Note: This op-ed originally appeared on Adam Minter’s blog, Shanghai Scrap

Below, a pic I took a few weeks ago in Hauqiangbei, a commercial district in Shenzhen, China. It’s the beating heart of the global electronics industry, the world’s most important marketplace for everything electronic – phones, computers, playable piano keyboards that roll up like a crepe.

But what makes Huaqiangbei unique is that “everything,” in this case, means parts. If you’re in need of a processor, cable, board, capacitor, screen, screw, or backing plate manufactured in the last 20 years, someone in Huaqiangbei has it – in bulk. Such as these used chips that I photographed at Huaqiangbei’s SEG Plaza in May:

The owner of the stall said that the source of the chips was “PCs in internet cafes.” In China, at least, that’s a lot of potential PCs. In 2015, China had 146,000 internet cafes. When those cafe PCs aren’t wanted, anymore, somebody goes through the trouble of breaking them down into parts for sale to a willing market, which in China oftentimes means Huaqiangbei. It’s not just for hobbyists, either. For years, used Chinese parts have found their way into finished products that range from toys to U.S. Navy cargo planes.

Does everyone who buys those used parts know they’re used? Nope. Sometimes they’re sold as new, and sometimes they’re sold to people who put them in parts that are sold as parts. Along the way, the provenance goes missing. If it goes missing by design – that is, if someone sells an old product as new – the action is oftentimes labeled counterfeiting (I’ll get to that in a moment). More charitably, I suppose, we could also call it “green fraud.” After all, what’s better for the environment than reusing a product?

Anyway, a recently as 10 years ago, most of the used equipment in Huaqiangbei was imported from developed countries such as the United States, torn apart in e-waste processing zones, and then shipped to a Huaqiangbei stall owner. In fact, business owners in China’s most notorious e-waste “dumping” zones oftentimes maintain retail arms in the SEG Plaza and other markets in Huaqiangbei.

But around 2008 things started changing as China became the world’s largest consumer of consumer electronics, including PCs and mobile phones. Obviously, you can’t buy electronics without eventually wanting to throw them away. And soon, China will also be the world’s largest generator of e-scrap; currently, according to the United Nations, it’s second to the United States.

In 2012, a Senate Armed Services Committee report on “counterfeit” electronics – that is, used items sold as new – purchased by the military claimed that China was the source. That should not have been news to anyone. China’s used-electronics-parts industry complements and enhances the supply chains for China’s new electronics, and it’s been doing so for years. As China tosses out more old electronics, that relationship should further tighten.

I bring this up for a very specific reason. Late last month U.S. Rep. Paul Cook of California introduced the Secure E-Waste and Export Act. The legislation’s goal is to prevent counterfeit parts from making their way into U.S. military hardware. To pull this off, the bill will ban the export of all used, non-working electronics from the United States.

But if China is already one of the world’s biggest generators of e-scrap, it’s difficult to see how this will make any difference. China will keep generating parts and – so long as the U.S. military contracts with companies that manufacture in China – some of those “counterfeit” Chinese parts will make their way into military orders.

So it’s a dumb and unnecessary bill. But that’s not the worst of it. Rep. Cook’s bill is also an environmentally destructive piece of legislation.

Here’s why.

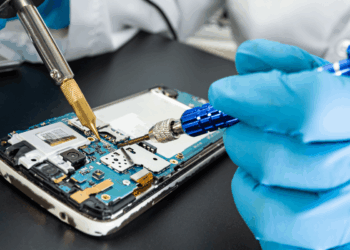

Below, an image of a badly damaged iPhone 6. It’s the first photo in a 67-image slideshow at China’s Netease web portal (scroll past the iPhone 7 slideshow to find it). The title caught my eye: “How a scrapped iPhone is refurbished: ¥200 [$30] changes into ¥3000 [$450].”

Under the proposed definitions in Rep. Cook’s legislation, that phone – clearly a piece of junk, right? – would be prohibited for export. The presumption is that that such a phone could never be made to work again; it can only be parted out and those parts counterfeited.

It’s worth clicking through the entire slideshow to see what happens. But let me offer up a couple of images. First, an image of the iPhone 6’s shattered logic board. Unrepairable, right?

Wrong! In image 51, below, you see the final stages of a process whereby that shattered logic board is made whole again using parts from another logic board. This is the kind of thing no Apple Genius Bar would ever attempt. They’d just tell you to get a new phone and promise to recycle the one you’ve broken.

This isn’t some hobbyist doing the operation. It’s being done in volume at a commercial location. In image 58, you can see piles of spare screens and cases to replace the damaged ones that this repair/refurb shop (it’s never identified) repairs in volumes. There’s nothing rare about this, either. Repair and refurbishment at the board level has been common in China for years. In the early 2000s, I regularly saw it in the used PC malls that were common features in Chinese cities. And today you can find board-level repair and customization in electronics shops all over China and other parts of Asia. The phones are oftentimes imported – such as the broken Malaysian phones I saw being repaired in a Mumbai shop back in November.

And finally, below, a newly refurbished iPhone, ready to be sold for hundreds of dollars.

If that newly refurbished iPhone had been broken in the U.S., and subject to export controls, it wouldn’t have been repaired. Instead, it’d either be in a desk drawer somewhere, or a recycling company would have sent it through a shredder, extracted the various commodities, and sent them on the way to being new products. The latter case sounds great, except that it uses far more energy, and requires many more new raw materials than a phone that has its life extended by a repair tech. To my mind, the environmental case for repair has never been stronger.

I want to conclude on two points. First, a note to my friends in the U.S. electronics recycling industry. The next time an Asian or African recycling recycler outbids you for non-working equipment, I hope you’ll avoid suggesting that they can do so because they aren’t subject to U.S.-style environmental, health and safety regulations. That’s true so far as it goes. But what’s also the case is that they have access to repair, refurbishment and parts markets that make such purchases possible (can you turn a $30 piece of junk into a refurbished iPhone worth $400?). Not only that, they have a far better chance of extending the life of a device than a U.S. recycling company, and that repair move offers a much greater environmental benefit than what can be attained by recycling a device into new materials.

Second point. If the U.S. recycling industry (and Rep. Cook) is really keen to keep used U.S. electronics in the United States, it should turn its attention to supporting “Right to Repair” bills popping up in various U.S. states.

The idea is simple. Repair techs should have the right to the same parts and repair documentation as the electronics companies that make devices. Automobile manufacturers already do this (more or less); there’s no reason it shouldn’t be demanded of Apple, as well.

Yet for reasons all of their own, America’s consumer electronics companies are fighting tooth and nail to keep consumers from having these rights, those parts and that documentation. It’s not the only reason that used U.S. devices go abroad. But it’s among them, and it’s time to fix it.

Adam Minter is an Asia-based columnist at Bloomberg View. His first book, Junkyard Planet, was published in 2013.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Resource Recycling, Inc. If you have a subject you wish to cover in a future Op-Ed, please send a short proposal to [email protected] for consideration.