This article originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The passage that follows is an excerpt from “Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale” by Adam Minter (available now from Bloomsbury). At this stage in the book, Minter is traveling in Ghana with two companions: Robin Ingenthron, owner of U.S. e-scrap firm Good Point Recycling, and Oluu Orga, who spent years scrapping in and outside of Agbogbloshie and today manages a store that sells secondhand IT in northern Ghana.

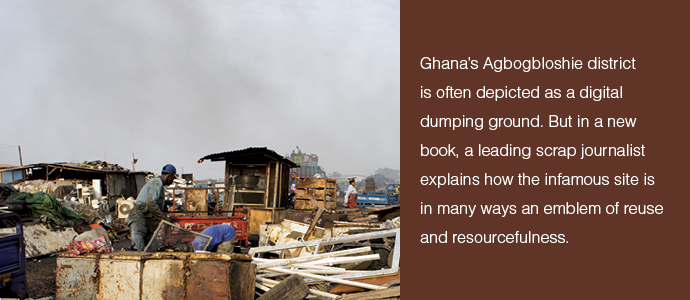

It’s early evening, and the shadows are growing long as Oluu, Robin, and I step out of a taxi and into a dusty parking lot across the street from a place that The Guardian labeled “the world’s largest digital dump,” CBC called “the world’s largest e-waste dump,” Al Jazeera called “the world’s biggest e-waste dump,” and PBS’s “Frontline” declared the final destination for “hundreds of millions of tons” of e-waste annually (a volume that, if true – and it’s not – exceeds the volume of waste computers, phones and televisions generated every year on a global basis by a factor of five, at least). Other news organizations, environmental organizations, and government bureaucracies have repeated these same statistics, turning them to flawed conventional wisdom.

More than any other place on Earth, this place, Agbogbloshie, has defined the Western image of a globalized trade in secondhand goods. If, when you read the words “used computers Africa,” you conjure an image of young black men tending to smoking clouds of electronics, you’re probably thinking of Agbogbloshie. If the words “electronics dumping” generate feelings of indignation based on a documentary you saw or story you read years ago, odds are that story was about or at least included mention of Agbogbloshie.

But the funny thing about a place that Time once called one of the 10 most polluted places on Earth is that it doesn’t look or feel that way from a parking lot across from the street. Instead, I see the famous yam market’s roadside wooden stalls stocked with yams and red onions, and diesel trucks loaded down with even more yams slowly navigating choking traffic. After the yams, the most noticeable things about Agbogbloshie – at least from across the street – are a bus station that conveys Ghanaians all over West Africa, a Pepsi bottling plant, a meat market, several banks, dozens of used computer shops, used-car dealerships, and a church overseen by Ghana’s most influential preacher. We are also engulfed in the dust of Ghana’s dry season, and an acrid cloud of smoke billows from the other side of the yam market.

The scene inside Agbogbloshie isn’t pretty and health and environmental concerns are real, but material only ends up in the scrapyard after it has been used and reused elsewhere in Ghana.

We dash across the street, avoiding impatient, angry taxis, heaving yam trucks, and two women walking with sacks of yams atop their heads, immune to the commotion. Between onion stalls, a driveway is formed by three large concrete blocks that gives way to a muddy path sloping toward the smoke. As we enter, we pass a young man pulling a wooden cart piled with six desktop computers.

“Oh yeah,” Oluu says as we walk up the path. “At first, pushing the cart was so hard for me. I’d start early in the morning and go all around Accra looking for scrap. Metal, computers – it didn’t matter. Then come here and sell.”

“Here” spreads out before us as the muddy path widens into a space that’s roughly 650 feet long and 1,450 feet wide (accounts suggesting it’s larger seem to mistake the city dump abutting it as being a part of the scrap yard). At that scale, it’s not the world’s biggest anything, much less its “biggest digital dump.” I am personally familiar with recycling facilities in China, Europe and North America that are significantly larger.

Which makes sense if one looks at the data.

