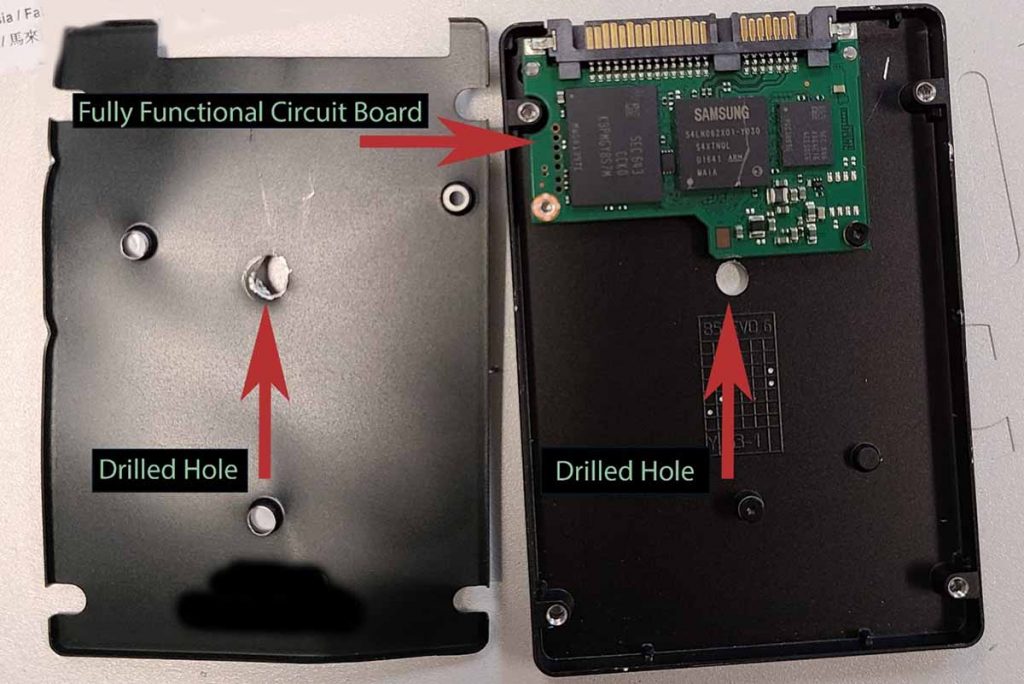

A sample of a drilled drive with the internal circuit board still intact. | Courtesy of CyberCrunch

Solid-state drives (SSDs) have revolutionized storage but pose a significant security challenge to businesses and ITAD providers.

Consider this brief case study: A little while back, a large corporation with tens of thousands of employees and billions of dollars in revenue sent CyberCrunch some “already destroyed” hard drives. As I walked by the gaylord, I noticed that the company had drilled through some 2.5-inch SSDs. Being familiar with these drives, I knew the drill hadn’t even touched the internal circuit board. All of the damage was cosmetic (see photo of drilled drive).

I plugged one into our hard-drive verification dock and found that the drive was not encrypted and that confidential company information was accessible. I was shocked. Clearly, this company did not have an appropriate destruction policy. They failed both the physical-destruction process and the verification process.

This experience helps illustrate why SSDs – non-mechanical storage systems that have been integrated into nearly all IT devices – pose particular challenges. This article will dive deeper into those challenges.

Wipe or physically destroy?

The fundamentals of compliant data destruction include the actual data destruction, verification of the data destruction and, finally, documentation of these two processes. Each of these steps is vital to complying with all major data-compliance requirements.

Destruction of SSDs can be categorized into two categories: sanitization/wiping and physical destruction. Each has its own unique challenges.

SSD wiping is one of the biggest challenges facing data-destruction experts. With traditional magnetic drives, one generally has block-level access to devices. This allows you to write to each block and also verify that the block was successfully written to. This is no longer possible with SSDs. Data on SSDs is accessed through a controller. You are at the mercy of this controller when wiping an SSD. This poses a challenge when attempting to wipe and verify the effectiveness of a wipe.

Many people ask me how many passes we use for wiping a hard drive. When I hear this question, I know this particular person is not well versed in data erasure. My response to this question is always to ask, “What type of device are you referring to?”

Many people falsely believe that three or seven passes will destroy the data on a SSD. However, SSDs cannot be wiped like a standard hard drive. The number of passes is irrelevant, and if you are relying on multiple passes, then you most likely are not using the correct software for wiping your SSD.

