As industry seeks to grow acceptance of molecular recycling technologies, how we define these technologies is becoming increasingly important.

For decades, mechanical recycling was the only tool in our materials management toolkit to keep plastics in circularity. Today, the range of tools is growing rapidly as different molecular recycling technologies reach a commercial scale. By clearly defining these technologies and categorizing their respective outputs, we can more accurately paint the complete picture of the current state of recycling.

One example of how the definition has yet to be clearly defined is in the name itself. Over the last 10 years, the terms “chemical,” “advanced” and “molecular” have been used interchangeably. From these three options, “molecular recycling” is the most accurate term for technologies that impact the molecular structure of the plastic.

This definition would also mean purification technologies are better classified under mechanical recycling. The term “advanced recycling” does not work because it gives the connotation that mechanical recycling is less advanced in some way, which is not true. There are some amazing advancements happening in mechanical recycling using robotics and AI. Finally, the term “chemical recycling” is too broad because chemical principles are being applied in any type of recycling.

Over the past year, the question “Does molecular recycling count as recycling?” has come up more and more at various conferences and trade events. Why is this question important? Because under today’s recycling paradigm, understanding what processes are classified as recycling drives what is defined as recycled content. This has growing importance as brands and governments strive to reach ambitious recycled-content goals.

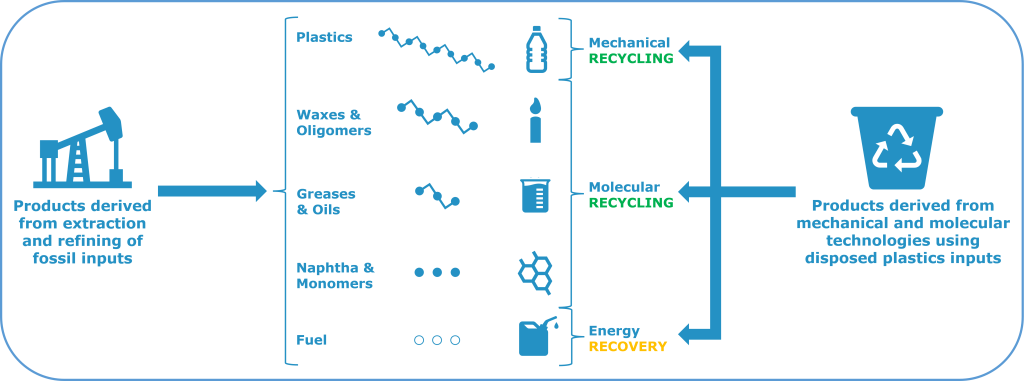

Categorizing by outputs, not processes

Historically, we have categorized molecular recycling based on the different process or technology types. But is pyrolysis truly recycling? How about gasification? Answering these questions is not straightforward, because these technologies can be employed in different ways to produce a range of output products.

Some of these outputs, depending on downstream treatment, may or may not qualify as recycled materials. Outputs used for energy production are typically characterized as “recovered” rather than “recycled.”

On the other hand, outputs that are used as chemical feedstocks – ones that can be transformed into building blocks for a wide range of products – by all accepted definitions qualify as recycled content.

If we use the final output of the process – rather than the process itself – to define what qualifies as recycling, only then can we accurately capture what falls into the true definition of recycling: converting waste into a reusable material.

A prime example of where this becomes complicated is pyrolysis – perhaps the best known molecular recycling process – which produces fuels and chemical feedstocks. So is pyrolysis truly recycling?

Because the classification of the resulting products as recycled is of most consequence, perhaps we should not be answering the question “Does molecular recycling count as recycling?” Maybe the better question is “Which products derived from molecular recycling technologies qualify as recycled content?”

Ultimately, no matter the process, there are truly only a handful of outputs that can be achieved when plastic is utilized as an input:

- Polymers (plastic)

- Oligomers (waxes or other low-molecular-weight plastics)

- Building blocks (monomers, naphtha)

- Other resources (solvents, oils, char, graphene, carbon, etc.)

- Fuels

Therefore, as an industry, we need to study each of these outputs and determine whether to classify them as “recycled” or “recovered.”

If we use the final output of the process – rather than the process itself – to define what qualifies as recycling, only then can we accurately capture what falls into the true definition of recycling: converting waste into a reusable material.

(Article continues below image. Click image to view full size in a new browser tab.)

In its simplest form, recycling is about keeping a product, material or resource in constant use and not allowing it to be discarded into our environment – either through landfill or emissions – or consumed in a way that it can never be used again (for example, as energy).

This basic definition should and can be applied to all commodity materials we use in our everyday life, including paper, plastic, metal and glass. Where things become a bit complex is in the understanding that the action of recycling and circularity does not begin when we are ready to discard a product. It starts right from its inception.

The way a product is designed and the choice of materials used have a big impact not only on whether something can be recycled but also on whether it can produce a net positive or negative environmental impact.

When we are ready to discard a product, the need to consider how we recover the valuable materials from that product and return those materials to the manufacturing system is critical.

To deliver on this point, we need to consider as many recycling pathways as possible, following a reuse hierarchy:

- Reuse of the product

- Then reuse of the material

- And finally, reuse of the resources (for example, plastic to hydrocarbon molecules, glass to silica, or paper to cellulose)

As we look to meaningfully shift from a linear economy to a circular one, we will have to rethink how we define recycling. And if the goal is to keep materials in play, then perhaps we define the success of that by the resulting material outputs rather than the processes that create them.

So does molecular recycling count as recycling? I’d propose we don’t get hung up on answering that question. Instead, let’s look at the products these processes create and ask: “Does this create products that can be returned to the manufacturing process?”

Shifting where we measure recycling

Defining recycling by outputs will then also require a shift in where we measure recycling in the system. If a technology like pyrolysis is not in its entirety a recycling solution because it generates fuels and chemical products for manufacturing, then we must start accounting for recycling at the point products come out of the system, not at the point that materials go into the system. This may be a very different approach than how we calculate recycling rates today.

The questions posed here are just a few examples of how we are being challenged to rethink many things as we embrace big shifts in materials management. This means being open to rethinking our frameworks – down to definitions – to accommodate innovations that will help us reach circularity goals.

The economy we live in has a major waste problem, not just with regard to plastic but all materials. If we are to make fast and impactful strides in changing that, we need a coherent and connected plan that involves all stakeholders, including government, industry and consumers.

We need to leverage all suitable solutions as appropriate, including circular mandates, new product design, better infrastructure for waste collection and sortation, and a hierarchy to the process of recycling that starts locally to recapture the product and then moves to different industrial processes.

A clear and generally accepted definition of “molecular recycling” allows us to leverage those current and future technologies to recapture resources before they enter our environment and reduce dependency on mining of virgin/fossil resources.

Domenic Di Mondo is president of GreenMantra Technologies, an Ontario, Canada-based company that recycles post-consumer plastics into specialty polymers for multiple different applications.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Resource Recycling, Inc. If you have a subject you wish to cover in an op-ed, please send a short proposal to [email protected] for consideration.

A version of this story appeared in Plastics Recycling Update on January 5.