According to the most recent data available, Ghana imported 215,000 metric tons of secondhand electronics in 2011. For the sake of argument, let’s say that number tripled over the next decade (unlikely, but let’s argue it), to 645,000 metric tons. Meanwhile, the UN estimates the globe generated 44.7 million metric tons of e-waste in 2016 (the most recent date for which data is available). Which, if accurate, means that Ghana’s e-waste imports accounted for no more – and likely far less – than 1.5 percent of the world’s e-waste.

Still, there’s not much pleasant at Agbogbloshie. To our right is a trash-strewn field where junk cars, vans, trucks and buses are piled up haphazardly, waiting to be torn into their individual parts for resale or recycling. That’s no accident: Agbogbloshie is mostly devoted to recycling automobiles and selling the parts. In fact, that’s been the primary business here since the early 1990s. The roughly 500 workers at Agbogbloshie (many also call it home) crowd dirt-floored stalls, mostly hammering away at greasy automobile parts, whether axles or motors. Other workers dismantle whole vehicles using hand tools. Environmental protection isn’t a concern: Oil and other fluids drain off into the soil and the nearby Korle Lagoon. Human health matters even less: Safety equipment is nonexistent, and the air is riven with the smell of burning plastic.

Of course, Agbogbloshie isn’t just cars. We walk past an empty plastic television case, a stack of 10 to 20 desktop computer cases, a pile of circuit boards, stacks of steel desktop computer cases, a small hill of rusty steel scrap, a smaller stack of still-wet paint cans, a spaghetti-tangle of burnt rubber-encrusted wire extracted from burnt tires, and three large electrical transformers (presumably from a local utility) leaking their toxic oils onto the soil. Nearby, two men pry microprocessors from circuit boards with screwdrivers and break apart aluminum window frames with hammers. Individuals who work at the site report that it recycles between 30 and 50 televisions per day.

“Is any of this junk trucked here from Tema?” I ask Oluu.

“Tema?” he asks.

“Yeah. The port. Do people bring it from Tema to dump it here?”

“Oh no. Too far,” he answers (Tema is 20 miles away). “Everything here is thrown away by people in Accra. The things in containers at Tema are too valuable for Agbogbloshie.”

“Really?”

He laughs. “When I worked here, we wanted things from Tema. That’s big money. Instead we have to scrap in the neighborhoods.”

As any Accra taxi driver will be happy to explain, Agbogbloshie is where Ghanaian things go after they’ve been used until they can’t be used or repaired (some will also tell you it’s a place where stolen property can be fenced). Most of that Agbogbloshie-bound junk was, in fact, imported into Ghana, then used, repaired, and reused, often for decades. What little data exists supports the claim: According to a survey of West Africa’s e-waste, as much as 85 percent of the used electronics in Ghana were generated in Ghana itself, from devices that were purchased new or used in Ghana or were imported as working or repairable. Computers and televisions too old for Accra make their way to smaller towns, where they last for years, even decades.

It’s not hard to find this information. It’s available online or by taking a taxi. Yet, for more than a decade, reporters have failed to ask these questions or search for these answers. Why? It’s not my place to impugn the motives of other reporters. What I do know (based on conversations with reporters) is that many reporters are sent to Agbogbloshie by editors in hope of replicating a story seen in The Guardian or on BBC. For Europeans in particular, Ghana is a short and relatively inexpensive reporting trip, and Agbogbloshie is easily accessible. Nonetheless, it’s still an investment, and few reporters – especially television reporters – are going to risk calling an editor and saying, “By the way, the BBC got it wrong. It’s actually an auto junkyard.”

Device repair specialists in Ghana help ensure that computers and TVs that that no longer appeal to residents of Accra, the capital, can continue to be used in smaller towns, where they can last for decades.

Now, to be clear: I’m not excusing anything that happens at Agbogbloshie. As someone who grew up in the recycling industry, and has covered it for years as a reporter, I can state with confidence that there’s a safer and cleaner way to do pretty much everything that’s done there. Meanwhile, what happens in Agbogbloshie has devastating consequences on the environment and human health (it’s not uncommon to hear deep hacking coughs as one walks around Agbogbloshie).

