This story originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

New Mexico’s vast expanses and natural beauty long ago helped inspire the state’s nickname: Land of Enchantment. Yet those same open spaces served as a barrier to rural communities that wanted and needed to recycle.

The hub-and-spoke recycling efforts launched by the New Mexico Recycling Coalition (NMRC) from 2008 to 2012 helped to provide access to recycling in these communities. Five years later, many rural recycling hubs have made programmatic updates or changes, enabling them to more efficiently collect items for their partner spokes and capitalize on economies of scale. The New Mexico model – and its recent adaptations to current recycling realities – can help inform the development of collection and processing infrastructure in other rural environments.

Birth of the system

In 2008 the NMRC began the process of addressing recycling in rural areas by creating an inventory of existing facilities for both municipal solid waste and recyclables. The effort clearly identified access to facilities as a leading barrier. With this tool in hand, NMRC sought funds to develop the required infrastructure and in 2010 received a $2.8 million dollar grant from the U.S. Department of Energy’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant program.

This once-in-a-lifetime funding opportunity was complemented by money from the state’s Recycling and Illegal Dumping (RAID) grant initiative as well as a second pool of roughly $500,000 in ARRA funds awarded to the New Mexico Environment Department.

The funding allowed New Mexico to develop a hub-and-spoke recycling system. This strategy relies on regional recycling processing centers, generally located within larger communities, that serve as “hubs” and encourages smaller communities or “spokes” to deliver their recyclables to these centers. The approach suits the rural nature of New Mexico well and provides the most efficient means of gathering and processing recyclables from both a capital and operational cost perspective.

The grant funding helped create six new regional recycling processing hubs, improved two existing recycling hubs and added more than 40 new drop-off locations – the spokes – in rural and underserved areas.

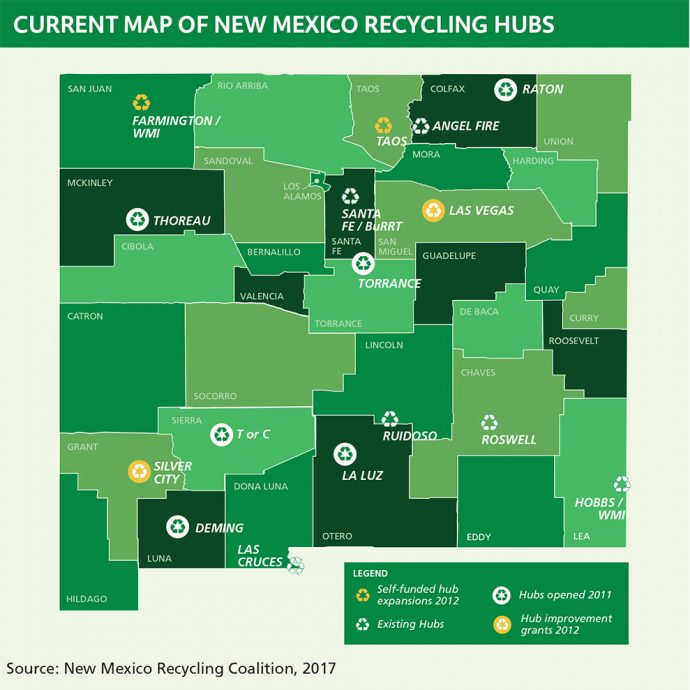

The map shows recycling hubs in New Mexico as of early 2017. All eight of the hubs that opened in 2011 and 2012 through the support of the ARRA funding are still serving as regional recycling hubs today with outlying spokes still feeding them. In general, spokes are no more than 50 miles away from the hubs. Oftentimes, the spokes are within the same county as the hub city and require partnerships between counties and cities.

Initial results of the New Mexico effort included creating 38 direct jobs and 52 indirect jobs. The model also increased recycling access for traditional household recyclables by 113 percent throughout the state from 2007 to 2013, with 115 new locations serving a total population of over 440,000 residents gaining access during that period. Access here is defined as having a recycling drop-off location within 30 miles of the generator, and traditional household recycling is defined as the opportunity to recycle cardboard, paper, aluminum, tin and Nos. 1 and 2 plastic bottles.

Grant funding was also used to create the Rural Recycling Resources marketing cooperative (R3 Coop), The R3 Coop took the administrative burden away from small government entities to market recyclables and ensured a fair price for materials by acting as a material broker and by working closely with both hubs and end markets to coordinate efficient transportation.

Shifts in the market

Since the launch of the hub-and-spoke program five years ago, New Mexico has experienced significant changes to the overall recycling landscape: some changes were universal and affected programs nationwide, but others were specific to the state.