Many manufacturers have integrated wiping processes into their controllers. The most common process is ATA-Secure Erase. This tool will work with most modern Serial Advanced Technology Attachment (SATA) SSD devices. Theoretically, these commands should completely zero a device. However, a study conducted by Michael Wei and other researchers at the University of California, San Diego found that many manufacturers did not implement these commands correctly and that data were easily recovered.

This means that ATA-Secure Erase should be just one part of the data wiping process for SATA SSDs. ATA-Secure Erase can be found on the popular software package Parted-Magic and is integrated into most modern reputable wiping software programs. ATA-Secure Erase can be finicky. It generally cannot be run using USB connections, and some BIOSes can prove to be problematic when dealing with SSD wiping. Using a dedicated wiping machine can help to alleviate some of these problems.

Although the ATA-Secure Erase command will unlock the device upon completion, one cannot be sure the data was wiped simply because raw data cannot be accessed. Further action is necessary to supplement this wipe.

Encryption is the second step of the process. However, it should not be relied upon as a standalone wiping methodology either. Encryption is only as good as the algorithm used. Many hard-drive manufacturers are offering self-encrypting drives (SEDs). Theoretically, one can wipe the key, and all of the data will be inaccessible. But research has shown the shortcomings of cryptographic erasure.

So how are you supposed to wipe an SSD successfully? I recommend a multi-pronged sanitization and verification process. Don’t just rely on one process but use multiple processes: both cryptographic erasure along with ATA-Secure Erase. In addition, be sure to verify that your wipe has worked. Many major hard-drive vendors provide product-specific tools to wipe their devices. But remember, many tools do not include verification and documentation. These must be done separately.

Takeaways: SSD wiping is a complex process. Specialized software and hardware may be required. Do not use older overwrite software because it is ineffective when used on solid-state media. Don’t forget to verify every erasure and consider third-party audits of your wiping methodology.

(SAS-based solid-state media wiping is not covered in this article. These devices are generally used in an enterprise setting, and each manufacturer has its own tools for this. But the same fundamentals apply: destroy, verify and document.)

Now let’s move to physical destruction.

Physical destruction was easy with traditional magnetic hard drives, because they were large and had giant platters. Most shredders would shred at three-quarters of an inch, or about 19 millimeters, which was generally considered satisfactory.

SSDs can be extremely small, however. You can buy a 1 TB microSD card that is 11 millimeters wide and 1 millimeter thick. That being said, most SSD hard drives aren’t quite that small. The most common sizes we see are 2.5-inch standard drives, mSATA and M.2. Traditional hard-drive shredders are not sufficient for these. Pulverization is the preferred method. Some presses with teeth will work on the 2.5-inch devices but may not be sufficient for the smaller mSATA and M.2 devices.

The first part of physical destruction includes locating the solid-state media. Proper training is imperative. SSDs can be attached to motherboards or inside PCI cards and other enclosures. These can be very difficult to find with an untrained eye. Many new devices can have both SSDs and traditional hard drives.

Takeaways for physical destruction of SSDs: Be sure your shred size is small enough to ensure destruction of the flash media chip. A 10 millimeter shredder may be fine for 2.5-inch devices, but you may need to be at 2 millimeters for smaller devices. These methods should be combined with smelting to ensure a complete destruction process.

Some advice for clients and ITAD providers

I recommend businesses consider implementing company-wide policies requiring encryption of all data-containing devices. This provides a business with its first line of defense when devices are retired. When devices reach their end-of-life, a business should always utilize a NAID-certified provider that is approved for SSD destruction. Currently, only a handful of companies are NAID-AAA certified for SSD destruction and wiping, like CyberCrunch.

A word to fellow ITAD providers: Make sure you know what you don’t know, and always double and triple check. Ensure management has adequate training about data-destruction policies. Consider hiring a data-erasure consultant, who may be able to help you improve your SSD-destruction policies. Use third-party random audits to verify your destruction processes.

Serdar Bankaci is a self-described nerd and entrepreneur. He started his career in the data business but found his calling in the e-waste industry. Bankaci is the founder and president of CyberCrunch, the industry leader in data destruction and reuse. Under Bankaci’s leadership, in less than a decade, CyberCrunch has gone from a three-person operation to a global ITAD company. He also serves as a board member of Westmoreland Cleanways and Recycling in Greensburg, Pa.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.