But that’s not the only lens through which one should understand Agbogbloshie. A wider lens that takes in a West Africa beyond Agbogbloshie – that incorporates Accra’s up-and-coming middle class, its countless secondhand shops, and the port of Tema – suggests hope amid the dinge. In that picture, Agbogbloshie, a slum that’s home to 40,000 people, has risen above poverty and pollution and functions as a perfectly circular economy where things are used and then reused – in effect, injected back into middle-class African life as refurbished products – in ways that rich countries simply never achieve.

You just have to look for it!

Walk out of the dump, take a right, cross the bridge, and you find businesses selling goods made from junk sold in the junkyard. There are aluminum cooking pots and stoves made from scrap aluminum; steel barbecue grills made from scrap steel or aluminum; new electrical transformers made from scrapped transformers; stall after stall of refurbished automobile parts; and businesses that repair computers and make “new” ones from parts recovered from old computers. They are the “thirdhand market,” super-low-end counterparts to the secondhand market. It’s all possible because, at some point, somebody imported used stuff from a wealthier country. That stuff circulated through Ghana, round and round, until it landed here.

“How many people were pushing carts around Accra when you were working here?” I ask Oluu.

“So many. We’d all be looking for the same thing. That’s how the computers come here. We’d buy them from businesses and homes.”

After a year of pulling carts, Oluu moved up. A cousin secured a contract with a Chinese trader interested in buying and shipping Ghanaian circuit boards back to China for recycling (the market for old boards is much stronger there than in Ghana). Oluu left his cart behind, hopped on a motorcycle, and spent his days driving around Accra buying electronics from the men with whom he used to pull carts. Oluu also picked up computers and sold them to the many repair shops around Agbogbloshie that took these machines, fixed them and resold them. If a computer couldn’t be fixed, they’d recover the parts and build a machine from those. Even today, Agbogbloshie’s jerry-rigged machines remain a popular and affordable technology for students, businesses, and, in Oluu’s words, “regular people.” Only if a part can’t be fixed (and in Ghana, skilled circuit board repair is common) is it recycled – often in China or Nigeria. Soon, Oluu was making enough money to afford an apartment of his own.

We emerge from the scrapping zone into an open space that abuts the landfill and comprises perhaps one fifth of what is known as Agbogbloshie – and 99 percent of what’s written, photographed, and broadcast about it. Trash is strewn everywhere; my feet crunch it as I walk. A few hundred feet away a group of perhaps 20 people stands around three smoky, noxious fires sending black clouds of poison across Agbogbloshie. There are two groups among them. The larger one, comprising perhaps a dozen people, are Agbogbloshie scrap workers and business owners who arrive with 10-pound balls of insulated wire extracted mostly from cars. To sell that wire for scrap, they need the insulation burned off. So they pay the smaller group here, the one that tends the fires, to do just that. Every day, a few hundred pounds of charred copper are sold out of Agbogbloshie, preceded by toxic smoke.

A small wooden shed sits roughly a hundred feet from the burning. It’s a kind of clubhouse for the burner crew, and Oluu approaches it confidently (he is a member of the same tribal group as the burn crew). Awal Mohammed, a burly leader of this group, has a family and employment opportunities in the Northern Region of Ghana, but he prefers this life. He’s the boss and – to be honest – I think he enjoys the attention he receives as the face (literally) of Agbogbloshie. When photographers visit the site, he’s the one whose photo is often taken next to the flames (if you’ve ever seen a photo of an African man burning wire, the odds are good it’s Awal). If a photographer tips him properly, he’ll add a bit of extra fuel to the fire to make it more photogenic, put his safety at risk and wave a burning tire over his head, or, at a minimum, ensure his crew of burners is available. These are all services provided to the producers of a 2017 video for the British rock band Placebo, who certainly got what they paid for. Placebo promoted the video on social media as being “filmed on location at Agbogbloshie, the world’s largest e-waste dump.”

This text was excerpted from “Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale” by Adam Minter. It will be available Nov. 12, 2019 from Bloomsbury. Used with permission.