most North American recycling companies are forced to ship e-plastics abroad for further recycling.

The European Union restricted the use of BFRs in electronic products in 2003 under the Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive. The EPA, meanwhile, is continuing to study BFRs in accordance with the Toxic Substances Control Act for potential human health and environmental risks.

Another major impediment to e-plastics recovery in the U.S. comes down to simple economics. The value of e-plastics is often not worth the labor to attempt to separate the material.

“Mixed plastics [is] one of the lowest and least valuable of materials categories, and one of the most common materials streams derived from electrical and electronic equipment,” the NCER report from last year states. “The incredibly low value of this material underscores the challenges in assuming profitable recycling for all devices.”

According to the report, mixed plastics found in TVs, computers and printers had little to no recovery value. Electronic recycling companies largely echo that sentiment today.

Bolon from Novotec said the value of mixed e-plastics today ranges “from zero to a couple of cents” per pound.

Sean Magann, a vice president at Sims Recycling Solutions, said the company is able to move its e-plastics downstream despite its low value.

“The price is not what we’d like, but it’s our commitment to make sure the plastic is recycled,” Magann said.

Most e-plastics that are being recycled head to foreign markets, with China being the most popular destination for the material (see sidebar above). “They have the need for the plastic and the labor and technology to do more efficient separations than are generally possible in the U.S,” Bolon said.

“You can separate and regrind and develop domestic markets for recycled e-waste plastics,” he continued, “but it is a specialty and requires a lot of work and patience since the market changes all the time. And cheap virgin material can come in from China any time and eliminate a client’s orders quickly.”

Beckett from Sunnking said domestic outlets for e-plastics are hard to come by.

“We do not see any domestic outlets. The streams are too contaminated for any reuse opportunities in the U.S. without a significant investment in sorting equipment,” Beckett said.

Pushing e-plastics recovery forward

One company that has made such an investment, however, is FCM Recycling.

The Canadian electronics recycling company recently opened up a facility in Quebec that is dedicated to processing up to 15,000 metric tons of e-plastics a year. The company invested heavily in the operation – over $4 million in research and development and equipment.

“It was very clear to us as time evolved that plastics was becoming more and more representative in the waste stream,” said FCM’s Rubin.

The e-plastics site operated by FCM expects to process about 5,000 metric tons of material in 2017, all of which is being recycled in North America and used in a range of products, including construction shims, flower pots and trays and sheets used to manufacture various products.

In addition to utilizing a proprietary sorting process to successfully separate the various plastics, the plant utilizes grinders, air classification systems and metal detection systems.

“The markets are there. What it comes down to is making the investment in the equipment to bring it to a level where it’s usable,” Rubin explained. “You have to make the investment to separate the material, to grind the material down, to melt the material and re-pelletize it. If you get it to a pelletized form, there are plenty of markets for the material.”

Rubin also addressed the challenges associated with BFRs. “The material is perfectly safe and works just the same as any non-BFR material,” he noted. “You don’t want to put it in children’s toys and food, but apart from that, it has no effect on production and it doesn’t need to be handled specially.”

A related piece of the e-plastics recovery puzzle is generating enough large-scale and consistent demand to convince recovery firms to invest in equipment. Many have pointed to the need for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) in the electronics industry to close the loop on their products and reincorporate recovered e-plastics into new products.

One example of such activity can be seen at computer giant Dell, which works alongside manufacturer Wistron to bring recovered e-plastics into new products. Dell has operated a take-back program for years that allows the company to source and control its recycled feedstock directly. In 2014, Dell released its first computer featuring recycled e-plastic: the OptiPlex 3030 All-in-One desktop.

“The closed-loop process delivers an energy-efficient product made from recycled content that is nominally less expensive, with the potential to show greater cost savings as the program scales,” Dell notes on its website.

What’s needed to push recovery forward

What’s needed to push recovery forward

Steve Skurnac, the global president at Sims Recycling Solutions, said better resin separation and further OEM support could help catalyze domestic markets for e-plastics.

“Better resin separation will drive higher prices and manufacturers trying to close the loop may sponsor plastic recycling and remanufacturing initiatives with recyclers,” Skurnac said.

Bolon of Novotec noted that obtaining enough supply is crucial to developing markets further downstream, especially when it comes to manufacturers.

“For any plastic, no matter how clean it is, if you don’t have enough volume, there is no market,” Bolon said. “A manufacturer has to be able to rely on a constant supply of the same exact product in order to set up a line or product.”

Sunnking’s Beckett also pointed out that recycling companies have to be willing to make the investment to separate e-plastics by resin type and then store material in order to produce a marketable commodity.

“Unless a processor has a large facility or a baler, loose plastics take a large amount of floor or gaylord space,” said Beckett. “This is also costly.”

But as complex as the e-plastics stream may be, electronics processors are beginning to see it as an important commodity stream in the years ahead and one that will, at some point or another, drive investment.

“It’s only a matter of time that new and novel solutions pop up to treat this material here in North America,” FCM’s Rubin said. “Everyone knows that.”

Bobby Elliott is editor at large for Plastics Recycling Update. He can be contacted at [email protected].