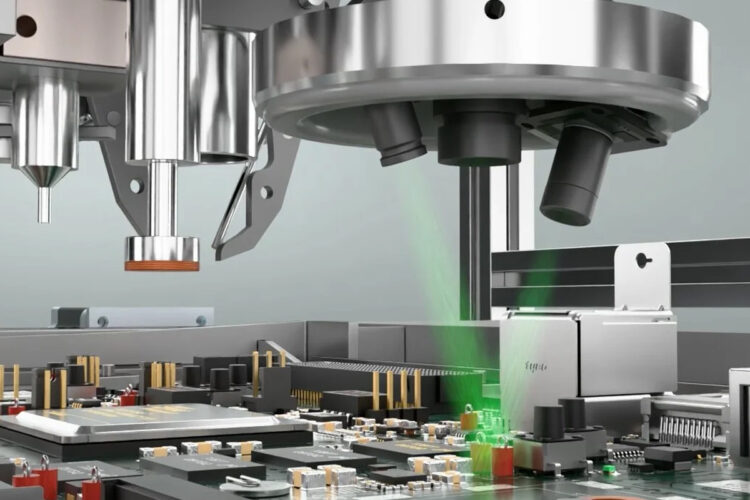

A Northern California startup is developing an autonomous robot that recovers valuable electronic components intact, a process it describes as “surgical harvesting” and an alternative to standard shredding.

San Francisco-based Tuurny is pitching the approach as a response to persistent chip shortages and the rising volume of discarded electronics. Its goal is to supply a domestic stream of reusable parts by pulling high-value components from circuit boards without damaging them.

The platform uses computer vision to inspect each board, identify chips, capacitors, connectors and other parts, then remove them with precision robotics. The system is designed to allow each component to remain undamaged and to create documentation that follows the part once removed from the original hardware. In contrast, device shredding still dominates in the US and produces mixed scrap rather than individual, traceable electronics.

Sina Ghashghaei, CEO of Tuurny, argued that traditional destruction methods erase value. “Shredding electronics is like putting a classic Ferrari into a car crusher just to sell the metal as scrap,” he said. He added that the company wants to avoid destroying what he described as “a priceless engine and transmission” that could still be put to use. Tuurny aims to remove high-value components carefully, confirm their condition for potential reuse and return them to service in new hardware.

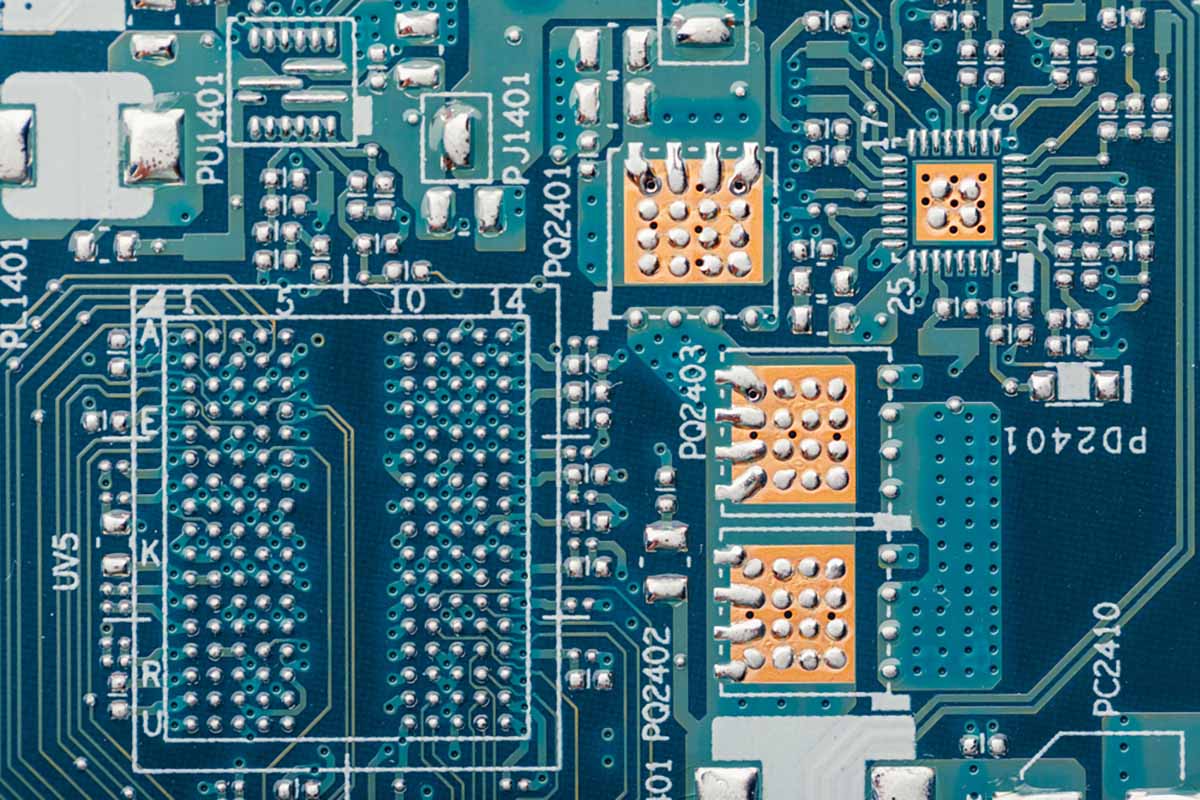

The timing, Ghashghaei noted, reflects growing demand for parts that have gone out of production. The company’s documentation process creates a digital certificate for every recovered component and links it to the hardware it came from.

He said many long-life defense platforms rely on sunset or legacy electronics, and that sourcing those parts can be a logistical and security challenge with a risk of counterfeit infiltration. Tuurny intends to address that concern by proving where each component originated and by supporting compliance with the Pentagon’s DFARS 252.246-7007 requirement for a counterfeit electronic part detection and avoidance system.

Tuurny has secured a NASA grant to work with Texas A&M University on the development of the platform’s computer vision model. It has also been accepted into the NVIDIA Inception program, which supports startups that use AI tools in technical and industrial settings.

The company describes its work as a high-margin recovery model built to preserve value that is now lost in most e-scrap operations. The robot is being designed to handle a range of devices and to generate a consistent data record for every recovered part. Tuurny maintains that the value comes from supplying a certified component with a known history rather than a commodity mixture of shredded metals and plastic.

The first production-intent system is nearing completion as the startup prepares to expand its engineering team and move toward commercialization. The next step is raising its seed round to finalize development and begin paid pilot programs with customers who need traceable legacy components.

Tuurny places its work within ongoing concerns about supply chain reliability. Although chip availability has improved since the worst shortages earlier in the decade, demand for legacy electronics remains high in aerospace, defense, medical systems and other fields where equipment remains in service for many years. The aim is to create a recovery channel that returns documented components to manufacturers and service providers that depend on them.

The platform is still in the prototyping stage, but early testing supports the belief that value can be recovered without destroying the hardware. Tuurny’s long-term plan is to scale the system into an operation that can process discarded electronics in a controlled environment and return tested parts to circulation.