First and foremost, New Mexico recyclers were challenged by the degradation of market prices of recyclables that began in 2013 and stung programs across North America. Programs that had built their rate structures dependent on the higher rates from the sale of recyclables struggled to continue to keep their operations in the black.

In New Mexico, rural solid waste programs’ financial woes from low market prices were worsened by the reduction in state revenue from lower oil and gas prices. Between 15 and 26 percent of New Mexico’s total general fund depends on revenue from oil and gas operations. From October of 2015 through 2016, more than a third of New Mexico’s oil rigs shut down. This translated into attempted cash grabs by the state legislature of monies from the RAID fund and very little funding for capital outlay projects.

Another big development in the state’s recycling ecosystem was the opening of the state’s first large-scale single-stream materials recovery facility (MRF). In 2012, Friedman Recycling Company won a 12-year contract to provide New Mexico’s largest city, Albuquerque, with a $20 million dollar plant that now employs over 70 individuals and includes state-of-the-art sorting systems that make single-stream recycling a viable option in New Mexico. The facility, which came on-line in 2013, has a capacity of 14,000 tons per month and serves as a new potential market for rural programs.

Also important was the successful phase-out of the R3 Coop in 2015. The initial purpose of the marketing cooperative was to assist communities in marketing their material, but in late 2014 it became apparent the service was no longer necessary: New markets had become available, and member hubs were producing enough material to ship their own loads in a timely manner. It seemed wasteful for NMRC to take the 7.5 percent R3 Coop administrative fee away from communities, so the R3 Coop proudly put itself out of business in early 2015.

Finally, in 2015, the New Mexico Environment Department released an updated Solid Waste Management Plan that utilized a goal-oriented format to help communities more easily identify steps they can take to meet the plan’s intent. New objectives for the 2015 plan include prioritizing RAID funding for three specific kinds of communities: those that make use of the hub-and-spoke model, those that are currently without access to recycling, and those that focus on full-cost accounting to ensure program sustainability even during periods of low markets for recyclables.

Tonnage growth and hub resiliency

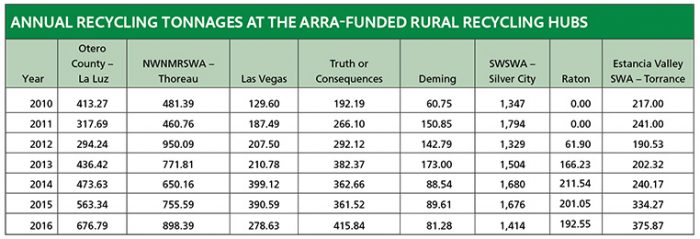

The table on this page shows the total tons recycled at each of the eight ARRA-funded hubs over the past seven years. Overall, tonnages increased in recent years with a few exceptions.

The decline in tons in 2016 in Silver City is attributed to the city discontinuing its glass recycling operations, collection equipment issues during the year and the lack of a shipment of recovered electronics (e-scrap is only sent to market from Silver City every 14-16 months). In addition, the City of Deming removed its green waste and scrap tire diversion programs in 2014, causing the tons of material recycled to be lower. However, the quality of the city’s traditional household recyclable materials has improved in recent years thanks to public education efforts. Similarly, the City of Las Vegas experienced a reduction in tons recycled in 2016 because of equipment issues with a yard waste grinder – these problems were resolved later in the year.

How has the New Mexico system been able to consistently boost tonnages, even amid market challenges?

One step has been the production of high-quality material and development of strong relationships with end markets. The high-quality bales were often the result of source-separated collections (only two hubs manage single-stream material) and many of the relationships with end markets were the result of the R3 Coop. The eight ARRA-funded rural recycling hubs further weathered low markets by establishing solid waste rates that helped pay for recycling operations. Decisions about rates and other key components factored in cost avoidance for each ton recycled in terms of avoided transportation and landfill tipping fees.

Continued outside funding efforts have also helped. The RAID grants are funded through a 50-cent fee on annual vehicle registrations and generate approximately $800,000 per year, of which two-thirds of the money goes toward scrap tire management projects and one-third goes toward recycling and illegal dumping abatement. The new funding priorities outlined as part of the 2015 Solid Waste Management plan facilitated a total of approximately $633,469 in awards to 23 rural communities between 2015 and 2017, allowing them to further expand hub-and-spoke recycling operations.

Furthermore, as programs matured, recycling hubs began looking for ways to expand their operations and collection locations. Many recycling centers increased their number of spoke collection points by providing service, and in some cases the physical containers, to additional locations.

For instance, ARRA funding for Otero County’s La Luz recycling center initially created 11 new drop-off sites for recycling in the county. Increased recycling cut out 17,466 landfill transportation miles in one year alone and saved associated costs. With improved capacity to process recyclables, the county was able to write a successful grant to the New Mexico Environment Department for RAID funding in 2013 to receive five containers that are now being used to collect cardboard from businesses, further increasing tons of material recycled.

Another example of smart work on the ground can be seen at the hub in the community of Thoreau. This site is operated by the Northwest New Mexico Regional Solid Waste Authority (NWNMRSWA), which services Cibola and McKinley Counties and is fed by over 20 spoke locations, all of which are staffed to control contamination issues. Income from the NWNMRSWA landfill helps to pay for recycling operations, a fact that allowed the Thoreau hub to continue its operations during low markets and helped to fund collection containers for spokes. Recently, the authority received a 2016 RAID grant to expand its collection services and provide containers for the University of New Mexico’s Gallup campus.

The NWNMRSWA is managed by self-proclaimed “landfill guys” who are responding to the learning curve of recycling with resourcefulness and tenacity, and their commitment to provide recycling to residents has led to program success.

Expanded collections have also been established at the Raton and Las Vegas recycling hubs with Raton offering four new recycling collection spokes for cardboard and Las Vegas receiving a RAID grant in 2014 to purchase cardboard collection containers for business recycling. Las Vegas now has an active commercial cardboard route with 142 customers.

Better options at the curb

Increased efficiency has also enabled programs to provide residents with higher levels of service.

As an example, over the past five years the Town of Silver City has ushered in a fully automated curbside, cart-based residential and business recycling system. Through the South West Solid Waste Authority (SWSWA), the municipality was previously sending non-baled recyclables to market at a cost of $18 per ton. But with ARRA funding for a hub “improvement” grant in 2012, SWSWA was able to bale the single-stream material and sort out valuable cardboard. Now, instead of seeing recycling as a cost, Silver City receives an average of $15 per ton for the baled single-stream material and has dramatically increased transportation efficiency.

With these improved operations the community was able to focus on automated, cart-based curbside recycling programs. In February of 2017, Silver City replaced its 25-gallon tubs used in a manual curbside collection program with 65-gallon carts. It also upgraded commercial recycling operations by providing local businesses with 450-gallon recycling carts.

The evolving programs have been able to put better focus on specific materials. Otero County’s list of expanded services includes taking over glass recycling operations from the nearby Holloman Air Force Base. As of 2015, glass is accepted at the county’s hub in La Luz, and it is crushed and hauled to Colorado to be recycled.

Programmatic updates within rural recycling in New Mexico wouldn’t be complete without discussing single-stream collections. The switch to single stream wasn’t readily available to most rural communities in New Mexico prior to the opening of the Friedman MRF in Albuquerque in 2013.

Estancia Valley Solid Waste Authority (EVSWA) operates the landfill and recycling hub in Moriarty, New Mexico, a rural ranching community that is only 40 miles east of Albuquerque. When the Friedman facility created a nearby market for single-stream material, EVSWA evaluated its operational costs and in 2014 transformed operations to modified single stream. The change allowed EVSWA to increase program participation without increasing labor expenses. As the table shows, EVSWA’s recycling tons increased by nearly 40 percent from 2014 to 2015.

Later this spring Las Vegas will be launching a modified single-stream curbside pilot program for 175 households, and that material will be transported to the Friedman MRF. The Las Vegas recycling hub will continue to service its source-separated spokes, but it will begin baling curbside single stream (minus cardboard, which it will continue to collect separately).

A proven infrastructure

A key to hub-and-spoke rural recycling success in New Mexico has been solid waste managers’ willingness to adapt to new realities and situations. As the landscape changes in New Mexico, it is important for programs to continue to combat contamination, better understand actual operating expenses, develop new partnerships and consider programmatic updates.

Having a continued source of funding, such as the RAID grants, facilitates the ability for programs to update their infrastructure according to their community’s unique needs. Per state statute, the RAID funds are competitive and are administered by the RAID Alliance, a team of 12 highly knowledgeable stakeholders working in or with the recycling field in New Mexico. This well-informed group understands the recycling scene within the state and draws upon that knowledge to award funding.

There is not a one-size-fits-all solution to rural recycling. Hub-and-spoke worked in New Mexico because it’s a large, mostly rural state that had a need to increase access to recycling, and it received a boost in funding.

However, hub-and-spoke recycling does not need to be a state-wide endeavor – it can operate just as effectively on a smaller, more regional level. It is a system that allows communities to pool their resources and not have adjacent recycling centers competing for the same, limited volume of material.

In New Mexico’s system, recycling collection and processing programs are well established and communities have proven their ability to adapt to new conditions as they arise. This infrastructure will continue to divert materials from the landfill, saving energy, creating jobs and reducing transportation miles.

Sarah Pierpont is the executive director of the New Mexico Recycling Coalition. She can be contacted at [email protected].